10 Ostraka and Graffiti

This is an online digital edition from ISAW Digital Monographs. The print edition of this work can be consulted at https://isaw.nyu.edu/publications/isaw-monographs/ain-el-gedida

10.1 Introduction

The ostraka uncovered at ʿAin el-Gedida in 2006–2008 fall into the common categories represented in this type of texts: a short letter (1), accounts (2-3), lists (4) and receipts (5-9). Texts on three of the ostraka (10-12) were classified as uncertain because of their fragmentary or laconic nature. Ten were written in Greek and two in Coptic.

Eleven out of twelve ostraka are dated to the fourth century, either on palaeographic and internal grounds or based on their archaeological context. One ostrakon (9, see comm. l. 1) is assigned to the third century because of the monetary value of rent mentioned in the text. The ostrakon’s early dating is in agreement with the chronology of its context, as it appears to belong to the phase when the building where it was found was a temple, possibly dated to the second–third century (see Section 6.5 and Section 6.7). Undated ostraka from surface clearance or unreliable contexts (1, 3, 10, 12) were assigned to the fourth century both on palaeographic grounds and because the bulk of the pottery and coins recovered from ʿAin el-Gedida (Chapter 8 and Chapter 9) indicate that the site was occupied in that century. Moreover, the Coptic texts are very unlikely to date before the fourth century, and there are some reasons to think that 1 might be later. The absence of any other material datable later than the late fourth or early fifth century at the site, however, leads us to prefer an earlier date to that chronological zone, which is also consistent with the general horizon of the latest ostraka at Kellis and Trimithis. Ostraka from secure contexts were dated more precisely on the basis of numismatic evidence (4, 8, 11) and their chronology is discussed in greater detail below.

Four documents (2, 5, 6, 7), three of which come from the same building, carry indiction dates. Given the practice recorded at other sites in the Dakhla Oasis (see discussion in O.Trim. 1, Introduction), it is reasonable to place them in the second half of the fourth century. At nearby Kellis we have no secure evidence for the use of the indiction cycle before the middle of the fourth century. In addition, the apparent continued use of regnal years up to the reign of Constantius in Trimithis ostraka seems to confirm the generally late arrival of indiction reckoning in the Dakhla Oasis. If the impression from the Kellis material is not misleading, and if ʿAin el-Gedida followed Kellis in this practice, then the years mentioned in these four documents fall in the second half of the fourth century.

2, 6, and 7, discovered in two different rooms of one building complex, may be chronologically related to one another. The 12th and 13th indictions (353/4 and 354/5, 368/9 and 369/370, or 383/4 and 384/5) appear in no. 2, found in room B3, and the 11th indiction (352/3, 367/8 or 382/3) is attested in no. 7 from room B1 of the same complex. These two ostraka were found in layers of occupational/ post-occupational debris directly above floor levels (2: room B3, DSU10; 7: room B1, DSU14). 6, in turn, was embedded in the plaster of a niche in room B1, which may be later than the wall this niche was in, but certainly not post-occupation. The second indiction mentioned in this document likely corresponds to 358/9, 373/4 or 388/9. Therefore, given the context and the relatively short life span of this type of document, it is possible that the three ostraka refer to years of the same indiction cycle. The find patterns at Kellis and Trimithis on the whole lead us to think the indiction cycle of 357–372 is the most likely choice.

No. 5, found in Room B4, also mentions the 13th indiction (354/5 or 369/370; the earlier possible but less probable dates are 324/5 and 339/40), but it need not be the same year as in 2, since B4 was not part of the same complex.

Place names mentioned in the ostraka are few but worthy of note. One toponym that deserves to be discussed is found in 9, a receipt issued to a Paulos son of Mersis from the georgion of Pmoun Berri (for georgion, see comm. ad loc., l. 3). Pmoun Berri, which stems from Coptic ⲃⲣⲣⲉ (new, young), means ‘New Well’. The toponym is attested in P.Kellis 1 G 5.12 (there spelled Βερι), in O.Trim. 114, and in an unpublished ostrakon from ʿAin es-Sabil found in 2009. However, given the meaning of the name and the hydrology of the region, there may well have been more than one locality with this name in the Dakhla Oasis.1 Since the modern Arabic name of the site has essentially the same meaning, one is tempted to identify ʿAin el-Gedida as the georgion of Pmoun Berri. Nonetheless, it also cannot be entirely excluded that the settlement mentioned in the text was located somewhere else. Therefore, the hypothesis that modern ʿAin el-Gedida is an ancient site called Pmoun Berri is likely to be true, although it awaits confirmation in new evidence.

Other topographic references in the ʿAin el-Gedida ostraka concern Mothis. This is not surprising, as it was the main urban center and, from the beginning of the fourth century, the capital of the nome the settlement was part of. In 2, the account of wheat and must, Mothis is the destination of a part of the produce. 5 is a receipt for annona for the imperial estate of Mothis. Kellis, the closest town, is not mentioned directly in the documents but seems to be connected to ʿAin el-Gedida in a number of ways. The wording, formulas and onomastics in accounts and receipts from ʿAin el-Gedida find numerous parallels in the material from Kellis. For instance, 2 resembles the Kellis Account Book in phrasing and composition. The accounting of this text is also very similar to that found in other Kellis documents. The mentions of amounts going “to the house” (εἰς τὴν οἰκίαν) and “to the camp” (εἰς τὰ κάστρα), the appearance of dapanê, payment of salary, and the concept of a balance with the writer (λοιπὲ παρ᾽ ἐμοί) all point to the likelihood that he was another of the estate managers, pronoêtai, who were responsible for the Kellis Account Book (see KAB pp. 70–72) and many other documents from Kellis and Trimithis. What is more, some individuals mentioned in the ostraka are attested at Kellis (see esp. 4).

The ʿAin el-Gedida ostraka are mostly concerned with agricultural and fiscal issues and their subject matter and vocabulary are consistent with that of textual evidence from other sites in the Great Oasis. The foodstuffs mentioned are wheat, barley, and must, commodities are transported on donkeys, and rents are paid in money and chickens. The measures used are consistent with the ones in documentation from other sites in the Dakhla Oasis and discussed most thoroughly in the KAB (pp. 47–51).

The documentary evidence shows that ʿAin el-Gedida was a village or hamlet in the Mothite nome that functioned as a satellite of the larger town of Kellis and was associated with it, and likely with other epoikia surrounding it, through ties of land ownership and tenancy, as well as personal relations. The texts show an agricultural community likely tied to a large estate like the one that produced the KAB. However, at this point it is difficult to say if ʿAin el-Gedida was property of a single individual.

A less prominent but recurring theme in the ostraka is the Dakhla garrison. In 2, a part of the produce is sent to “the camp,” presumably the principal base of the military unit described in the Notitia Dignitatum (Or. XXXI, 56 [Seeck, p. 65]) as the Ala I Quadorum placed at Trimithis (erroneously assigned to the Small Oasis in the ND). The camp was in fact at El-Qasr, a few kilometers north of Trimithis, as discoveries by Fred Leemhuis since the 2005–2006 season have shown (see also KAB, p. 73, and O.Kellis 102.5n).2 The oldest part of El-Qasr is laid out in a fashion strongly reminiscent of a Roman camp, and the investigation of an old well by the Dakhleh Oasis Project in 1980 led to the discovery of signs of Roman occupation. In addition, investigation of this early phase of the site by F. Leemhuis and by the Supreme Council of Antiquities, conducted since 2005, have revealed standing remains of massive Roman brickwork structures, which are to be associated with this camp.3 The site also yielded Coptic ostraka referring to the imperial kastron that had since become a settlement governed by headmen.4 Further references to the camp and its garrison are found in ostraka from Trimithis. O.Trim. 1.73 refers to an ala (εἴλη) and its decurion (δεκαδάρχης). In the ʿAin el-Gedida material, the praepositus attested in 8 is likely an officer of this unit or of another detachment serving in the Oasis. 5, a receipt for annona, indicates that a detachment of the ala was on duty in Mothis. In the same text, the soldiers who are the recipients of the collected barley are referred to for the first time as horse-archers.

Lastly, the Coptic letter 1 mentions apa Alexandros and apa Kire, who were most likely members of a monastic community (see comm. l.1). A monastery is mentioned several times in the material from Kellis. The KAB lists a top(os) Mani (KAB ll. 320 and 513), interpreted as a Manichaean monastery,5 as a tenant of the estate and a certain Petros the monachos paying amounts of dates and olives on its behalf (KAB ll. 975-6, 1109, 1433). Another monachos, Timotheos, is an intermediary for a certain Nos paying turnips (ll. 1080). A monastery is mentioned in P.Kellis. 5 C. 12.6 (also see P.Kellis 1 G. 12.18–19) from ca. 360–365 and another monk, Psais, is attested in O.Kellis 121.5. The modern village of Tineida (perhaps derived from Copt. ⲧϩⲉⲛⲉⲉⲧⲉ, “monastery”) is considered a candidate for an ancient monastic site. It has also been suggested that modern el-Hindaw, located to the west of ʿAin el-Gedida, may represent Coptic ⲛⲧⲟⲟⲩ (“the monastery”).6

10.2 Technical Remarks

The headers in the catalogue of ostraka below are consistent with those of O.Trim. In addition to characterizing the physical appearance of the sherds, they supply the following contextual information: inventory number (Inv.), area (A or B), room, stratigraphic unit (DSU or FSU), field number (FN), and fabric code.

The inventory number is a unique number in a sequence given to all objects found on the site. Inventory numbers 4, 7–10, 17, 25 and 28 were excavated in the 2006 season, number 529 comes from the 2007 season, and 660, 830, and 1007 from 2008. Ostraka found in area A were recovered during surface clearance and did not come from a sound stratigraphy (see Section 1.5 in this volume for the division into areas A and B). In area B, ostraka were uncovered in archaeological contexts described in Section 2.3, Section 3.1.1, Section 4.2, Chapter 6. The context is discussed in greater detail only where it is relevant to the dating of the texts. The abbreviation DSU stands for Deposition Stratigraphic Unit and FSU is Feature Stratigraphic Unit (see Section 1.5); field object numbers (FN) are numbers assigned in the field (starting from 1 each season) in order to document the location of objects in situ. Ostraka discovered in sieving in area B and in surface clearance in area A do not have field object numbers. The fabric codes are explained in Chapter 8.

The texts are presented according to the standard papyrological practice. The use of symbols is consistent with the Leiden Convention:

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| ( ) | Resolution of an abbreviation or symbol |

| [ ] | Lacuna in the text |

| [[ ]] | Letters cancelled by the scribe |

| αβγδε | Letters the reading of which is uncertain |

| . . . . . | Letters of which part or all remain but are illegible |

| [ ± 5 ] | Approximate number of letters lost in a lacuna and not restored |

Abbreviations are resolved in the text. Line notes indicate the form used in the text and correct non-standard Greek except in the case of personal names. Egyptian proper names without terminations (i.e., undeclined or not hellenized) are not accented. Greek names and words written in a non-standard spelling are accented as if the correct form had been written. In translations, Greek and Egyptian names are transliterated directly, while Roman names are given in Latin form.

10.3 Ostraka

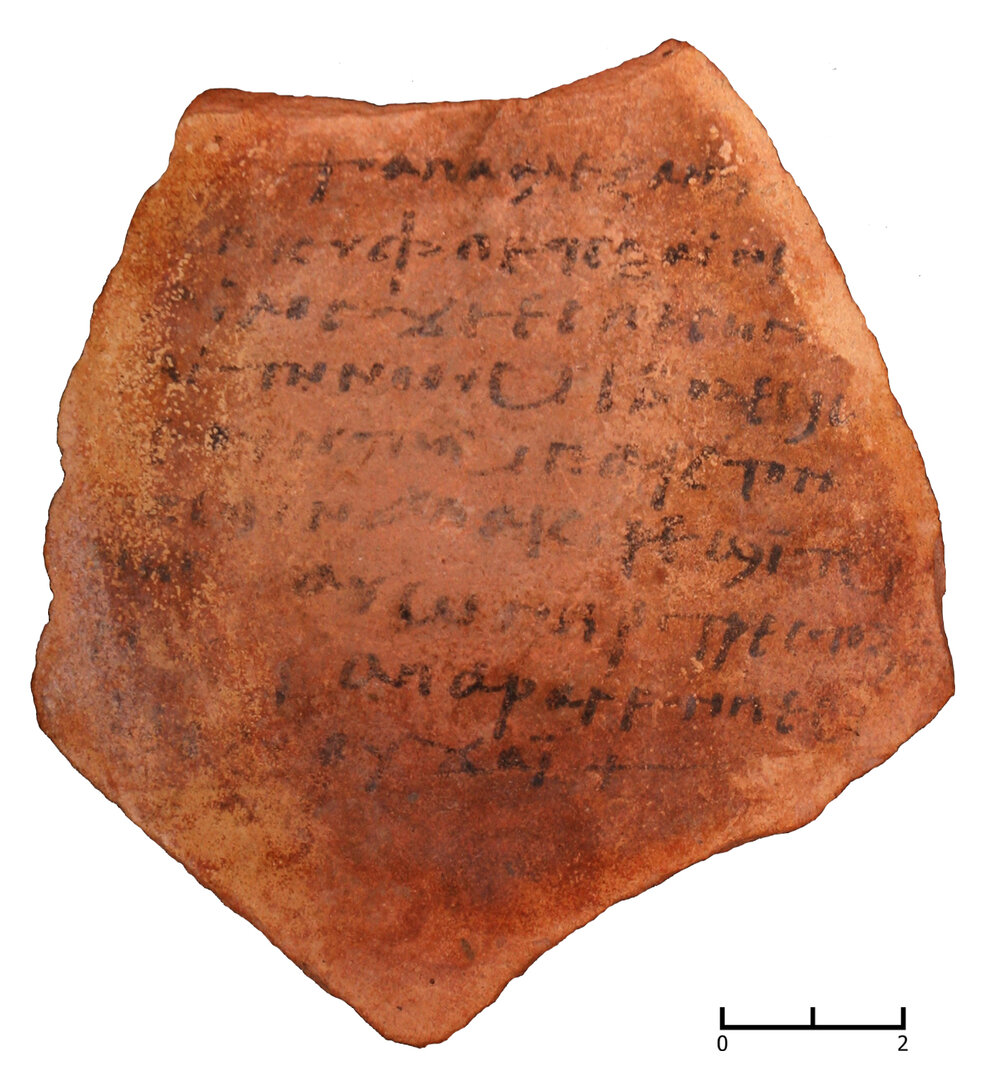

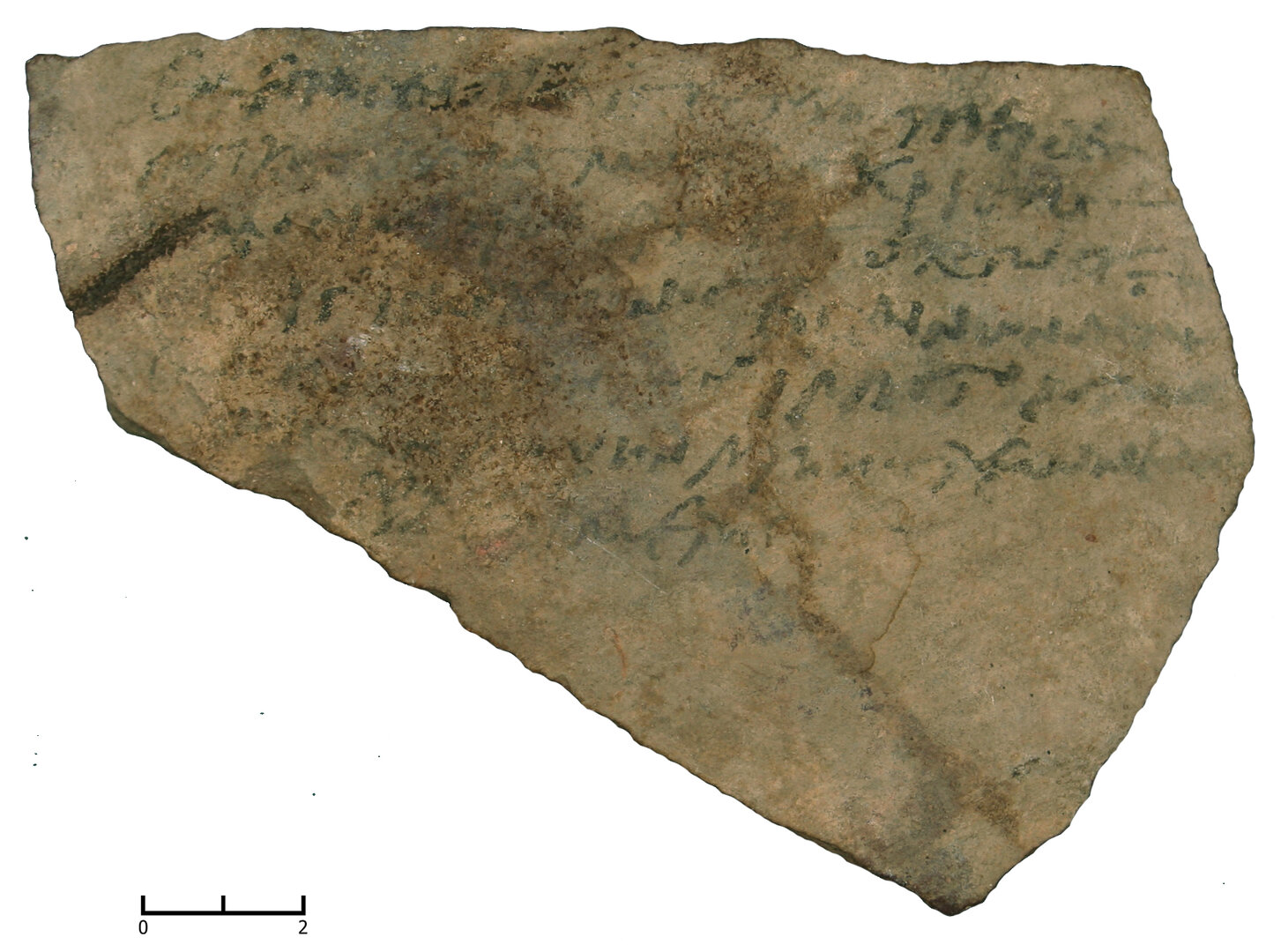

1. A letter concerning pakton.7 Second half of the fourth century? (Plate 10.1)

Inv. 4. Area B, room B4, DSU4 (surface).

10.3 x 9.8 cm; complete but faded in places. Text on convex side.

Fabric: coarse A11 with exterior cream slip.

The dating of this Coptic letter requires a commentary. Both the onomastics and the mention of pakton point to a date later than the rest of the assemblage. The names Pesente and Kire are not attested until the sixth century (see commentary below) and the term pakton appears for the first time in SB 3.6266 dated to 538 CE. The language of the document also sets it apart, as the great majority of fourth century texts found so far at ʿAin el-Gedida are in Greek. Since the ostrakon is a surface find, it could be later than the abandonment of the site. Nonetheless, given the absence of other much later surface finds, we are reluctant to date it outside the chronological range that we have at the site. The recovered ceramics date from fourth and early fifth century at the latest, which is consistent with the range of hands evidenced by the ostraka. The palaeography of this text can be dated to the late fourth century based on comparanda from Kellis. In addition, both the hand and the opening formula of the letter find parallels in two ostraka found in El-Qasr and dated by Iain Gardner to the late fourth-early fifth century.8

| † ⲁⲡⲁ Ⲁⲗⲉⲝⲁⲛⲇ̣ⲣ̣[ⲟⲥ] | |

| ⲡⲕⲩⲫ(ⲁⲗⲁϊⲟⲧⲏⲥ) ⲡⲉⲧⲥϩⲁϊ ⲛ . [ ] | |

| ⲗ̣ϊⲗⲟⲥ ϫⲉ ⲉⲥ ⲡⲉⲥⲏⲛ[ⲧⲉ] | |

| 4 | ⲁϊⲧⲛⲛⲟⲟⲩϥ ⲉⲃⲟⲗ ⲉϣⲱ̣ |

| ⲡ̣ⲉ ⲟⲩⲛⲧⲏϥⲡⲁⲕⲧⲟⲛ | |

| . .ϣϊⲛ ⲁⲡⲁ Ⲕϊⲣⲉ ϣϊⲧϥ | |

| ⲛ̣ⲏϥ ⲁⲩⲱ ⲙⲡ̣ⲣⲧⲣⲉⲥⲧⲟⲝⲉ̣ | |

| 8 | ⲛⲏ̣ϥ ⲁⲡⲁⲣⲁⲅⲉ ⲙⲙⲉϥ |

| . . . .ⲟⲩϫⲁϊ † |

“It is apa Alexandros the foreman (κεφαλαιωτής) who writes to --lilos (or --ailos): As for Pesente, I sent him away. If he has rent (πάκτον) … , apa Kire demands/asks for it. And let it not seem appropriate to him to trouble him. Farewell (?).”

1 See Derda and Wipszycka 1994. The title Apa does not in itself help to distinguish between ordinary clergy and monastics, but if the date is indeed the fourth century the latter seems more likely. It is interesting that an Alexandros appears in one of the ostraka from the Kellis West Church (O.Kellis 121.6), one line below a Ψάις μονοχ(ός), which the editor takes to be most likely a misspelling of μοναχ(ός). For references to a monastery in the proximity of ʿAin el-Gedida, see Introduction.

2 ⲡⲕⲩⲫ is presumably the abbreviation of the article plus a Greek word, given the use of phi. No word starting in κυφ- seems plausible, but a small group of ostraka found in excavations by the wall of the Roman fort at El-Qasr by the Supreme Council of Antiquities includes one written by Ⲡⲁϩⲁⲙ ⲡⲕⲩⲫ( ) and another by Ⲡⲁϩⲁⲙ ⲡⲕⲉⲫⲁⲗ( ), showing that upsilon has interchanged with epsilon (see Gardner 2012: 471 and 473). The resolution κεφ(αλαιωτής) thus appears inescapable. The combination of this title with a clerical title, Apa, is remarkable. An Apa Sion is kephalaiotes of dyers in Herakleopolis in SB 16.12717.5, 31-32 (dated 640–650), and an Apa Ol (if it is not the name Apaol) is kephalaiotes in SPP 8.749.4.

2–3 The nu at the end of l.2 is likely the preposition ⲛ- introducing the direct object (see opening formula type II, Biedenkopf-Ziehner 1983: 226). The long vertical stroke may belong to a rho or a kappa. No name ending with -lilos or -ailos can be found in Hasitzka’s Koptische Namenbuch and a TM search yields some improbable -ailos names (Σκαίλος, Καίλος, Ισμαιλος, Δαλάιλος). One would consider Λίλος, a variant of Λιλοῦς (a name attested in Kellis, O.Kellis 270.2, P.Kellis 1 G. 47.1), but its attested Coptic counterparts are ⲗⲓⲗⲟⲩ and ⲗⲉⲗⲟⲩ. Ailos would be an unlikely variant of the Latin name Aelius (all Greek variants retain the iota after the lambda) and it is thus far unattested in Coptic texts. Moreover, it would leave us without an explanation of the last letter (and any lost) in the previous line.

It is a natural supposition that the recipient was at ʿAin el-Gedida, but this need not be the case.

3 Pesente appears in many spellings in the ancient texts, including Πεσύνθιος or Πεσύντιος. The name is not attested in securely dated documents as early as the fourth century. Πεσύνθιος is featured in BGU 2.668ro.12 (Western Thebes), broadly dated to the fourth to seventh centuries. The Coptic spellings are attested in documents dated to the sixth-eighth century (Theban texts KSB 3.1332.2; P.Lond 4.1419 (Greek); O.Medin.HabuCopt 46; O.Theb.Copt 31), with the exception of ⲡⲉⲥⲛⲧⲉ found in P.Mich.Copt 6.1, the dating of which spans from the fourth to the sixth centuries. However, a Πεσόνθις is attested on a mummy label dated as early as the second-third centuries (T.Mom.Louvre 973).

5 If, as the context would suggest, this ostrakon is to be dated to the fourth century, it may be the earliest known reference to πάκτον in a Greek or Coptic document. Greek references do not occur until the sixth century (SB 3.6266, of 538; P.Lond 5.1727, of 583/4). The Coptic references in Förster, Wörterbuch 601-02, do not include any before the seventh century, although many are undated or only approximately dated. For the meaning of the term, see most recently Wegner 2016: 191–92.

6 The first word of the line could be referring to the pakton as genitive or attribute, in which case one would need a nu as the first letter. However, we have not been able to find any appropriate word in the reverse dictionary of Coptic (M-.O. Strasbach, B. Barc, Dictionnaire inversé du copte, Louvain 1983). The only noun ending with ϣⲓⲛ is ⲁⲣϣⲓⲛ, “lentil”, but the letter before shai cannot in any case be a rho. Alternatively, the word could be connected to the following noun phrase as a conjugation base, but we do not know any form ending with ϣⲓⲛ.

The name Ⲕⲓⲣⲉ and other Coptic variants are unattested prior to the sixth century, but the Greek name Κῦρος appears over 30 times in fourth-century documents, including several ostraka and inscriptions from the Western Desert (O.Waqfa 66.7; O.Douch 3.222.2 and 346.2; SB 20.14799.2 [Shams ed-Din]; SB 20.14850.1 and 20.14853.1 [Bagawat]). Since variants of the name Kyros contain the morpheme “apa” (Derda and Wipszycka 1994: 53), the reading ⲁⲡⲁⲕⲓⲣⲉ is also a possibility. However, Kire’s appearance in the same context as apa Alexandros may indicate that he too represented an ecclesiastical institution. Possibly apa Kire, whom Pesente was not supposed to trouble, was a monastic superior and the letter concerned rent on monastic property. The addressee of the letter may have interceded on behalf of Pesente.

7 ⲛⲏϥ (Sahidic ⲛⲁϥ) should be treated here most probably as a dativus ethicus.

The letter mu after ⲁⲩⲱ gives a negative jussive here.

ⲧⲟⲝⲉ is the Greek δοκέω, meaning “zweckmässig erscheinen, einsichtig sein,” see Förster, Wörterbuch pp. 206-207, with citations of analogous phrases in P.Lond.Copt. 1.479.v.3 (ⲛⲡⲣⲧⲉⲥⲇⲟⲝⲏ ⲛⲁⲕ) and 1.1175.3 (ⲙⲡⲣⲧⲣⲉⲥⲇⲟⲝⲏ ⲛⲁⲕ ⲉⲧⲓ ⲛⲉϭⲁⲙⲟⲩⲗ ⲛⲕⲉⲗⲁⲁⲩ).

8–9 The text at the start of these lines is extremely faded.

8 ⲁⲡⲁⲣⲁⲅⲉ for the Sahidic ⲉ-ⲡⲁⲣⲁⲅⲉ. ⲙⲙⲉϥ (Sahidic ⲙⲙⲁϥ) introduces a direct object.

9 ⲟⲩϫⲁϊ (literally “health”) seems to be an abbreviated standard epistolary formula ⲟⲩϫⲁⲓ ϩⲙ ⲡϫⲟⲉⲓⲥ, “Farewell”.

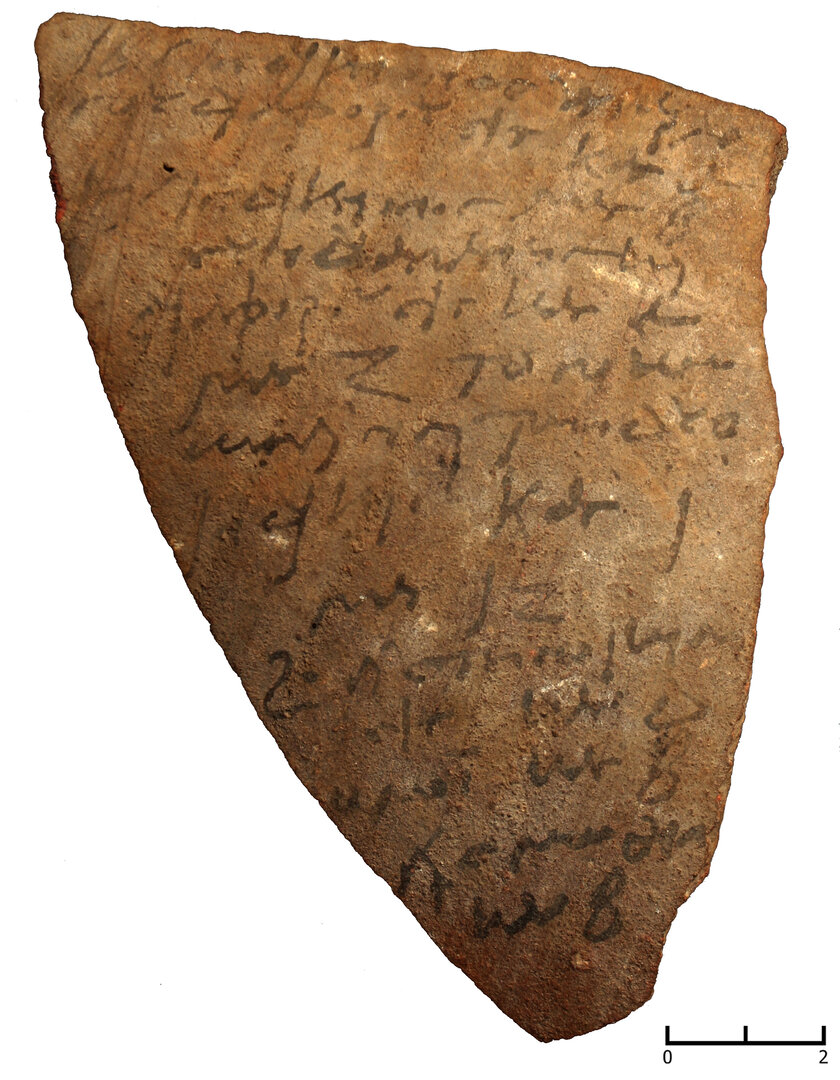

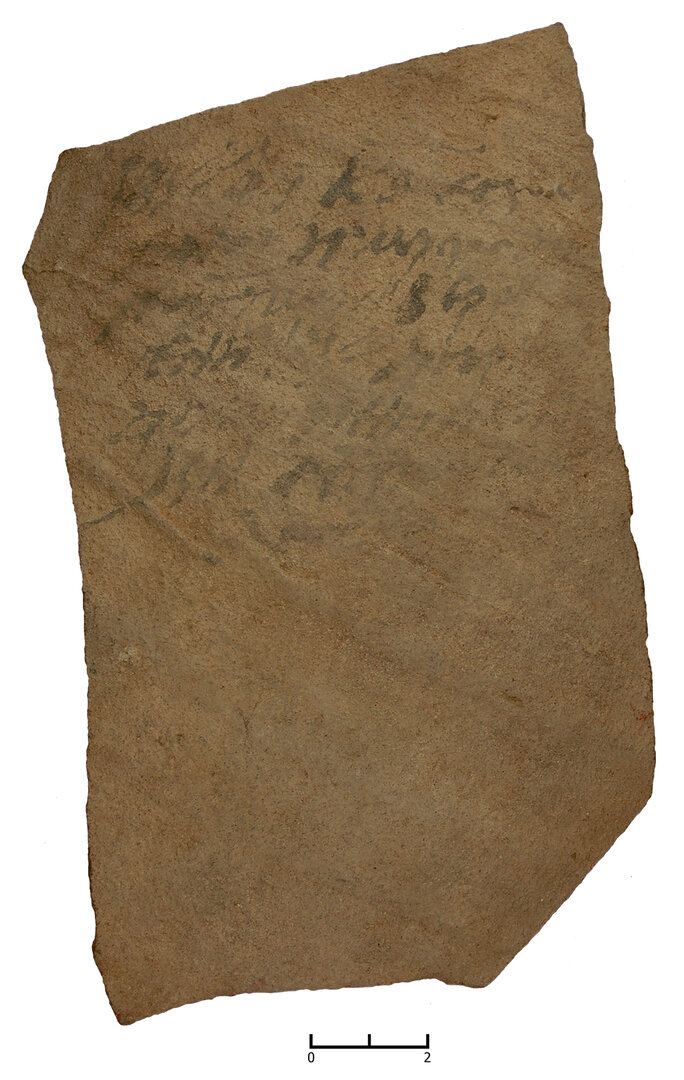

2. Account of wheat and must. 354/5, 369/70, or 384/5. (Plate 10.2)

Inv. 7. Area B, room B3, DSU10.

9.5 x 13.2 cm; complete. Text on both sides, oblique to the wheel-marks.

Fabric: A1a with exterior cream slip.

Convex side

| ιβS/ ἰνδικτίονος ὑπὲρ λό- | “12th indiction, on account | |

| γου διαφόρου σίτ(ου) κάγ(κελλος) α | of interest, 1 cancellus (art.) of wheat. | |

| ιγ/ ἰνδικτίονος μάτ(ια) β | 13th indiction, 2 matia | |

| 4 | σὺν δαπάνης καὶ | including expense, and |

| διαφόρου σίτ(ου) κάγ(κελλοι) ε | for interest, 5 cancelli of wheat, | |

| μάτ(ια) ζ τοπικῷ | 7 matia by the local measure. | |

| ὥστ’ εἶναι τῶν δύο | Total of the two | |

| 8 | ἰνδικτιόν(ων) κάγ(κελλοι) ϊ | indictions, 10 cancelli, |

| μάτ(ια) ιζ. | 17 matia. | |

| (ὧν) εἰς τὴν οἰκίαν | From which: to the house | |

| σίτ(ου) κάγ(κελλοι) δ | 4 cancelli of wheat. | |

| 12 | ὁμοί(ως) κάγ(κελλοι) β | Likewise, 2 cancelli. |

| εἰς Μῶθιν | To Mothis, | |

| κάγ(κελλοι) β | 2 cancelli. |

Concave side

| εἰς τὰ κάστρα κάγ(κελλοι) δ | To the camp, 4 cancelli. | |

| 16 | γί(νονται) ὁμοῦ κάγ(κελλοι) ιβ | Total altogether, 12 cancelli. |

| (ὧν) ἔσχεν καγ(κέλλους) ια μάτ(ια) | Out of which he got 11 canc., 5 matia; left | |

| ε λοιπὲ παρ’ ἐμοὶ σίτ(ου) | in my hands, of wheat | |

| τοπικῷ μάτ(ια) ιθ | 19 matia by local standard. | |

| 20 | ὑπὲρ γλεύκ(ους) κερ(άμια) ϛ | For must, 6 keramia. |

| λοιπὲ γλεύκ(ους) κερ(άμια) ε | Balance of must, 5 keramia. | |

| ει . . . . | To Mothis (?).” |

| 2 σιτ καγ’ | 3 ματ’ | 4 l. δαπάνῃ δ ex δι | 5 σιτ καγ’ | 6 ματ’ |

| 8 ινδικτιον καγ’ | 9 ματ’ 10 Ϩ· | 11 σιτ καγ’ | 12 ομοī καγ’ | 14 καγ |

| 15 καγ’ | 16 γι/ καγ’ | 17 Ϩ· καγ’ ματ’ ε ex ζ | 18 l. λοιπὰ σιτ | |

| 19 ματ’ | 20 γλευκ κερ’ | 21 γλευκ κερ’ |

2, 5 λόγου διαφόρου: See P.Harr. 1.86.5, where it is clearly a monthly interest rate on a loan. The figure presumably represents income to the writer’s employer from a loan in wheat.

4 There may be additional traces at the start, probably washed out. For δαπάνη which refers to expenditures for services by estate staff, see KAB, pp. 32–35.

6 Sc. μέτρῳ. For the “local” measure, see most recently O.Kellis 93.3n. with bibliography.

8 The amounts in lines 1-7 total to only 6 cancelli, 9 matia, not the 10 cancelli, 17 matia given in lines 8–9, let alone the 11 cancelli, 5 matia stated below (see note to line 16). One must apparently suppose another ostrakon on which additional amounts were listed.

15 For “the camp,” see KAB, p. 73, and O.Kellis 102.5n. The reference is presumably to the principal base of the unit at Trimithis (see Introduction).

16 This line is the total of lines 10 to 15. A total of 12 cancelli had been sent to various destinations, even though “he” (as is explained in lines 17–19) received only 11 cancelli, 5 matia, leaving the writer with a balance on hand of 19 matia. The standard used is the expenditure mation, here called the local measure, of 23 or (here) 24 matia per artaba; see KAB, pp. 47–48. The account suggests, however, that the writer was starting with the receipts totalled in lines 8–9, or 10 cancelli, 17 matia, which is 12 matia less than the figure he cites later.

17 The third person singular may refer to the landlord, who got the credit for the amount because of the deliveries. Although it is not impossible that we should correct to ἔσΧον (first person singular), the fragmentary character of the account makes such corrections hazardous.

18 The phrase λοιπε παρ’ ἐμοί, meaning “in my hands”, seems to imply that the remaining 19 matia still need to be paid or delivered. For the spelling λοιπὲ see, e.g., O.Kellis 143r.5.

22 εἰς Μῶθ(ιν) is possible, but only the faintest traces of the last four letters are preserved.

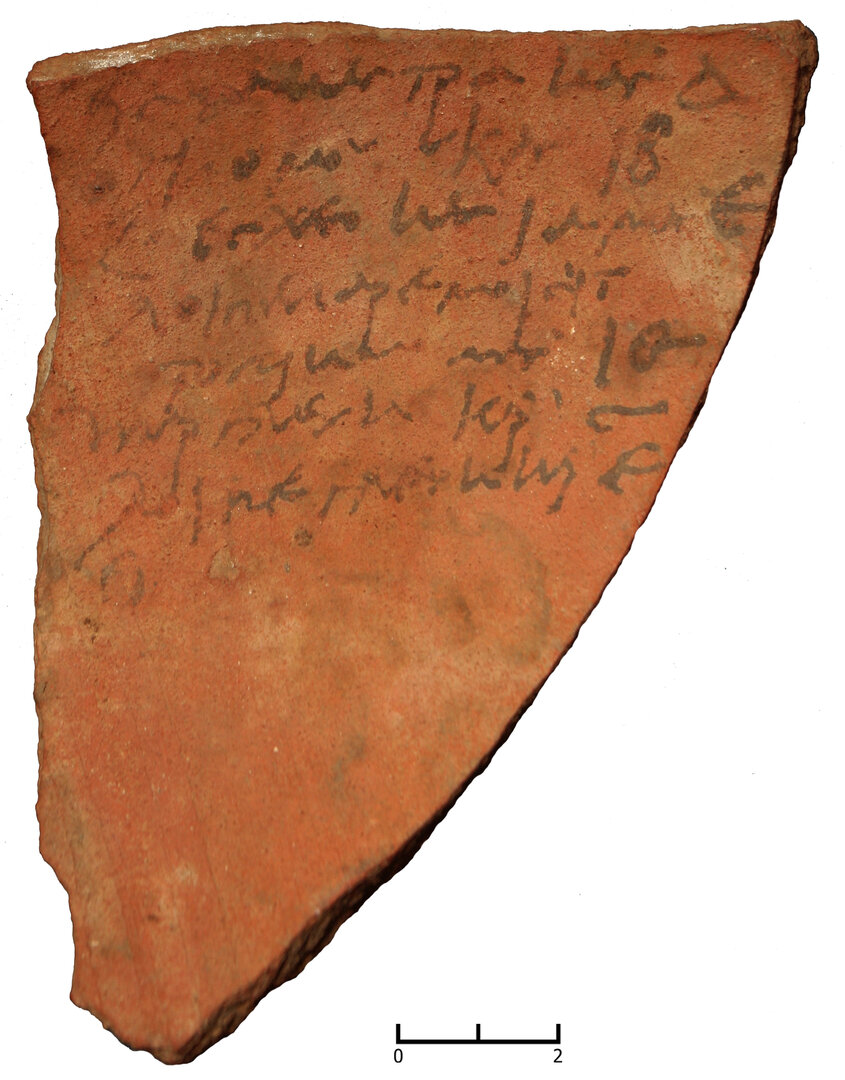

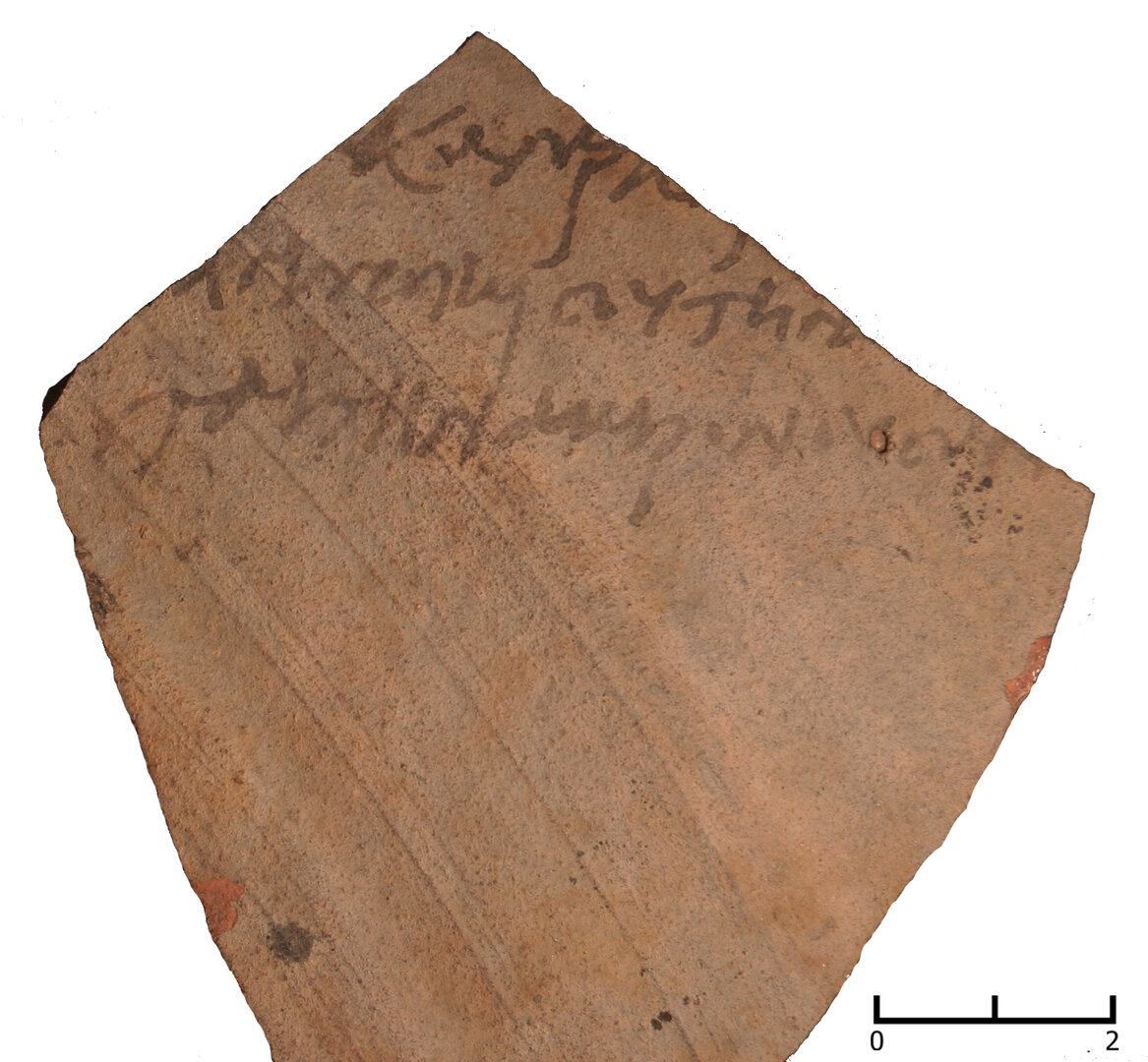

3. Account of donkeyloads. Fourth century. (Plate 10.3)

Inv. 10. Area A, room A25, clearance.

7.5 x 7.4 cm; complete? Text on convex side.

Fabric: B10.

Traces of what appears to be ink on the upper edge (above the omicron in Δείου) may indicate that the text was originally longer and we are left with its last four lines. The beginning of the first two lines and the middle of the fourth line are almost completely faded and only traces are visible. Most of the names are read with doubts. The way the words are spaced out in the lines looks as if the scribe had written the number of donkeyloads in each line prior to putting down the names.

| Τιθοῆς Ψάιτ(ος) Δείου κτῆ(νος) α | |

| Π◌̣◌̣ις Βησᾶτ(ος) κτῆ(νος) α | |

| Ψύρος Πεθεῦτ(ος) κτῆ(νος) α | |

| 4 | Πτολᾶς [ ± 4 ] κτῆ(νος) α |

| 1 ψαιτ | κτη/ | 2 βησατ κτη/ | 3 πεθευτ κτη/ | 4 l. Πτολλᾶς κτη/ |

“Tithoes son of Psais, grandson of Deios, 1 donkeyload; P--is son of Besas, 1 donkeyload; Psyros son of Petheus, 1 donkeyload; Ptolas son of --, 1 donkeyload.”

Each line gives a name and patronymic followed by the abbreviation HTL( ), to be expanded as κτῆ(νος), and the number 1. A somewhat more informative account of donkeyloads can be found in O.Kellis 102 (and cf. 103), where κτῆ(νος) should be rendered as “donkey” throughout. Camels in the ostraka from the Oasis are always specifically designated as such. It seems unlikely that the account refers to the delivery of donkeys themselves, but rather to donkeyloads of some goods known to the writer but not mentioned here.

1 Tithoes son of Psais is a common enough combination of names to justify adding a grandfather’s name. Deios is frequent, but not attested in the Oasis.

2 The name is illegible.

3 Psyros is a rare name found in the Oasis (only P.Kellis 1 G. 33.1, but two letters uncertain). Syros, however, is fairly common.

4 Ptollas, normally spelled with two lambdas, is not uncommon, but thus far absent from the Western Desert.

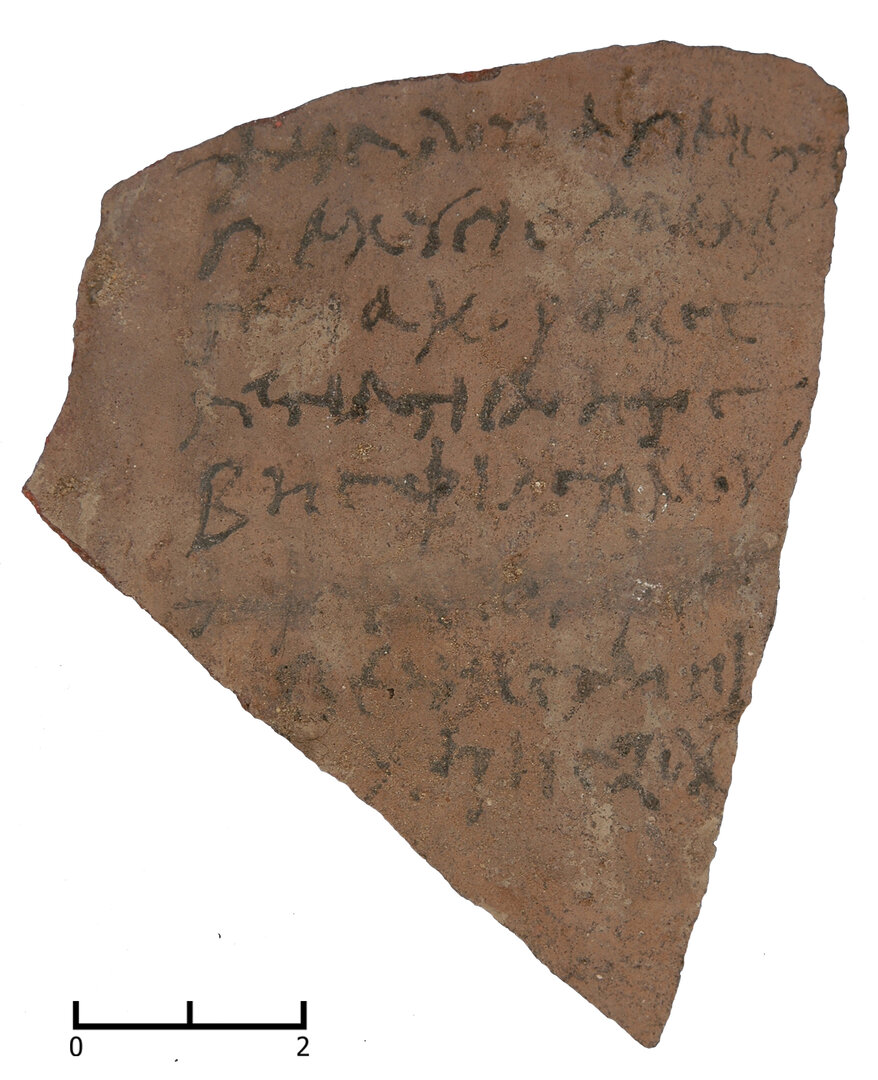

4. List of names. Second half of fourth century. (Plate 10.4).

Inv. 1007. Area B, room B19, DSU165.

6.5 x 8.3 cm; complete. Text on convex side.

Fabric: A1b.

| Ψάις Λουια Πεκύ(σιος) | |

| Πεκῦσις ἀδελφ(ός) | |

| Γενα Κόρακος | |

| 4 | Γενα Τιθοῆτος |

| Βῆς Φιλοτίμου | |

| [[Ψάις Ἀνούφιος ]] | |

| Βελλῆς Ληπ( ) | |

| 8 | Χάρης Ζα( ) |

| 1 πεκυ/ | 2 αδελφ/ | 7 ληπ/ | 8 ζα/ |

“Psais son of Louia grandson of Pekysis; Pekysis, brother; Gena son of Korax; Gena son of Tithoes; Bes son of Philotimos; Psais son of Anouphis; Belles son of Lep--; Chares son of Za--.”

There is a striking coincidence between the names in this list and those found in the ostraka excavated in the West Church at Kellis, especially the group of accounts in money and in kind in O.Kellis 109–122. See the following notes for details. Although many of the names are commonplace, this cannot be said of Philotimos (line 5). On the basis of the numbers of talents in some of these texts, this group is certainly to be dated after the Constantian monetary reform of ca. 353 and probably in the third quarter of the century. This dating is consistent with the ostrakon’s archaeological context. The stratigraphic unit is a vault collapse with some dumped material, so it could have been used as a chinking sherd (pre-construction) or (more likely) discarded together with some occupational refuse. It seems to be related to the pottery workshop phase, which is the later of the two phases distinguished in room B19 (see Section 6.3 and Section 6.7).

1 Ψάις Λουια Πεκύ(σιος): see O.Kellis 113.

2 Πεκῦσις ἀδελφ(ός): cf. possibly KAB 1128.

3 Γενα Κόρακος: see O.Kellis 114, 282.

5 Βῆς Φιλοτίμου: see O.Kellis 110, 115.

7 Βελλῆς: see O.Kellis 115, 117, 118, and 119.8; Ληπ( ): see Ληπι( ) in O.Kellis 137.7 and ⲗⲉⲡⲟⲣⲓⲟⲥ in P.Kellis 5 C. 43. Λην( ) seems less probable and yields no satisfying parallels.

6 Ψάις Ἀνούφιος is attested in KAB 578, 1100 and 1158.

8 Χάρης O.Kellis 113; Ζα( ): possible abbreviation of Ζακαῶνος: KAB 148–9, 336, 1098; O.Kellis 115.1; 282.1.

5. Receipt for annona. 354/5 or 369/370. (Plate 10.5).

Inv. 9; Area B, room B4, DSU15 (dump layer).

14.1 x 10.2 cm; complete. Text on convex side.

Fabric: A1b with exterior cream slip.

| Ἐμέτρησεν ἀρτ(άβας) η ϊγ (ἰνδικτίονος) Εὐτύχης ὑπὲρ δεσ- | |

| ποτικῆς φυτϊας Μώθεως κριθῆς | |

| δημοσί(ῳ) μέτρῳ ἀρτάβας ὀκτώ, (γίνονται) (ἀρτάβαι) η | |

| 4 | [τ]ῆς ιγ ἰνδικτίονος εἰς ἀννῶναν τῶν |

| ἐν Μώθι ἀγγαρευόντων ἱπποτοξοτῶν. | |

| ἔγραψα τὴν ἀποχὴν Αὐρήλιος Λεωνίδας | |

| ἄρξ(ας) ἐπιμελητής. |

| 1 αρτ ϊγS | 2 οὐσϊας | 3 δημοσι γι/ ⨪ | 4 ϊνδικτιονος | 5 ϊπποτοξοτων | 7 αρξ/ |

“Eutyches paid 8 art., 13th ind. for the imperial estate of Mothis, eight artabas of barley by public measure, total, 8 art., for the 13th indiction for the annona of the horsearchers on duty at Mothis (?). I, Aurelius Leonidas, ex-magistrate and epimeletes, wrote the receipt.”

1 Εὐτύχης: P.Kellis 1 G. 60.3.

1–2. Mention of imperial land has not been found in other documents from the Oasis. Since the amount and indiction are repeated in the course of the text, this phrase may be more or less synonymous with εἰς ἀννώναν in line 4.

2–3 For artabas of barley by public measure, see O.Trim. 10.3–4 (conjecture). See also O.Douch 1.39 (corr. in O.Douch 2, p. 87), as well as P.Kellis 1 G. 79.8–9, where it also appears in connection with the military (a dromedarius).

4–5 For the garrison in question, see Introduction. The present ostrakon is the first evidence that these troops were horse-mounted archers.

For the phrase τῶν ἐν τῇ πόλει ἀγγαρευόντων see P.Cair.Masp. 1.67009; also P.Grenf. 2.95 (Sel. Pap. II 388) has annona for Scythians ἀγγαρεύοντες at a monastery. For the reading and uses of the word, see recently Worp 2012. For ἀγγαρεία as a soldier’s duty or being stationed in a place, see LSJ Revised Suppl., s.v., citing Cod.Just. 12.37.19.

6–7 An Aurelius Leonidas has not occurred before in the documents from the Oasis. The (Doric) form Λεωνίδας is attested several times, but never in the fourth century. Other versions of the name are more common, especially different spelling variants of Λεωνίδης, occurring over 500 times in papyri. Notably, an Αὐρήλιος Λεωνίδης is strategos and exactor of the Great Oasis in 369/70, the precise year to which our ostrakon may be dated, in SB 18.13252 (repr. SB 1.4513). Also in abbreviated form . . . ος Λεωνίδ(ου) occurs in O.Douch 4.399 (Kysis, fourth century).

6 ἔγραψα τὴν ἀποχὴν: Frequent in the Kellis documents, e.g., O.Kellis 1–3; 53; P.Kellis 1 G. 29.6–7. Other possibilities like ἐξέδωκα τὴν ἀποχήν (O. Strasb. 1.475 (fourth–fifth c., Thebaid)) or ἔδωκεν as in P.Kellis 1 G. 62, ἔδωκεν as in O.Kellis 65.6 or δέδωκεν as in O.Kellis 67.3–4 are less likely.

7 For title of ἄρξας, see Worp 1997a. Ex-archontes signing tax receipts in Kellis: e.g., O.Kellis 1–5, etc.

ἐπιμεληταί bringing barley to Mothis are also attested in O.Kellis 102.7–10, an account of transport animals: εἰς Μῶθ(ιν) ὁμοί(ως) Ἀπόλλονι ἐπιμελητ(ῇ) κτῆ(νος) α – to Mothis, likewise, for Apollon the epimeletes, 1 donkey.

Barley for the annona is also mentioned in O.Trim. 1.329 (350–370).

6. Receipt for wheat. 358/9, 373/4 or 388/9. (Plate 10.6)

Inv. 28, Area B, room B1, BF8 (embedded in the plaster of a niche), FN 13.

6.5 x 5.4 cm; complete. Text on convex side, perpendicular to the wheel marks.

Fabric: A1b.

| Ἐδεξάμην παρὰ Του | |

| Ψεμπνούθου Ψάι(τος) πυ- | |

| ροῦ ε ἀρτάβας καγ(κέλλους) εἴκοσι | |

| 4 | ὀκτὼ ὑπὲρ τοῦ ἀδελφοῦ |

| Παυσανίου καὶ β/ ἰνδικ(τίονος). | |

| σεσημίωμαι traces? | |

| Πεκύσιος. |

| 2 ψαι | 3 καγ | 4 ινδικ | 6 l. σεσημείωμαι |

“I received from Tou son of Psempnouthes, grandson of Psais, twenty-eight cancelli artabas of wheat for our brother Pausanias, and for the second indiction. I, NN son of Pekysis, have signed.”

1 The proper name Του is well attested in the Dakhla Oasis (P.Kellis 1 G. 34 and KAB 604, O.Kellis 1, 97, 109, 111, 287, O.Trim. 205, 249). We have excluded the genitive article for reasons of syntax.

2 It appears that there was already a defect in the surface at the time of writing.

4-5 The name Pausanias is common at Kellis, cf. O.Kellis 57.5n. with references. The appearance of a Pausanias in O.Kellis 137 and 255, from the West Church, is noteworthy.

If καί is indeed a conjunction, it is oddly placed. “Brother” in this instance probably means “colleague,” as often.

7. Receipt for chickens. 352/3, 367/8 or 382/3. (Plate 10.7).

Inv. 25. Area B, room B1, DSU14.

8.6 x 6.9 cm; complete. Text on convex side, parallel to the wheel marks.

Fabric: A1a.

| Δέδωκεν Λουκρήτις | |

| ὀρνίθια ἕξ, γί(νεται) ὀρ(νίθια) ϛ ὑπ(ὲρ) ἑνδεκά - | |

| της ἰνδικτίονος. σεσημί - | |

| 4 | ωμαι Τιμόθεος. |

| 1 l. Λουκρήτιος | 2 γι ορ υπ/ | 3-4 l. σεσημείωμαι |

“Lucretius gave six chickens, total, 6 chickens, for the eleventh indiction. I, Timotheos, have signed.”

1 The name Λουκρήτιος is unattested in the Oases and rare in the fourth century.

2 Kellis texts use both ὄρνεον and ὀρνίθιον, apparently without particular distinction; the word is sometimes abbreviated, leaving one in doubt about the correct form. For the first of these written in full, cf. O.Kellis 61 and 62; for the second, O.Kellis 64 and 65.

The 11th indiction likely corresponds to 352/3, 367/8 or 382/3 (see Introduction).

4 Individuals named Timotheos occur in the Kellis documentation with some frequency. The signer here could well be the same as in O.Kellis 79.

8. Receipt or order concerning wheat. Ca. 330–390. (Plate 10.8)

Inv. 660. Area B, room B11, DSU97, FN 11 + 12.

6.1 x 6.6 cm; nearly complete. Text on convex side.

Fabric: A11

The text is complete except at left, where a small piece is lost from the upper left corner and probably a narrow piece from the entire left side.

The ostrakon was found in an ashy dump layer deposited in corridor B11 after the building of the church complex, when B11 functioned as a street. On the basis of numismatic evidence, the dump layers in this space can be dated to a period from ca. the 330s to ca. the 380s.

This small and fragmentary ostrakon is of interest for its mention of a praepositus, presumably of the ala stationed in the Oasis rather than the praepositus pagi. He appears in the genitive, and probably about 8 letters or a little more stood before what we can read and restore. It is not obvious what most suitably fills that lacuna—whether the wheat was received from him, or according to his orders, or was to be delivered to his agent, in particular.

| [ ± 11 ] . υρ β . . . μου | |

| πραι]ποσίτου σίτ(ου) (ἀρτάβας) β. | |

| ᾽]ωσηπ σεσημίωμαι. |

| 2 σιτ⨪ | 3 l. σεσημείωμαι |

“. . . , praepositus, 2 artabas of wheat. I, Joseph, have signed.”

1 Τhere are too many letters for κυρίου μου, and no name ending in -μου, the most obvious reading at the end of the line, fits the text.

2 This line is the evidence that no more than 4 letters need to be lost at left here, and from this the probable lacuna in line 1 can be estimated.

3 There was probably room for more to have been written. Possibilities are that the amount of grain was given a second time; that the name was preceded with Αὐρ(ήλιος); or that the signature was indented.

9. Receipt for money. 264/5 or 232/3. (Plate 10.9)

Inv. 830. Area B, room B23, DSU147, FN 94.

11.4 x 17 cm; complete. Text on convex side.

Fabric: A1b.

The document is of interest for its early date and for the mention of Pmoun Berri, a toponym that may be the ancient name of the site (see Introduction).

This is the earliest of the Ἁin el-Gedida ostraka. The sinusoidal curve following ιβ in l. 1 is rather the symbol for a year than an indiction, as the 50 drachmas in l. 5 would have been a negligible sum by the mid-fourth century, when the indiction cycle becomes popular in documents from the Oasis. In fourth-century documents a single regnal date omitting the numerals for emperors other than the senior one9 is first attested under the First Tetrarchy and becomes visible from 308 onwards (according to this practice, year 11 could belong to the reign of Constantine I [316/7], or just possibly that of Valentinian I [373/4], although we have no clear examples in the Oasis that late), but once again neither of these is possible in our text given the sum of 50 drachmas for a year’s worth of rent. Therefore, ιβS must be a regnal year in the third century: the 12th year of Gallienus (264/5) or even as early as the 12th year of Severus Alexander (232/3). A date in the reign of Diocletian (295/6) is less likely. For a similar receipt for 40 drachmas for the fourth year, see O.Kellis 53 dated to the third century after 212.

The ostrakon was found in DSU147, a deposit immediately above the floor of room B23, which is dated on the basis of numismatic evidence to the early fourth century: coins from 314–315 (inv. 1038) and 316 (inv. 1044), see pp. 505 and 506). The ostrakon may have been originally embedded in the floor and therefore attributable to the earlier phase of the room when it still functioned as part of the temple. The coins, on the other hand, might have been deposited on the floor in a later phase, when the temple had already been turned into a pottery workshop (see Section 6.7).

| ιβ (ἔτους) Φαρμ(οῦθι) κθ ἔσχον | |

| Παύλου υἱο(ῦ) Μέρσιος ἀπὸ | |

| γεωργ(ίου) Πμοῦν Βερρι | |

| 4 | γενή(ματος) ια (ἔτους) ἀργυρίου |

| δραχμὰς πεντήκον[τα] | |

| (γίνονται) (δραχμαὶ) ν. αἴγρα(ψα) Αὐρ(ὴλιος) | |

| Αμ..ν( ) |

| 1 ιβS// φαρμ | 2 l. Παῦλος υιo | 3 γεωργ | 4 γενη/ ιαS// | 6 ⌡ S l. ἒγρα(ψα) |

“12th (year), Pharmouthi 29. I received from Paulos son of Mersis, from the georgion of Pmoun Berri, for the crop of the 11th (year), fifty drachmas of money, total, 50 dr. Aurelius Am-- wrote (the receipt).”

2 For a third-century occurrence of the name Paulos in the Oasis, see O.Kellis 21.1–2. We see no clear traces of any preposition before the name, but the name is slightly indented.

3 γεώργιον is generally taken to mean “field”, but often “farm” or “farmstead” is clearly more appropriate. A georgion can have a name, as in, e.g., P.Ross.Georg. 3.40.7 and SPP 20.86.5. It may well be close to epoikion in meaning here.

For the toponym Pmoun Berri, ‘New Well’ (from Coptic ⲃⲣⲣⲉ – new, young) see Introduction to this chapter. The toponym is attested in P.Kellis 1 G. 5.12 (there spelled Βερι), in O.Trim. 114 and in an unpublished ostrakon from Ἁin es-Sabil found in 2009, and means ‘New Well’. For more on wells and well toponyms, see O.Trim., Introduction; see also Wagner 1987: 279–83.

4–5 For cash rents in the third century, see Drexhage 1991: 193–248. The plot was likely planted with crops other than grain, since leases of land planted with wheat or barley consistently require the lessee to pay in kind.

7 Perhaps Ἀμμών(ιος).

10. Uncertain text: fragment of a draft of a contract? Fourth century. (Plate 10.10)

Inv. 8. Area A, room A25, clearance.

9 x 11.5 cm; broken at top left. Text on convex side, oblique to the wheel-marks.

Fabric: A1a with external cream slip.

Although little survives of this text, “this being invalid” tends to suggest contractual language (possibly related to a divorce contract? See P.Dura 31 and P.Oxy. 6.906). In all likelihood, the beginning of line 1 represents the end of a verb in the perfect, like ἐσχηκα. But exactly what the nature of the original text was, it is impossible to say. It may have been only a draft or a memorandum concerning a contract.

| ------- ].καπερη..[ | |

| τ]ῇ γυναικὶ σοῦ τὴν .[ | |

| ταύτην ἄκυρον οὖσαν |

“--

-- your wife --

-- this -- being invalid –”

1 One would expect to interpret these traces as περὶ after a verb in the perfect, but the letter after the rho does not resemble an iota. A kappa is also possible, but less likely. One is tempted to read περή, or even supplement περήλυσις (as a spelling variant of περίλυσις, cancellation; see divorce contract P.Cair.Masp. 1.67121.25, though room is scarce.

2 την.[ is rather not the beginning of a feminine name.

11. Uncertain text—a tag? Fourth century. (Plate 10.11)

Inv. 529. Area B, room B5, DSU36.

3.2 x 4.1 cm; complete? Text on convex side, oblique to the wheel-marks.

Fabric: A1.

| ε υἱὸ( ) Γενα / |

| 1 υιο |

“5, son of Gena /”

The meaning of ε is obscure. It may simply be a numeral representing the number of objects. Despite the lack of a numeral mark, it may stand for the fifth day of an unknown month.

The two marks on either side of the iota resemble u-shaped and circular strokes rather than a dieresis. For the abbreviation of υἱός / υἱοί as υιο (it is impossible to determine whether we are dealing with a singular or a plural in this case), see, e.g., O.Kellis 11.3; 37.2; 41.3. The raised diagonal stroke at the end cannot be an abbreviation, since Gena is written out in full. It may be the left stroke of a supralinear λ from the abbreviation λι for λίτραι, pounds, see O.Kellis 95.4. It may also be a check mark next to the name.

12. Uncertain text. Fourth century. (Plate 10.12)

Inv. 17. Area A, room A25, clearance.

5.8 x 2.1 cm; broken at bottom, left, and right. Text on concave side.

| ].ⲱ..ⲁⲓ ⲉⲧⲃⲏ[ ]ⲕⲛ[ | |

| -------- |

1 Probably Coptic (ⲉⲧⲃⲏ = ⲉⲧⲃⲉ, on account of), written in an unpracticed hand. At the start of the line, an alpha, lambda, or rho.

2 Speculation about these letters is probably futile; but they could represent the start of a second-person singular future verb.

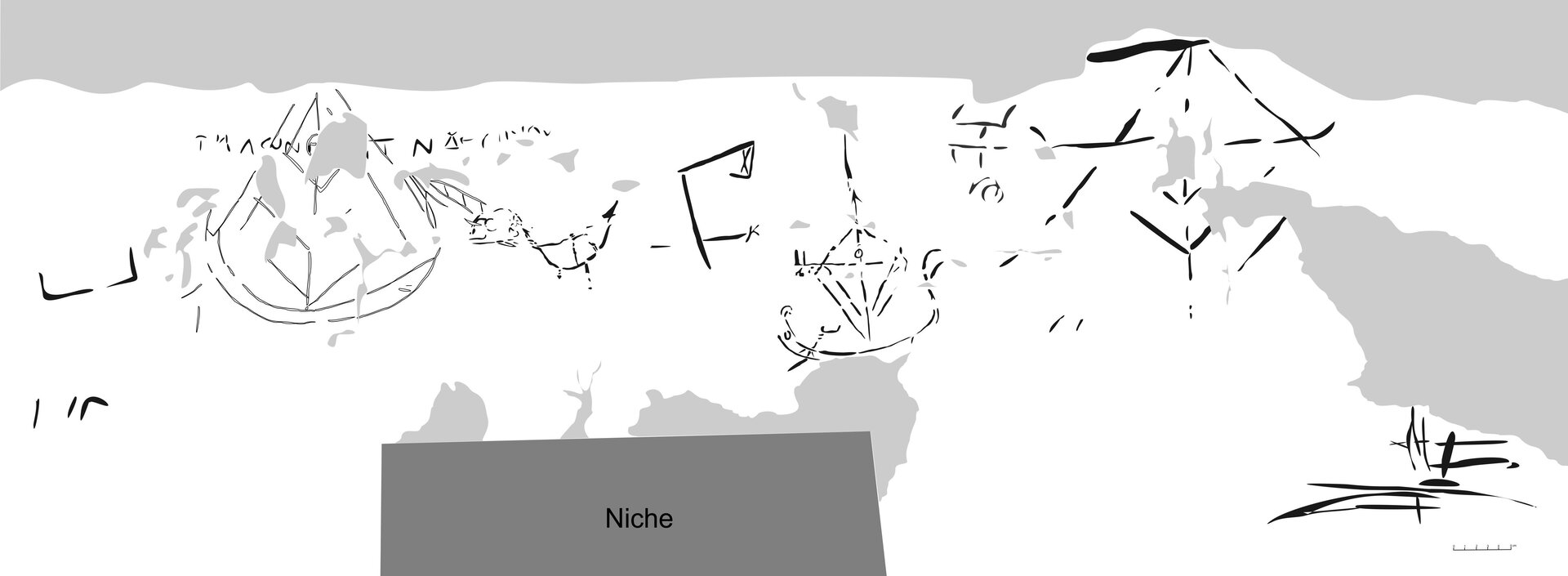

10.4 Inscriptions

All inscriptions were discovered within the church complex. Two, painted in black ink, were executed on the walls of its anteroom (B6) and one was carved in wall plaster in the church itself (B5). They seem to be contemporary to or later than the last phase of the complex and therefore should be dated to the second half of the fourth century. The north wall of room B6 also carries figural dipinti in black ink: a bird and two fragmentary representations of ships located to the right of and slightly lower than 1 on the whitewash frame surrounding a niche (Plate 10.13, Plate 10.14). A graffito of a ship scratched into the plaster surface is clearly later than this inscription, as it partly damages some of the letters. Only inscription 2, which refers to “one God”, is clearly religious in character.

1. Inscription in black ink. (Plate 10.15, Plate 10.16)10

Letters ± 1.5 cm high; indistinctive majuscules.

Area B, room B6, BF73 (north wall).

| ⲁⲡⲟⲗⲗⲱⲛⲓ[ⲟⲥ ϩ]ⲓⲧⲛ ϫⲉⲙⲛⲟⲩⲧⲉ | |

| κ . . |

“Apollonios on behalf of Jemnoute”

--

1 Only traces of letters at the beginning of the name are visible and the end is in lacuna. Kellis documents in Greek mention several individuals named Ἀπολλώνιος (O.Kellis 9.2-3; 68.4-5; P.Kellis 56.8) and Ἀπόλλων (O.Kellis 5.5; 72.5; 102.9; 147.1; P.Kellis 25.4; 61.11) or variants of the latter. ⲡⲟⲗⲗⲱⲛ is attested: P.KellisCopt. 45.7.

ϩⲓⲧⲛ takes the meaning of ὑπέρ rather than διά, since Apollonios is much more likely to be acting on behalf of Jemnoute, a female, than the other way round. For a similar meaning of ϩⲓⲧⲛ, see, e.g., P.Mich.Copt. 14 verso, where ϩⲓⲧⲛ ⲡⲉⲛⲉⲓⲱⲧ is translated as “De la part du Père (du monastère).”

ϫⲉⲙⲛⲟⲩⲧⲉ, a variant of the feminine name Τσεμνούθης, is not attested in this spelling, but several other variants are found in Coptic documents from Kellis (ϫⲙⲛⲟⲩⲧⲉ: P.Kellis 5 C. 25.64,66 and 44.19; ⲧϫⲉⲙⲡⲛⲟⲩⲧⲉ: 26.50; ⲧⲥⲉⲙⲛⲟⲩⲑⲏⲥ: 11.5; ⲧϣⲙⲛⲟⲩⲧⲉ: 19.53, 62; Τσεμνούθης: 11.address,1. See also P.Kellis 1 G. 71.43).

2 Faint traces of one or two letters are visible after the doubtful kappa. The letters in this line were smaller and more tightly spaced out than in l. 1.

2. Inscription in black ink. (Plate 10.17)11

Letters ± 2.5 cm high; rounded, indistinctive majuscules, neatly spaced out.

Area B, room B6, BF72 (west wall) near northwest niche.

| εἷς θεὸς ὁ βοηθ . . . . . . .[ |

One God, who helps (?) - -

For a discussion of the use of the common “one God” formula in different Near Eastern religious contexts, see Peterson and Markschies 2012. The inscriptions are also present in Egypt’s Western Desert (Shams ed-Din: I.Oasis 32,28; 38,50; 39,51; 41,58a; 43,66; and Bagawat: I.Oasis 62,1).

The reading of the faint traces after βοηθ is difficult. The word βοηθῶν is likely, considering the presence of the article ὁ after θεός. However, although the traces after theta could be read as a large omega, we do not see a nu. If instead the horizontal stroke is the bottom of a delta, we could be dealing with an abbreviation, βοηθ(ῶν), followed by a different word, possibly a name. The traces of the last two letters can be tentatively read as ιδ, in which case Δαουειδ would be the most plausible reading if indeed the letter that follows the theta is a delta.

3. Graffito. (Plate 10.18)12

Letters 1–2 cm high.

Area B, room B5, BF58 (north wall), western half of wall.

| Ὠρικενι δ β | |

| Ἰμουτε Μαχη γ |

1 The meaning of the letters delta and beta at the end of the line is obscure. The delta can be an abbreviation of a patronymic, a title (e.g. δεκανός, or διάκονος), but it may well be something entirely different. However, there is no abbreviation mark and we have no comparanda to aid in the deciphering of such a short, unusual abbreviation, if indeed this is what we are dealing with. The beta may be a numeral (followed by a gamma in an analogous role in the next line). What these numbers stand for, however, is unknown.

Most commonly attested in the Western Desert is the Greek version Ὠριγένης, also found in Kellis ostraka (O.Kellis 30.9 [162]; 51.2 [212-260]; 129.7 [third–fourth c.]) and the KAB (1386; 1407; 1762). This variant is a combination of other Coptic spellings attested in much later documents: ⲱⲣⲓⲅⲉⲛⲏ (P.KRU 93 [770–780]) and ϩⲱⲣⲓⲕⲉⲛ (O.Wadi Sarga 157 [seventh c.]).

2 An alternative reading of this line is Ἰμούτ(ης) Ἐμούχη(ος) Γ, with an eta in place of an epsilon in the patronymic.

Greek spelling of the common Egyptian masculine name Ỉy-m-htp (and var.). Ἰμουτ for Ἰμούτης: SB 20.14352.3 (Western Thebes, third–fourth c.); Ἰμουθ--: O.Kellis 222.concave.4.

What follows the personal name in line 2 may be a patronymic, possibly in abbreviated form. A Μαχητ is attested in KAB 1687 and a Μαχ-ε is found in O.Kell. 96.5.

A less likely alternative is Μουχη. Ἐμοῦχις and Μουχις are attested as names, but the are both rare and early. Mouchis as a toponym (several villages of that name are attested in the Nile Valley) is even less likely.

The gamma seems to be the numeral 3, but, as in line 1, what it stands for is obscure.

10.5 Figural Dipinti and Graffiti

The majority of the figural dipinti and graffiti are found on the north wall (BF73) of room B6, on the whitewashed plaster surface around a niche (Plate 10.13, Plate 10.14). In addition, one geometrical motif was incised on the south wall of the room (BF70). Wall BF73 bears numerous marks, both painted in black ink and scratched in the plaster surface, but only a few of the drawings are preserved well enough to permit identification. Besides the one inscription discussed above (1), it was possible to identify one dipinto of a bird, two dipinti of ships (one nearly complete and one fragmentary), and one graffito of a ship. Chronological relationships between the dipinti are impossible to determine, but the ship graffito (4) cuts and is therefore later than the inscription and the bird dipinto (3). Like the inscriptions, the figural dipinti seem to be contemporary to or later than the last phase of the church complex and should be dated to the second half of the fourth century.

It is difficult to say anything specific about the meaning and purpose of three representations of ships. The presence of ships in an oasis, away from navigable water courses, is somewhat perplexing,13 and one is tempted to seek an explanation in the symbolic meaning of the representations, all the more so that they appear in the context of a church complex. However, ships are not specifically Christian in their symbolism; boat graffiti are ubiquitous in the ancient world and in Egypt they are found on a wide variety of sites from all periods. Among representations of vessels dated to the third and fourth centuries, the story of Jonah is frequent, but so are other motifs, like the voyage of Odysseus and depictions of Nilotic scenery.14 Due to the state of preservation of the dipinti in black ink it is impossible to say whether they were part of a larger, more complex scene15 or, as seems more likely, constituted unrelated drawings executed on different occasions. In any case, no interpretation can be put forward with any degree of certainty.

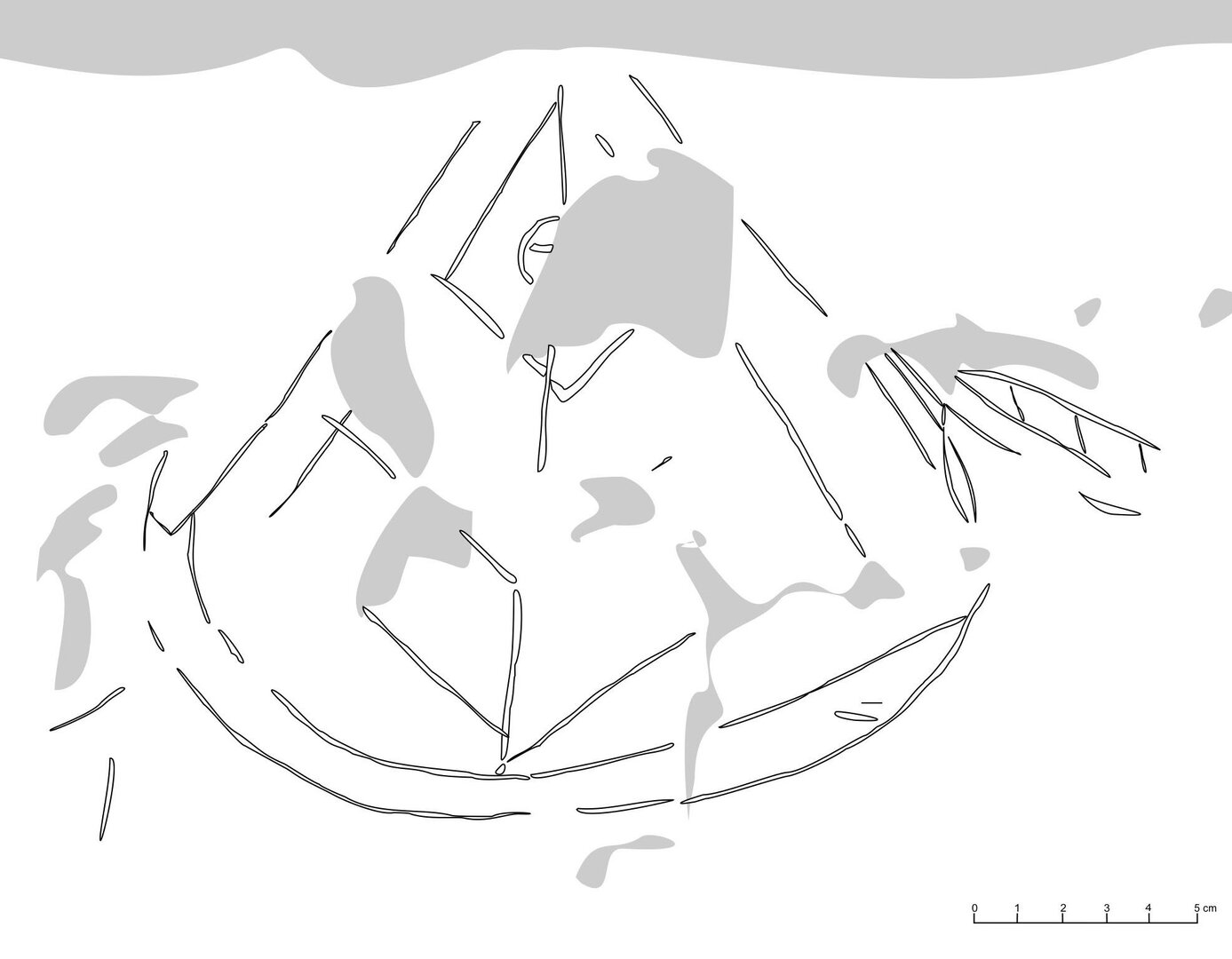

1. Ship. (Plate 10.19, Plate 10.20)

Dipinto in black ink; 15 cm x 20 cm; Room B6, wall BF73.

This dipinto is one of the best-preserved and most complete of the set. It is a relatively detailed representation of a sailed ship with a center mast and rigging. The drawing is faded in places and the plaster is broken in the lower part. As a result of damage and due to the cursory character of the sketch, some elements of the image are ambiguous. We cannot determine the exact type or size of the ship from this depiction, nor its method of construction. However, on the basis of parallels it appears to be a merchant ship rather than a military or fishing vessel.16

The mast stands vertically in the center of the hull. Its spindle is very long and rises high above the horizontal line that represents the yard. Curved lines likely representing the folds of a furled sail are fragmentarily preserved below the yard. There are two lifts connecting the yardarms to the masthead. Four ropes, possibly braces of the yard, trail down from the yardarms towards the base of the mast.17 Short lines extending from the yardarms (visible more clearly on the left-hand side) are enigmatic. They may represent the ropes used to tie up the sail at the ends of the yard.18 The circular element in the place where the yard is attached to the mast may be a block mast (calcet) or another contraption used to facilitate securing lines and standing rigging.19

The drawing of the hull is damaged at the bottom and in the center. The right-hand end is curved upwards and extends high, ending with what appears to be a massive acroter decorated with an ornament in the form of plumes, rendered as two curved lines. The left-hand end is rounded and terminates in an incurved possibly decorative element. The circular object represented near it is difficult to identify. Towards the left-hand side, there is a set of lines that appear to represent a steering oar with a handle.20 Judging from the location of this element, we can assume that the bow is on the right and the stern on the left. However, if indeed that is the case, the manner of depicting these elements is odd. In the majority of representations of Late Antique ships, it is the stern that is more pronounced and decorated with a plumed acroter (aphlaston), while the bow has a smaller, frequently incurved ornament.21 In this case, either the author of the dipinto confused the front and back of the ship or this is just intended as a decorative pattern.22

2. Ship (fragment). (Plate 10.21)

Dipinto; 30 x 23 cm; Room B6, wall BF73.

A dipinto in black ink located to the right of 1 is a fragmentary representation of a ship. It is large and executed in broad strokes, but the bottom of the image mostly faded or rubbed off, leaving only the mast, yard and rigging.

The masthead is not preserved. Two lines extending fore and aft from the top of the mast towards the bow and stern may represent the forestay and backstay, but their function is uncertain, as their bottom sections are no longer extant. Lines extending outwards from the mast to the yardarms likely represent braces, as it was the case in the more complete ship dipinto (1) described above.23

It is difficult to determine if any part of the series of strokes to the left of the yard was part of the same ship, for instance as an acroter adorning the stern, but this seems unlikely. Also the thick horizontal line above the mast is enigmatic and most probably did not belong to this representation.

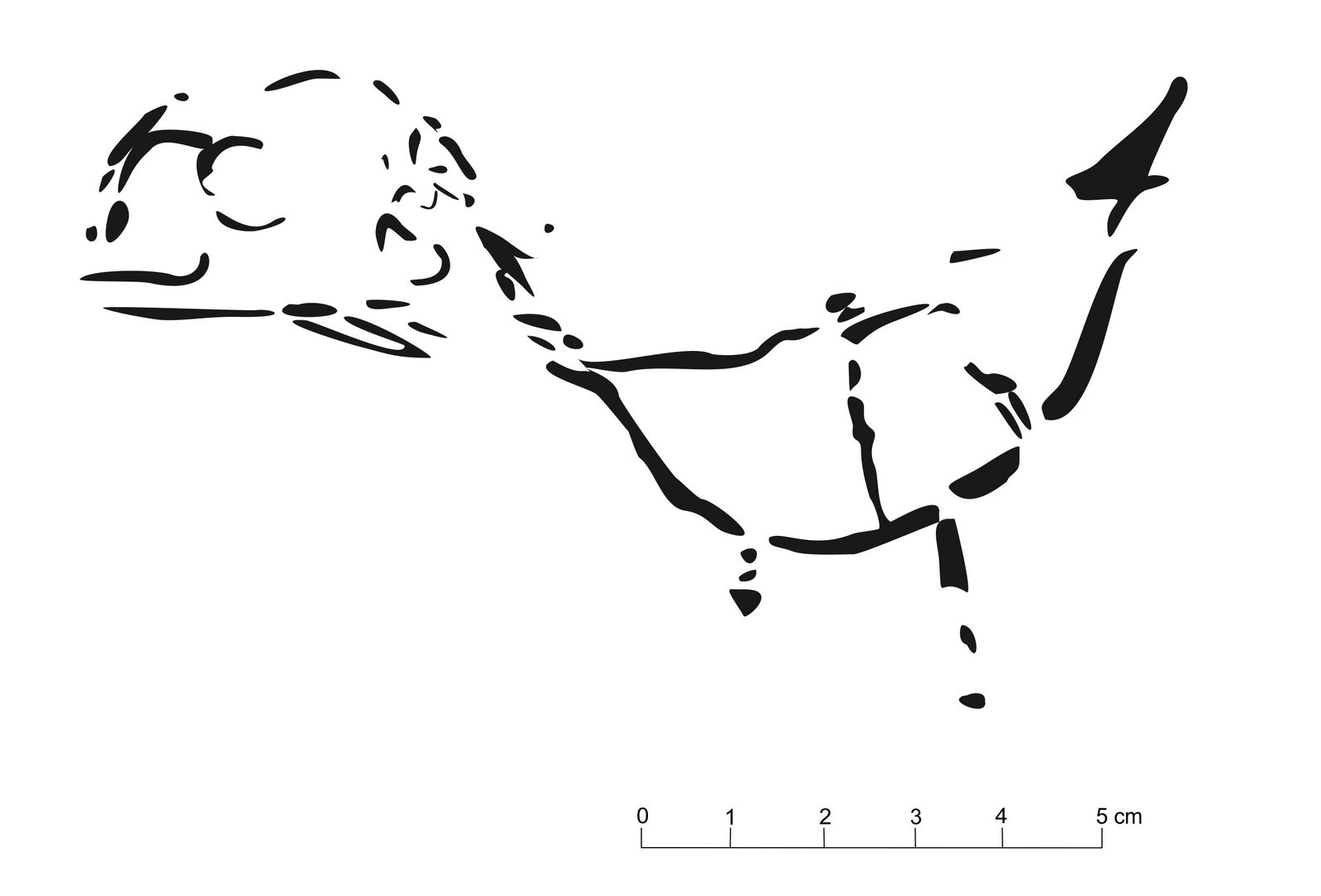

3. Bird. (Plate 10.22, Plate 10.23)

Dipinto; 14 x 7 cm; Room B6, wall BF73.

The third of the identifiable figural dipinti in black ink is located to the left of the two ships. It represents a bird that escapes more precise identification despite its relatively good state of preservation. The neck and upturned tail are short and the nearly vertical lines on the body may represent distinctive plumage or simply a schematically rendered wing. The short beak extends horizontally from the relatively large head. The large, circular element in the center of the head may be an eye. The two legs are only partly preserved, and therefore their length cannot be assessed beyond doubt.

Some distinctive features were included in this representation: a curved line connecting the tip of the beak and front of the head, as well as some strokes on the back of and below the head, but a comparison to other iconographic representations of birds, both in graffiti and other art forms,24 has not yielded parallels.

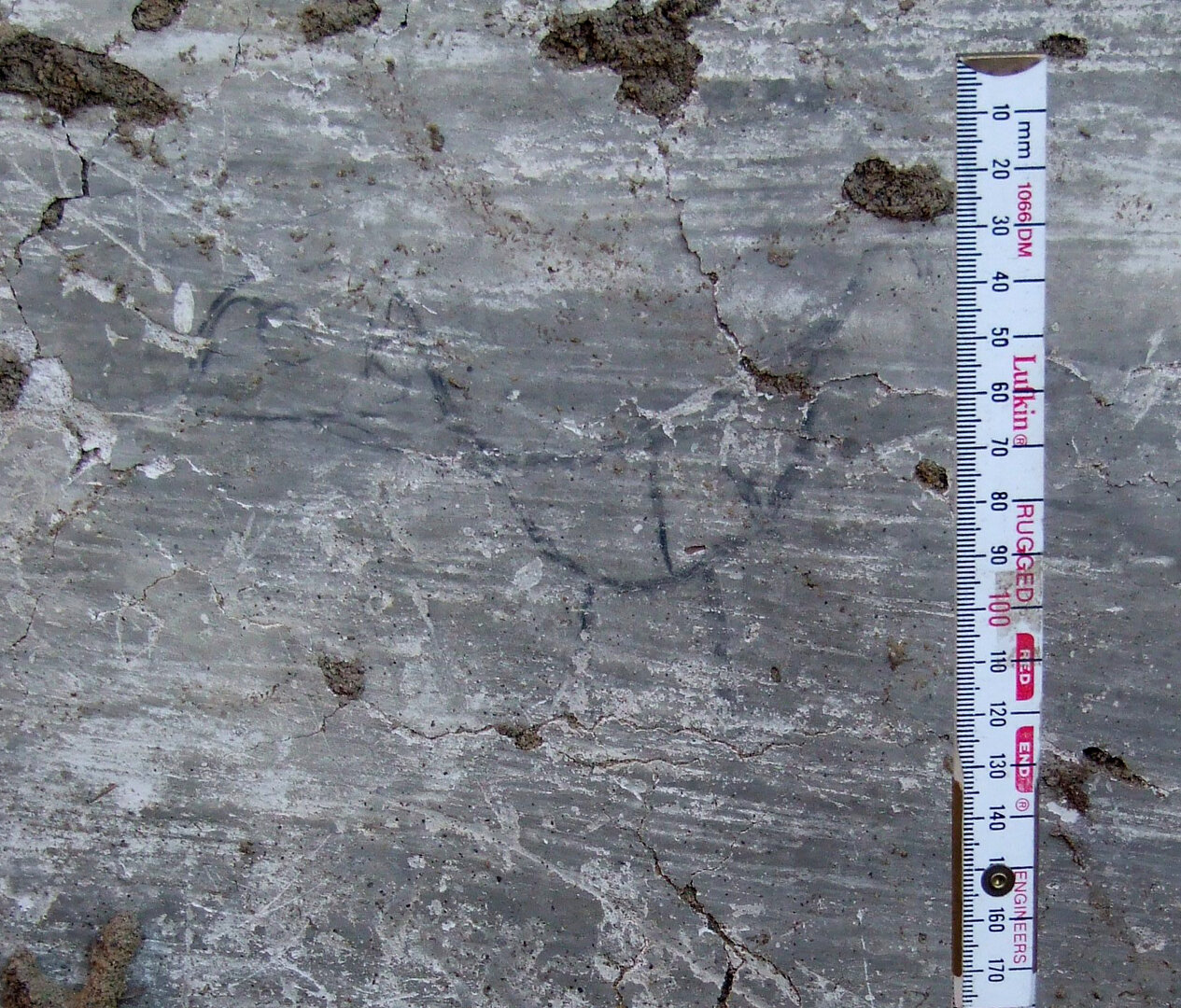

4. Ship. (Plate 10.24)

Graffito; 22 x 17 cm; Room B6, wall BF73.

The graffito is cut into the plaster on top of inscription no. 1 and the representation of the bird (3). The scratches are shallow and the lines are not clearly visible on the rough and cracked plaster. Aside from the top of the mast, the representation is complete.

The mast is located in the center of a rounded hull and the rigging (possibly the forestay and backstay) extends from a central point above, maybe the lost top of the mast, down towards the bow and stern. The yardarms and sail are not visible, but there are diagonal lines representing shrouds or stays supporting the mast.25 The left-hand end of the hull was likely the stern, since it rises higher than the other end and below it there are two lines that may have represented a steering oar. Above the right-hand end of the hull, most likely the bow, there are a series of intersecting lines that are difficult to interpret but may represent a decorative element.26

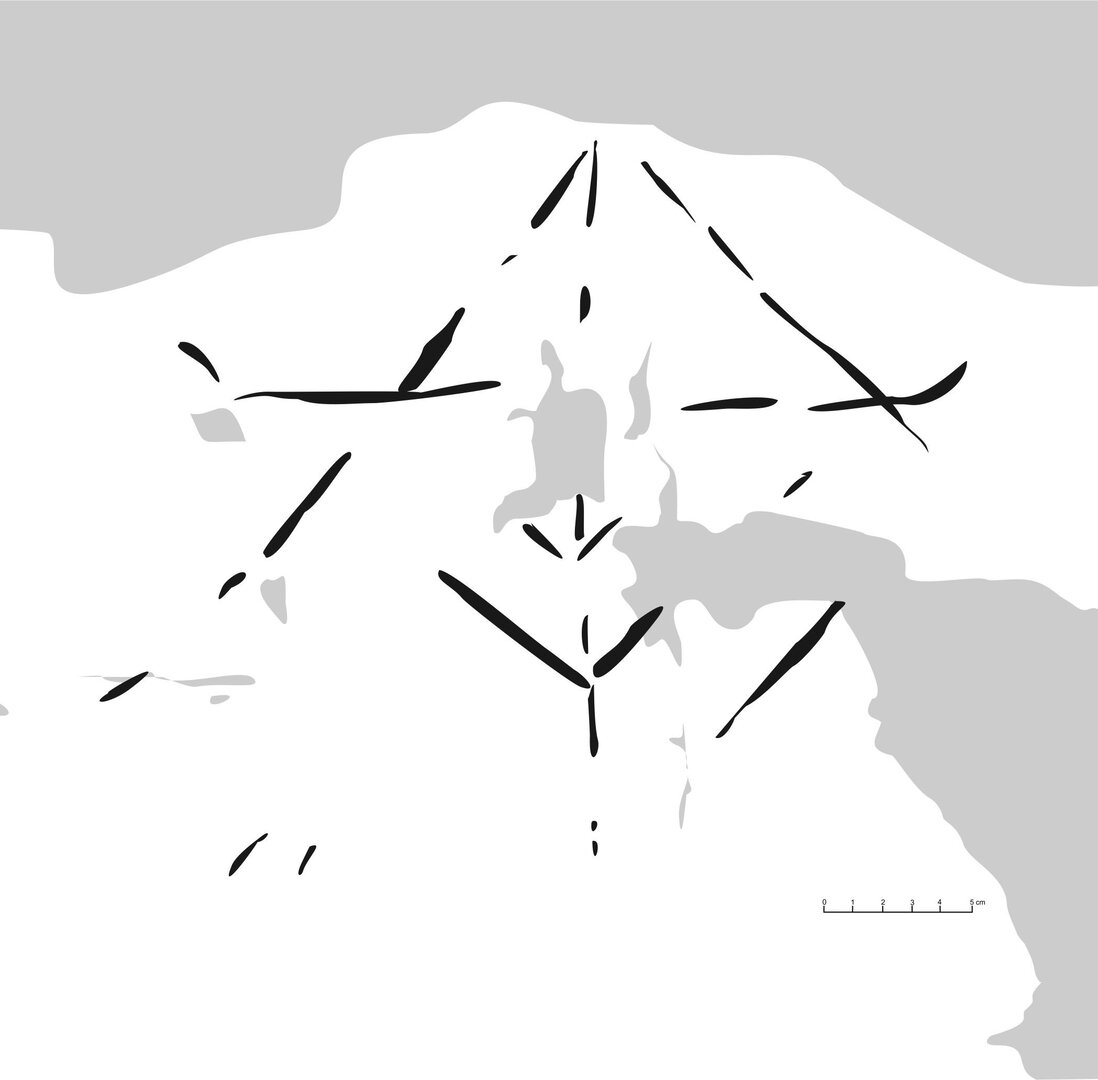

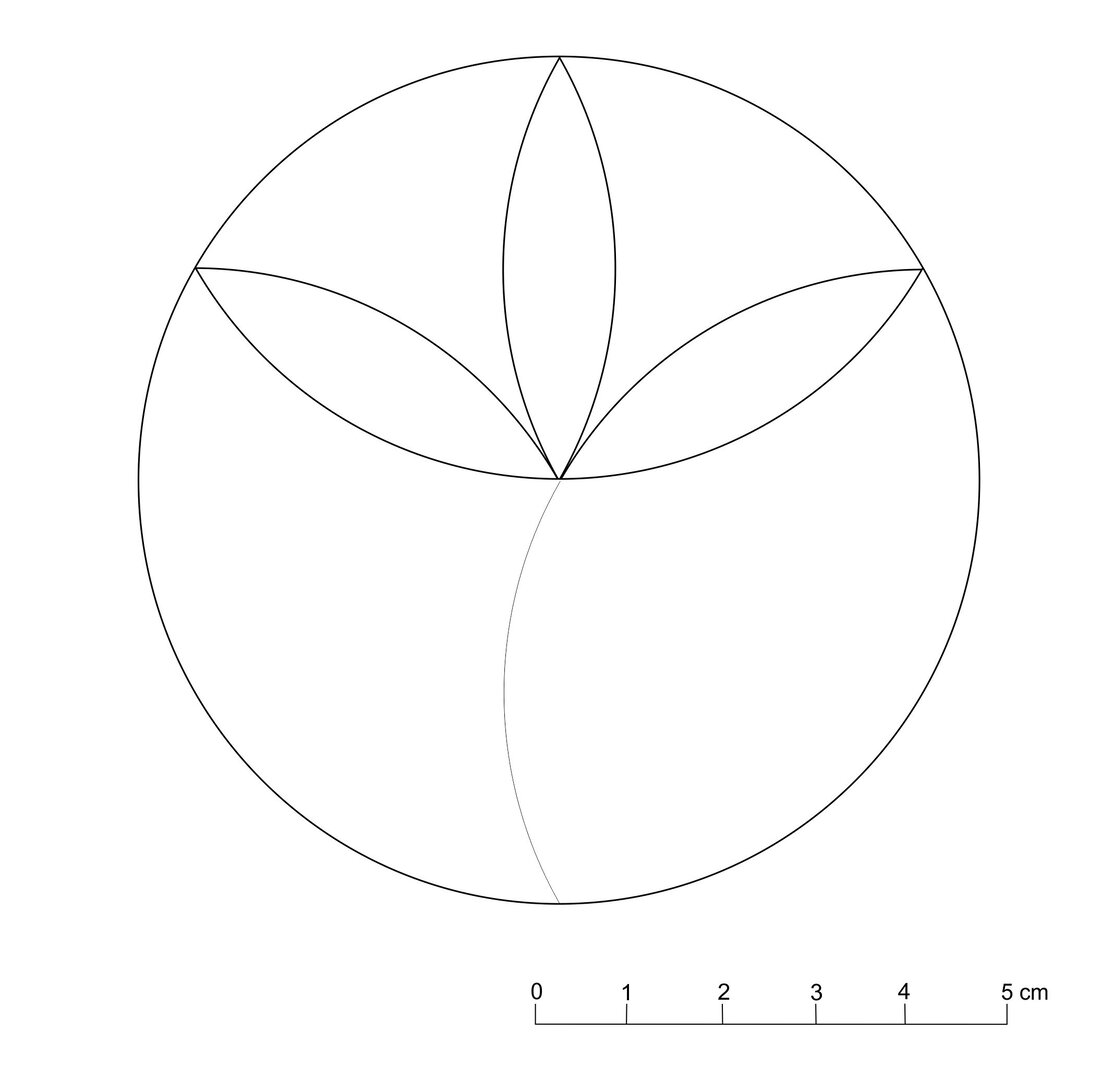

5. Rosette. (Plate 10.25)

Graffito; diam. 9 cm; Room B6, wall BF70.

The rosette was incised into white plaster covering the south wall of room B6 (BF70). The motif consists of a circle and three spindle-shaped petals inscribed into it. A faint line that formed one side of a fourth petal is visible in the lower part. In its complete form, such a rosette had six petals. The design was made by drawing seven identical interlinked circles, one in the center and six with their central points located on its circumference at regular intervals. The motif, usually repeated to form a pattern, is common in contemporary decoration, including wall paintings in houses in the Dakhla Oasis.27 The pattern is also not uncommon in graffiti,28 which show isolated rosettes drawn both with the help of a compass and freehand. In this case the drawing is incomplete, with only the central circle and the sections of circles that formed four of the petals.

10.6 Notes

See Bagnall and Ruffini 2012: Introduction; see also Wagner 1987: 279–83.↩︎

See F. Leemhuis on El-Qasr, in Report to the Supreme Council of Antiquities on the 2005–2006 Season Activities of the Dakhleh Oasis Project, pp. 69–70, available online at http://artsonline.monash.edu.au/ancient-cultures/files/2013/04/dakhlehreport-2005-2006.pdf, and subsequent reports of the Qasr Dakhleh Project accessible on the same website.↩︎

Gardner 2012: 471–74.↩︎

Gardner 2000: 247–57 (esp. 254).↩︎

Bagnall 1997: 75, 81–82.↩︎

The editors are indebted to Grzegorz Ochała for his valuable suggestions on the reading and interpretation of this ostrakon.↩︎

ⳁ ⲡⲁϩⲁⲙ ⲡⲕⲉⲫⲁⲗ( ) ⲉϥⲥϩⲁⲓ and ⳁ ⲡⲁϩⲁⲙ ⲡⲕⲩⲫ( ) ⲡⲉⲧⲥϩⲁⲓ (Paham the foreman writes…). See Gardner 2012: 471 and 473.↩︎

See Bagnall and Worp 2004: 44; Gardner, Alcock, and Funk 1999; Gardner, Alcock, and Funk 2014.↩︎

See also Plate 3.50.↩︎

See also Plate 3.51.↩︎

See Plate 3.25.↩︎

For other ship graffiti in the desert, see, e.g., Pomey 2012; we are very grateful to Patrice Pomey for his insightful comments on this material; see also Fakhry 1951: figs. 44, 69, 93, 94, and Sidebotham 1990.↩︎

See the Navis II Project database at www2.rgzm.de/navis2. The main reference works on naval iconography are still Casson 1971 and Basch 1987. For ships’ graffiti, see also Dijkstra 2012: 73–79.↩︎

For instance, see graffiti depicting multiple ships in Langner 2001: pl. 140–143.↩︎

Langner 2001: 118–20.↩︎

The closest parallel among graffiti comes from Gebel Silsileh; see Langner 2001: pl. 123, no. 1944. Other similar representations in graffiti: Langner 2001: pl. 119, no. 1893 (Pergamon), pl. 122, nos. 1931–33 (Nymphaion), 1938 (Pompeii), pl. 123, nos. 1945–6 (Silsileh), pl. 131, nos. 2026 (Alexandria, Anfouchi), 2035–37 (Delos), pl. 132, nos. 2039 (Delos), 2044 (Ostia), and 2047 (Pompeii). In decorative arts (mosaics, wall paintings), this type of representation is much less common than depictions of standing rigging and braces extending fore and aft from the mast and sail. See, e.g., Pekáry 1999: 258, Rom–Ci67.↩︎

Possible parallels, though rendered much less schematically, are: Pekáry 1999: 246, Rom–Ci12; Yacoub 1995: figs. 85–86. In graffiti, see Langner 2001: pl. 145, no. 2235 (Delos). The elements at the masthead and yardarms may also be pennants (Casson 1971: 246 and fig. 149).↩︎

For parallels, see Langner 2001: pl. 132, no. 2044 (Ostia) and Pekáry 1999: 206, I–P10 and 290, Rom–M57; Casson 1971: 232–33.↩︎

For depictions of steering oars with handles, see Brenk 2000: 453, n.41; Dougga ship 5 (Yacoub 1995: figs. 85–86). Casson 1971: 232–33 (fitting for the halyard, most likely made of bronze).↩︎

Langner 2001: pls. 116–144, passim; see also, for example, Pekáry 1999: 286, Rom–M43; Yacoub 1995: figs. 60, 73, 85 and 86; Brenk 2000: 453, n. 41. On merchant galleys that featured an aphlaston, see Casson 1971: 158.↩︎

Yacoub 1995: fig. 73.↩︎

See footnote 17. ↩︎

Langner 2001: pls. 104–11.↩︎

For similar representations, see Langner 2001: pl. 122, no. 1934 (Nymphaion); pl. 123, no. 1953 (Nymphaion).↩︎

See Langner 2001: pl. 130, no. 2021 (Benghazi) and 2023 (Rome).↩︎

E.g., the Villa of Serenos at Amheida (personal observation).↩︎

See Langner 2001: 29–30, pls. 4 and 5. Medamud: Cottevieille-Giraudet 1931: 67, no. 136; Elephantine: Jaritz 1980: 84, no. F20; Syene: Dijkstra 2012: 105, no. 172; as a Christian symbol: Abydos: Piankoff 1960: 149, fig. 16; Esna: Sauneron and Jacquet 1972: 1:70–71.↩︎