12 Animal Bone Remains from ʿAin el-Gedida

This is an online digital edition from ISAW Digital Monographs. The print edition of this work can be consulted at https://isaw.nyu.edu/publications/isaw-monographs/ain-el-gedida

12.1 Materials and Methods

Over 1900 animal bones and fragments recovered from the excavations at ʿAin el-Gedida in the Dakhla Oasis in Western Egypt were studied during January of 2011. The following information was recorded for each bone fragment: species, body part, portion, and degree of fragmentation. The condition of the bones, including evidence for weathering, gnawing, and butchery, was also recorded. Ageing data were based on both epiphyseal fusion of the long bones (Silver 1969) and dental eruption and wear (Grant 1982), and bone measurements were recorded following von den Driesch 1976. Measurements were taken to the nearest 0.1 mm using a vernier caliper. The data were recorded on a personal computer using FAUNA, a Windows-based update to the ANIMALS program (Crabtree and Campana 1987; Campana 2010).

12.2 Results

The animal species identified are listed in Table 12.1, and a complete faunal inventory is available from the authors. Bones that could not be identified to species were assigned to a number of higher-order taxa. These include large mammal or “cattle-sized” fragments and small artiodactyl or “sheep-sized” fragments. The fowl-sized remains are almost certainly chicken, since no other bird species was identified, and the equid remains are likely to be donkey. The rat-sized rodents are probably rats. As is the case for many other Roman-period sites in Egypt (see, for example, Hamilton-Dyer 2001), the faunal remains were identified without access to a systematic comparative collection. The identifications were based on identification guides (e.g., Cohen and Serjeantson 1996, Schmid 1972) and personal experience.

As Table 12.1 shows, the ʿAin el-Gedida faunal collection is dominated by the remains of domestic mammals, including pigs, caprines (sheep and goats), donkeys, and cattle. Small numbers of both sheep and goat bones were identified, following Boessneck, Müller, and Teichert 1964, but the vast majority of the remains were indeterminate sheep/goat fragments. All the identified bird bones were those of domestic chickens, and chickens are the most common bird species at the neighboring site of Amheida as well. Chickens would have been an important source of both meat and eggs. Despite the presence of a dovecote, there was no clear evidence for pigeons (Columba livia) at the site. This is not unexpected. While both chickens and pigeons were recovered from the House of Serenos and the adjacent bath complex, chicken bones far outnumbered pigeon bones. Many of the bones from ʿAin el-Gedida show cracking and fragmentation as a result of salt encrustation (see below), and many of the bird bone fragments are small pieces of bone that are difficult to identify to species. If pigeons were raised primarily for their manure, their bones are less likely to end up as domestic rubbish than chicken bones. A small number of gazelle (Gazella dorcas) bones was recovered, indicating that animal husbandry was supplemented by occasional hunting.

Although the ʿAin el-Gedida bones were carefully collected, many were in a relatively poor state of preservation. 98 bone fragments were clearly burned or calcined, and burning can often lead to bone fragmentation. Many of the bones were encrusted with salt deposits, and this may also have led to bone fragmentation as well. A number of the bones showed clear evidence for rodent gnawing, but very few had obvious signs of weathering.

The species ratios for the large domestic mammals were calculated based on fragment counts or NISP (number of identified specimens per taxon), following Lyman 2008. In these calculations, the equid remains were included with the identified donkey bones. The species ratios are shown in Table 12.2, along with the data from Areas 1 and 2 at Amheida. Area 1 is a third-century middle class household that was involved in property management and/or transportation1, while Area 2 is a wealthy fourth-century urban villa. The data show that the ʿAin el-Gedida assemblage was dominated by the remains of pigs, followed by caprines and donkeys; cattle bones were relatively rare. When compared to the large assemblage from Area 2 at Amheida, the ʿAin el-Gedida faunal collection includes relatively more caprines and donkeys and somewhat fewer cattle and pigs. Both the ʿAin el-Gedida assemblage and the Area 2 faunal collection are dominated by the remains of pigs. The Area 1 assemblage, on the other hand, includes relatively more cattle and donkeys and absolutely no pigs at all. McKinnon (2010) has shown that increased pork consumption is characteristic of Roman sites throughout the Mediterranean, and we have argued elsewhere (Crabtree and Campana 2016) that the high proportions of both pigs and chickens seen at Amheida Area 2 may reflect a high-status “Romanized” identity. The high numbers of pigs seen at ʿAin el-Gedida may also be a sign of a strong Roman identity. The higher proportions of donkeys and caprines at ʿAin el-Gedida are probably more typical of rural sites in Egypt.

Close examination of the cattle remains from ʿAin el-Gedida suggests that they were primarily working animals. All three first phalanges (Table 12.3) show evidence for lipping on the proximal joint surface. This pathological condition is likely to be the result of traction, i.e., the use of cattle to pull ploughs and carts (Bartosiewicz, Neer, and Lentacker 1997).

Pigs, on the other hand, seem to have made up a substantial part of the diet at ʿAin el-Gedida, as they did at Amheida Area 2. All parts of the pig skeleton are represented in the faunal assemblage (Table 12.3), although skull fragments, maxillae, and mandibles are particularly well represented. The mandibles provide evidence for the ages at which the pigs were killed (Table 12.4). Mandible wear stages (MWS) were calculated for 22 complete or nearly complete mandibles based on the state or eruption or wear on the first, second, and third molars. The youngest pigs (those with a MWS less than or equal to 6) were barely past the suckling stage. These pigs show limited wear on their deciduous (milk) teeth, and they were less than 6 months old when they were slaughtered. These animals would have provided a relatively small amount of meat, but the meat would have been very succulent. Some of the rent deliveries in the Kellis Agricultural Account Book were specifically of a piglet (see Bagnall 1997). The oldest pigs in the assemblage (MWS of 28 to 38) were slaughtered as the third molar was coming into wear. The pigs would have just reached bodily maturity at this age, approximately 2–3 years. No elderly pigs were recovered from the ʿAin el-Gedida assemblage.

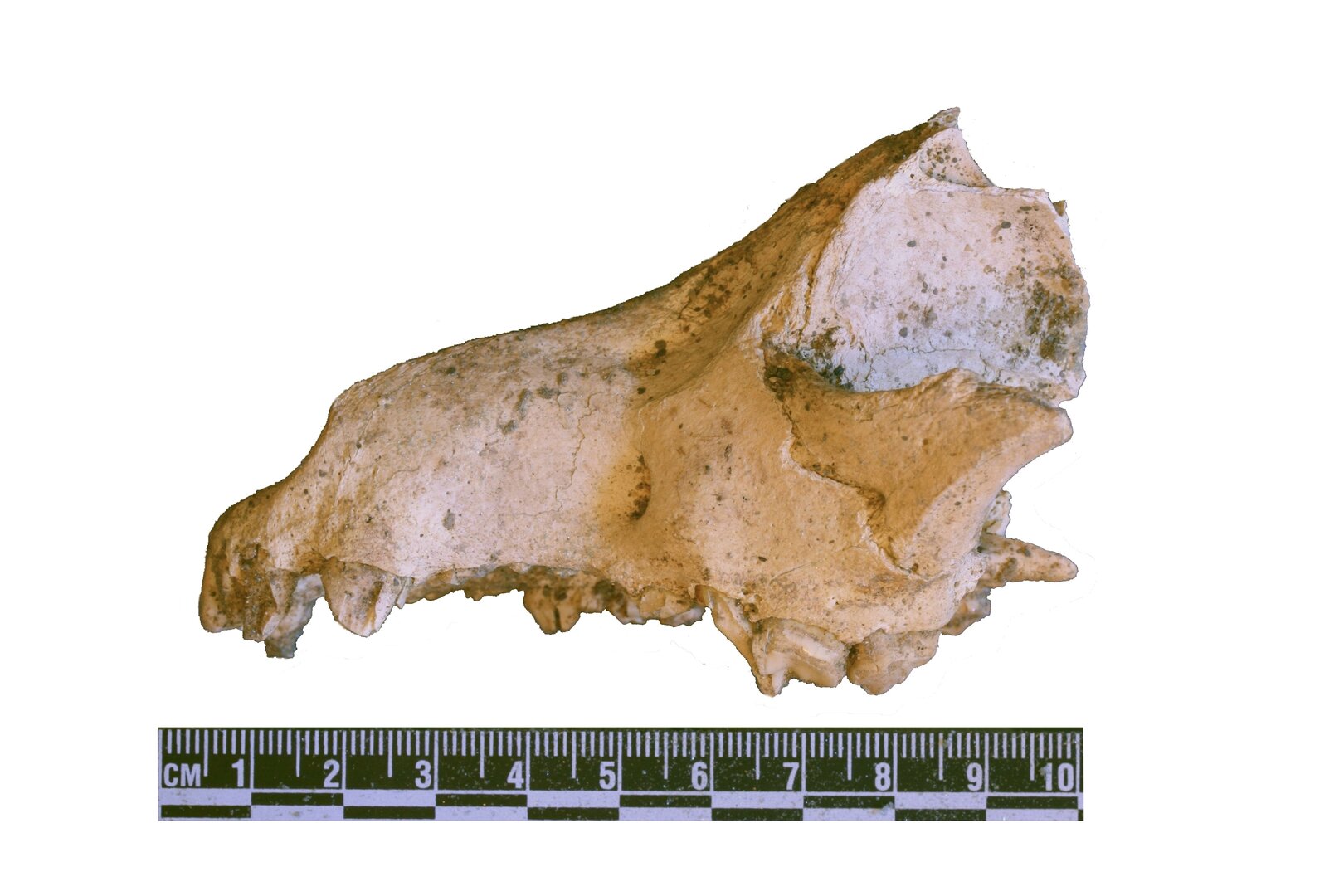

Not all the faunal remains recovered from ʿAin el-Gedida were the remains of meals. The remains of commensal species, including a dog, a cat, and rodents, were well represented in the faunal assemblage. A partial cat skeleton was recovered from room B10, and the remains of a dog were recovered in room B19. Two views of the dog’s skull are shown in Plate 12.1. The dog skeleton included a complete radius with a greatest length (GL) of 160.5 mm. This radius came from a dog with a withers height of about 51.7 cm (using Koudelka’s factors following von den Driesch and Boessneck 1974). Although the ʿAin el-Gedida assemblage produced a substantial number of donkey bones, there is no clear butchery evidence to suggest that they were part of the diet.

12.3 Conclusions

The faunal assemblage from ʿAin el-Gedida is what might be expected from a Late Roman agrarian site. Donkeys and cattle are likely to have served as working animals, while pigs, caprines, and chickens played a major role in the diet. The site was populated by commensal animals, including cats, dogs, and rodents. The diet was supplemented by occasional gazelle hunting, but most of the meat was derived from domestic sources.

| N | |

|---|---|

| Domestic Mammals | |

| Donkey (Equus asinus) | 58 |

| Cattle (Bos taurus) | 32 |

| Sheep (Ovis aries) | 2 |

| Goat (Capra hircus) | 6 |

| Sheep/goat | 58 |

| Pig (Sus scrofa) | 240 |

| Dog (Canis familiaris) | 47 |

| Cat (Felis catus) | 5 |

| Wild Mammals | |

| Gazelle (Gazella dorcas) | 3 |

| Domestic Birds | |

| Chicken (Gallus gallus) | 8 |

| Higher order taxa | |

| Large mammal "cattle-sized" | 29 |

| Small artiodactyl | 118 |

| Equid | 4 |

| Rodent, cf. Rat (Rattus sp.) | 12 |

| Unidentified rodent | 8 |

| Small carnivore | 2 |

| Small mammal | 4 |

| Chicken-sized bird | 5 |

| Unidentified mammal | 1277 |

| Unidentified bird | 22 |

| Unidentified | 2 |

| Total | 1942 |

| Gedida NISP | Gedida %NISP | Area 1 NISP | Area 1 %NISP | Area 2 NISP | Area 2 %NISP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle | 32 | 4.0 | 22 | 48.9 | 240 | 17.3 |

| Sheep/goat | 66 | 16.5 | 20 | 44.4 | 90 | 6.5 |

| Pig | 240 | 60.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1037 | 74.7 |

| Donkey | 62 | 15.5 | 3 | 6.7 | 21 | 1.5 |

| Total | 400 | 45 | 1388 |

| Anatomical Element | Cattle | Caprine | Pig | Donkey |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skull fragment | 4 | 1 | 27 | |

| Horn core | 4 | 23 | ||

| Maxilla | 1 | 5 | 42 | 1 |

| Mandible | 3 | 6 | 4 | |

| Hyoid | 1 | |||

| Vertebrae | 4 | 14 | ||

| Rib | 5 | |||

| Innominate | 3 | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| Femur | 2 | 2 | 12 | 2 |

| Patella | 1 | |||

| Tibia | 1 | 4 | 11 | 3 |

| Fibula | 3 | |||

| Scapula | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Humerus | 1 | 9 | 1 | |

| Radius | 6 | 5 | 1 | |

| Ulna | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| Astragalus | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Calcaneus | 3 | 1 | ||

| Carpals | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Tarsals | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 |

| Metacarpus | 1 | 1 | ||

| Metatarsus | 3 | 3 | 6 | 4 |

| Metapodial | 1 | 10 | 2 | |

| First Phalanx | 3 | 1 | 8 | 6 |

| Second Phalanx | 1 | 1 | 6 | 4 |

| Third Phalanx | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| Sesamoid | 5 | |||

| Loose teeth | 4 | 17 | 30 | 13 |

| Total | 32 | 66 | 240 | 62 |

| MWS | N |

|---|---|

| 1 | |

| 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 2 |

| 4 | |

| 5 | 2 |

| 6 | 1 |

| 7 | |

| 8 | 1 |

| 9 | 1 |

| 10 | 1 |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | 1 |

| 14 | 2 |

| 15 | 1 |

| 16 | |

| 17 | |

| 18 | 1 |

| 19 | 1 |

| 20 | 2 |

| 21 | |

| 22 | |

| 23 | 1 |

| 24 | |

| 25 | |

| 26 | |

| 27 | |

| 28 | 1 |

| 29 | 1 |

| 30 | |

| 31 | |

| 32 | 1 |

| 33 | |

| 34 | |

| 35 | |

| 36 | |

| 37 | |

| 38 | 1 |