2 Topographical and Architectural Survey of Mounds I-V

This is an online digital edition from ISAW Digital Monographs. The print edition of this work can be consulted at https://isaw.nyu.edu/publications/isaw-monographs/ain-el-gedida

2.1 Mound I

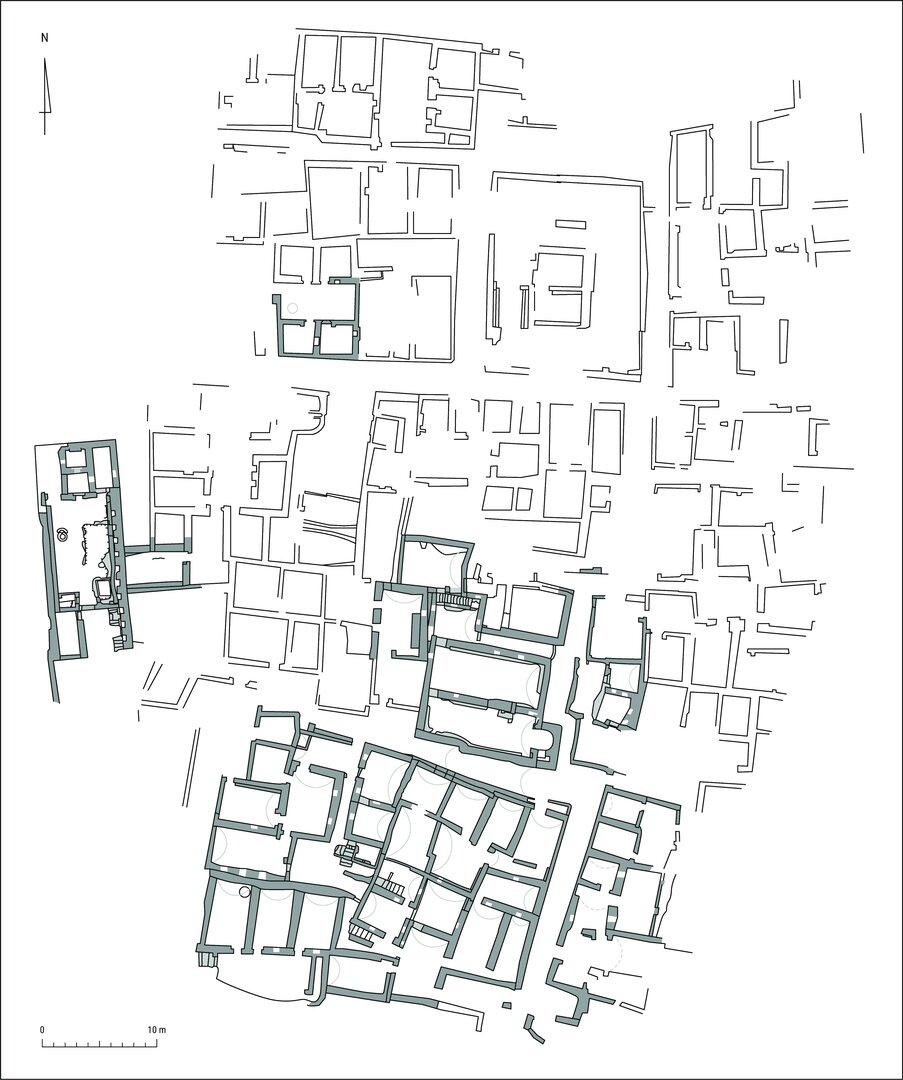

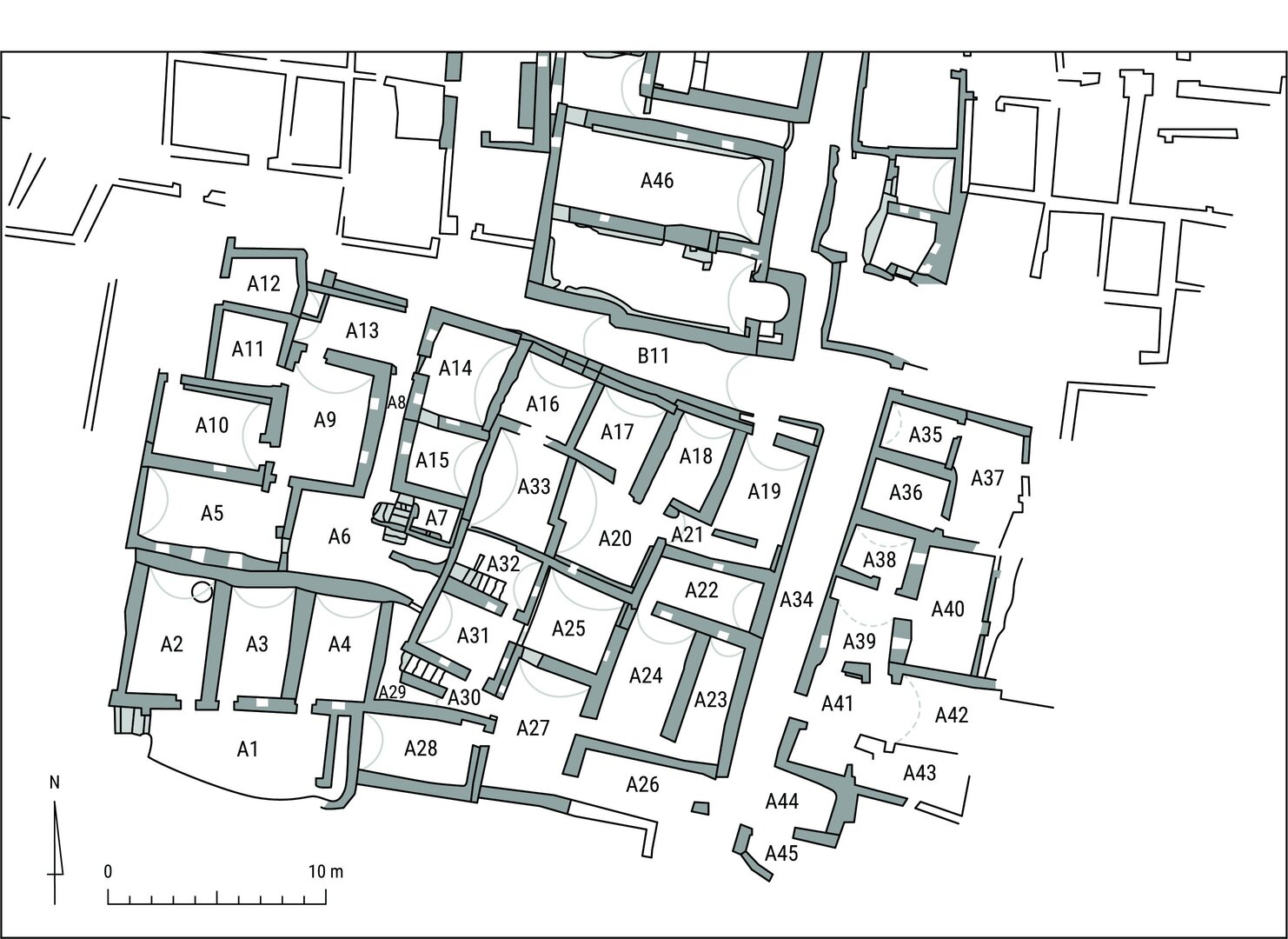

Mound I, where both the Egyptian and the international missions conducted intensive archaeological investigation, was, for the sake of clarity in the documentation, artificially divided into two separate areas: area A, corresponding to the southern part of the hill investigated by the SCA in the mid-1990s, and area B, to the north of area A and roughly occupying two thirds of the whole mound (Plate 2.1, Plate 2.2).

2.1.1 Area A

Although no documentation survives from the original investigation of area A, the topographical and architectural survey that was carried out by our team resulted in a significant amount of information on the buildings located in the southern half of mound I (Plate 2.3, Plate 2.4).

In this sector, the settlement gives the impression of having developed from a smaller, centrally located core of buildings into a larger complex extending toward the edges of the mound. The highly irregular layout shows that several rooms were not built following a systematic plan. It seems, instead, that they were constructed at different times, with mud bricks often laid out in a very poor construction technique and with the walls of the later structures abutting the outer walls of the earlier buildings.1 Unambiguous archaeological evidence was found for this addition of architectural features to earlier structures, which were often subject themselves to heavy alterations (as, for example, in room A6, discussed below). It is not possible to say if area B to the north reflects a similar situation and comparable patterns of development and expansion, as it remains largely unexcavated. Instead, area A, in which most rooms had been the object of complete or partial excavation in the 1990s, allows a more comprehensive picture of the topography of mound I in its southern part.

Further evidence for the existence of a multi-phased process of renovation and alteration of architectural features at the site is offered by the discovery, in a few rooms of area A (more extensively in rooms A9 and A25), of foundation trenches belonging to earlier walls.2 The trenches were hidden below compacted mud floors, which were laid out as the last stage of architectural alterations taking place in those rooms. These changes seemingly entailed not minimal restorations of walls, but rather drastic variations in the layout and, possibly, in the dimensions of the rooms, involving the destruction of earlier walls and the building of new, and often differently oriented, ones.

No easily identifiable domestic units were recognized in area A. Two sets of partially excavated rooms (A35–A37 and A38–A40), located along the southeastern edge of mound I, have a particular layout, consisting of two roughly square rooms built next to each other and opening onto a larger rectangular space. This spatial arrangement is quite similar to that of another set of rooms identified during the excavation of a test trench in the northern half of the hill (rooms B1–B3, cf. below). In the latter case, the large rectangular courtyard opens onto an additional set of two square rooms, but it is not possible to know if this was also the case for rooms A35–A37 and A38–A40, since the area occupied by these spaces was excavated only in part. Rooms B1–B3, and the two unexcavated rooms to the north, were identified as a relatively small and compact building of a domestic, residential nature, even though its overall arrangement of rooms does not seem to reflect standard types of domestic architecture in Greco-Roman Egypt generally or in the Dakhla Oasis in particular.

In most instances, the rooms surveyed in area A do not belong to small, separate buildings, but are rather interconnected to form a complex network, which extends throughout the southern part of the hill. More in detail, the topographical map of mound I reveals the existence of a large cluster of interconnected spaces in the northwestern part of area A and including rooms A5–A7, A9, A10–A11, A13 (and possibly A14–A15 to the east of passage 8). This very large set of spaces is, in fact, connected, through a very narrow corridor (A29, located in the southeast corner of room A6) and space A30, to rooms A25 and A31–A32 in the middle of area A (with evidence of staircases leading to roofs or an upper story). From the same narrow space A30, one could also enter room A27 and from there reach rooms A28, A26 (which seems to have been the main entrance into the latter set of rooms), and A24 (opening also onto A22 and A23) in the southern part of the mound. The only building that seems to have been, at least in its latest occupational phase, physically separated from the surrounding spaces of this packed built-in environment, is located just south of the church (room B5) and consists of rooms A17–A21 (and possibly A16 and A33, although these are completely filled with sand and their relationship with the surrounding spaces could not be ascertained). The building was accessible only through a doorway set in the north wall of room A19 and opening onto the area in the proximity of the church complex.

Three main passageways defined access to and movement within this sector: one vaulted corridor (B11), running from east to west and dividing area A from the church complex and area B; a narrower north–south corridor (A8) leading from a large, centrally located kitchen (A6) to the vaulted passageway (B11) and therefore to the area of the church complex and the rest of mound I; finally, a long north–south street (A34) in the southeastern part of mound I, separating the main cluster of buildings of area A from the smaller sets of rooms located toward the southeastern edge of the mound (rooms A35–A37 and A38–A40 mentioned above).3

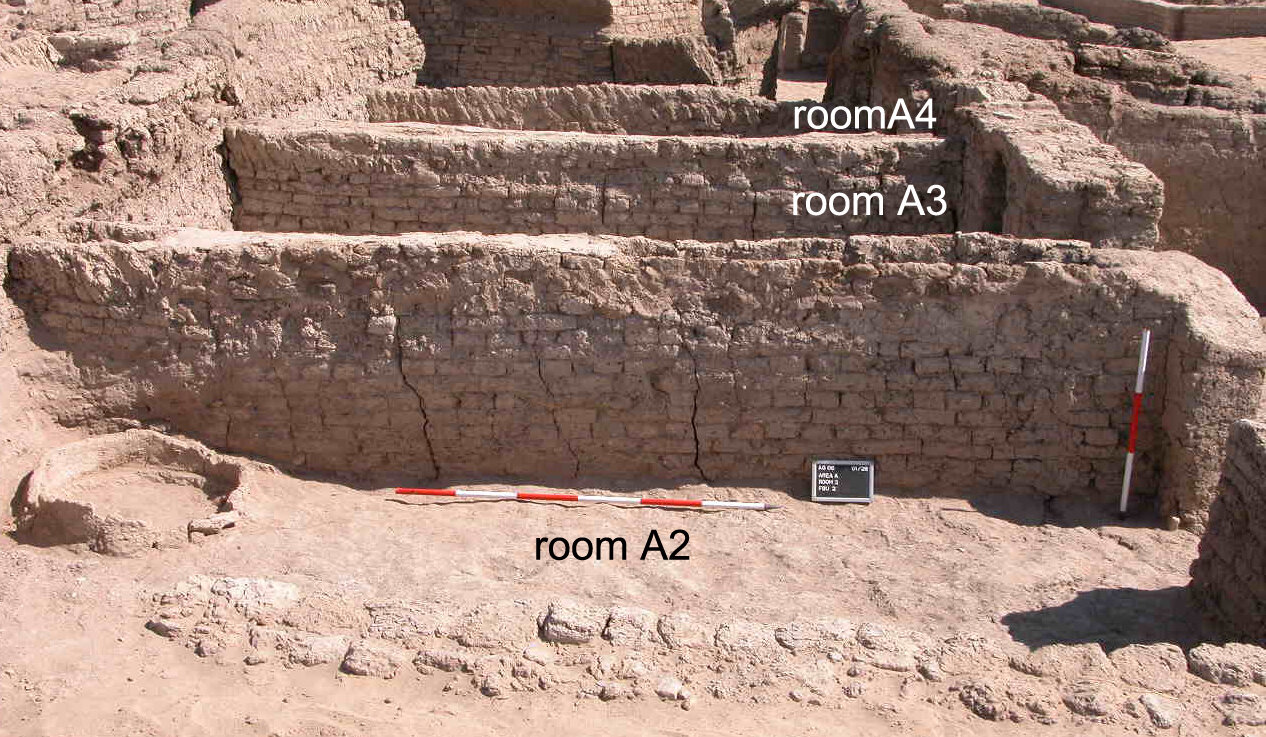

More firmly identifiable as magazines are a set of three rooms (A2–A4) (Plate 2.5).4 The existence of these (and presumably other) fairly large storage areas, their proximity to a wide kitchen centrally located (A6), and the general arrangement of most rooms of area A, forming a network of interconnected spaces, point to their overall utilitarian function and to their use by a community, instead of belonging to separate family households.

As mentioned above, among the several rooms excavated by the Egyptian mission between 1993 and 1995 in area A, a few were selected for their particular architectural interest, in order to create a representative sample. During the 2006 excavation season, they were cleared of the windblown sand that had partially re-filled them and all their architectural features were documented. A discussion of these rooms follows.

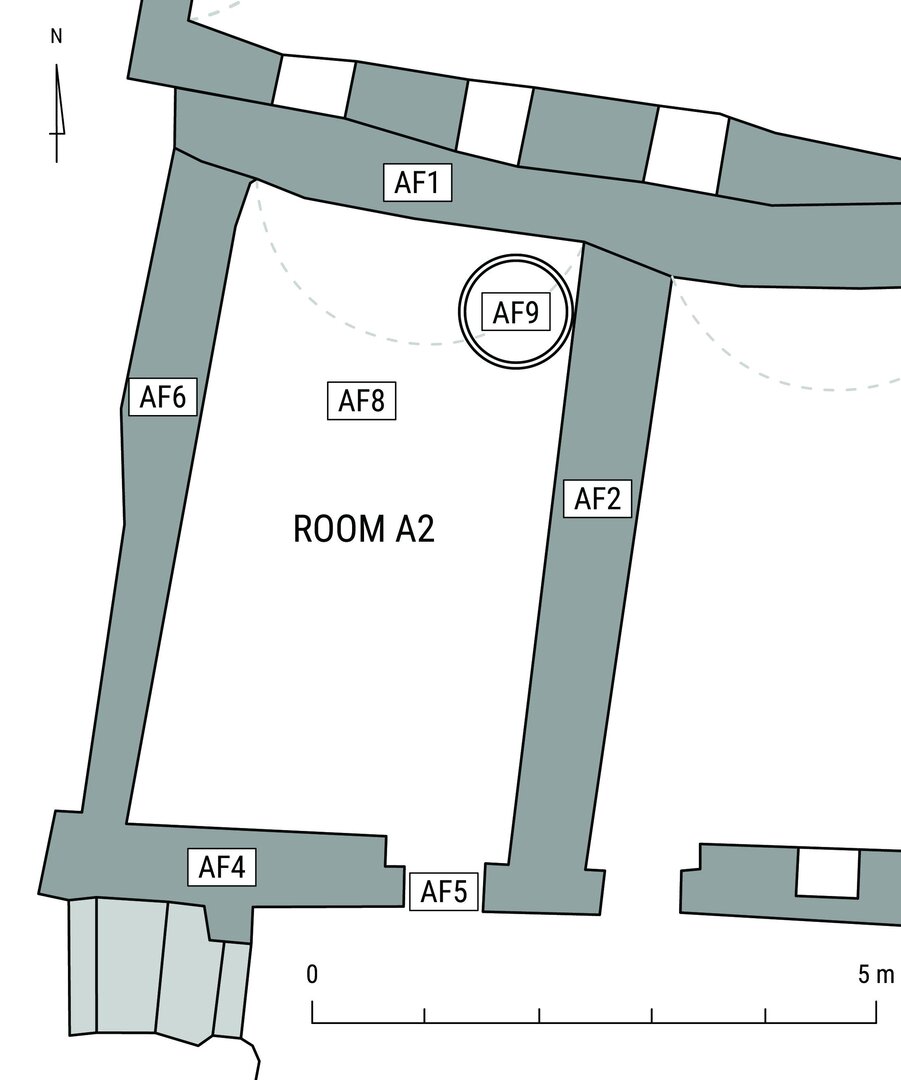

Room A2

Room A2 is located in the southwest corner of mound I. It measures approximately 5.6 m north–south by 3.3 m east–west, with walls that are preserved to a maximum height of 1.42 m (north wall AF1) (Plate 2.3, Plate 2.5, Plate 2.6, Plate 2.7). This space was accessed from a small courtyard through a doorway (AF5; width between the jambs: 0.7 m) placed in the south wall (AF4) toward its east end; remains of a rectangular niche are visible in the middle of the north wall at about 80 cm above gebel. A large basin of unfired clay (AF9), of about 1 m in diameter, is set at floor level in the same corner of the room, surrounded by scanty remains of a beaten clay floor (AF8) (Plate 2.6, Plate 2.7).5 The basin was probably used as a storage bin, as no traces of firing activities were found within or outside this feature, arguing against its identification as an oven or hearth.

Room A2 was originally barrel-vaulted, with the vault springing at a rather low height (about 1.4 m) from the floor, which made the room quite unsuitable for living purposes.6 Indeed, this space is the westernmost of three narrow, rectangular rooms (A2–A4) that may have functioned as small storage areas. These were later additions to the adjacent rooms to the north, as pointed to by the east and west walls (AF2 and AF6 respectively) of room A2 (as well as the east and west walls of room A4) abutting an east–west oriented wall (including AF1 as its westernmost segment) to the north, against which the south wall (AF15) of room A5 was built.

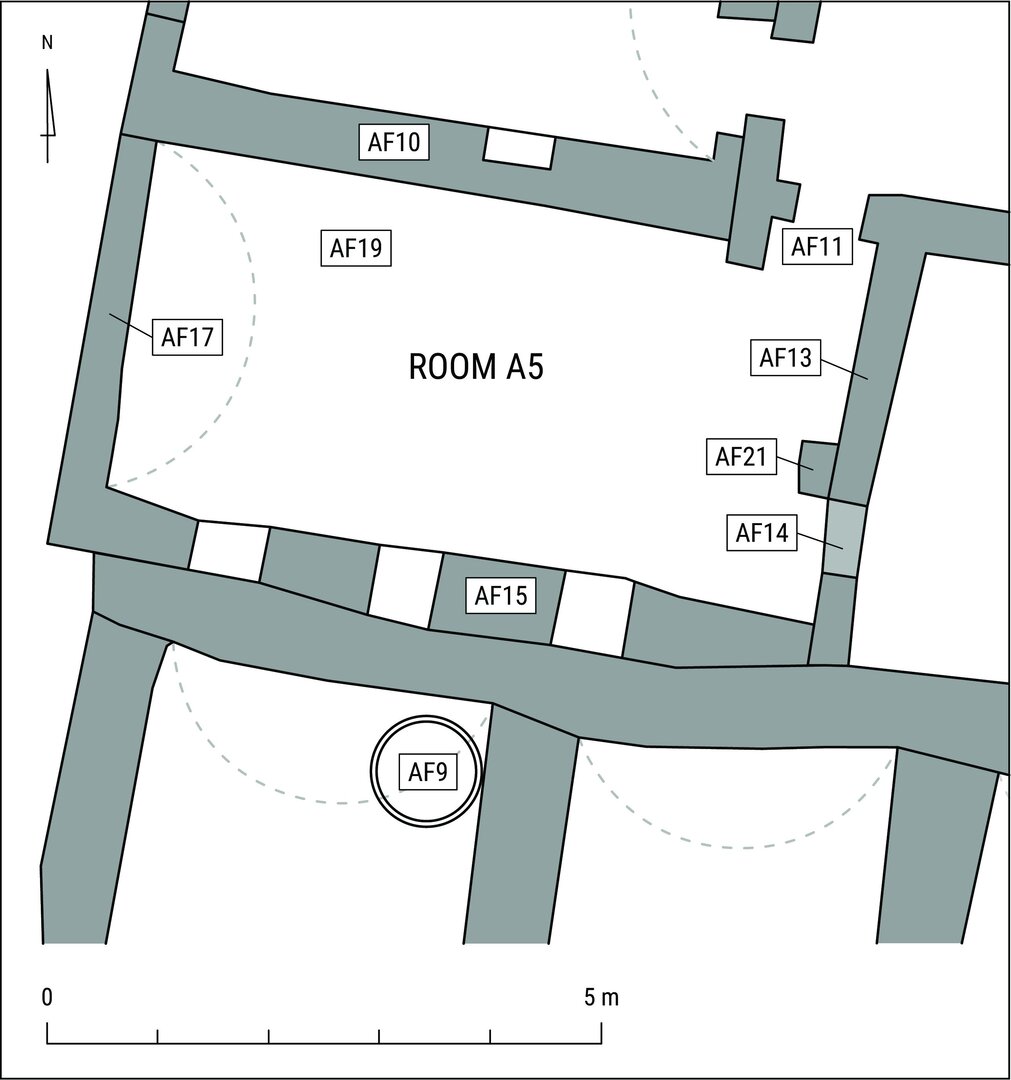

Room A5

Room A5 is located to the north of storage spaces A2–A3 (Plate 2.3). It is a rectangular room, measuring about 3.2 m north–south by 6.5 m east–west, and has mud-brick walls preserved to a maximum height of about 2 m (east wall AF13) (Plate 2.8, Plate 2.9). Originally, two doorways gave access to this space. One doorway (AF14), originally arched, is located at the south end of the east wall and opens onto a large kitchen centrally placed (A6 on the plan of area A). Remains of a stub (AF21) protruding into the room and of the threshold, which has a width of ca. 0.65 m, are still visible, although heavily weathered. The second doorway (AF11), which shows evidence of a stone lintel supported by two protruding jambs, is set at the east end of the north wall (AF10) and leads into room A9 (width between the preserved jambs: ca. 0.6 m).

Vault springs are still partially visible on the long and fairly low (approximate height of 1.4 m) north and south walls.7 Three rectangular niches are inserted in the south wall, set at about 80 cm above ground level. Their width varies between 53 and 59 cm and their average depth is ca. 70 cm. The back wall of the niches is, in fact, wall AF1, running east–west to the south of room A5 and forming the north boundary of room A2.8

The floor of room A5 (AF19),9 quite uneven as it slopes toward the door on the north wall, was found in very poor condition, with only few visible traces of a leveled layer of gray-brown clay. A drain, made with a large fragment of a ceramic vessel (possibly an amphora or a keg), is still partially in situ in the west wall (AF17) of the room, at floor level, set within a north and south facing consisting of stone cobbles (Plate 2.10).

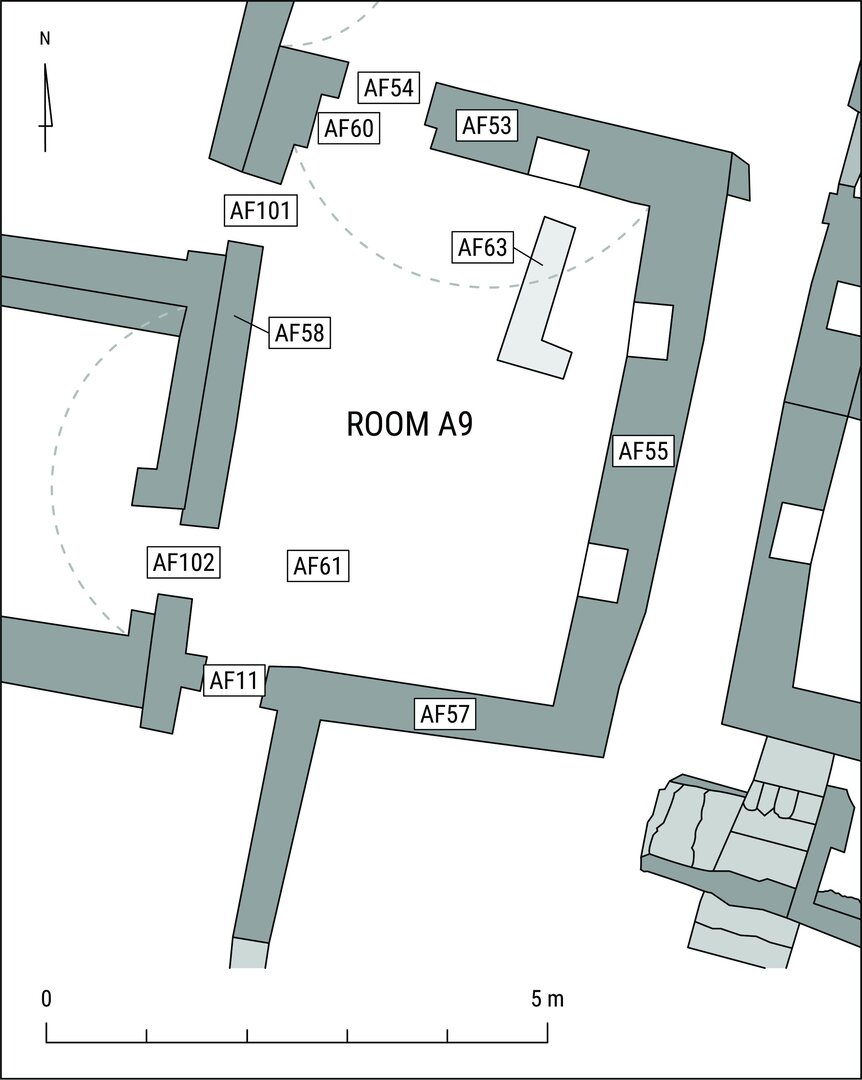

Room A9

Room A9 is a large rectangular space located to the northeast of room A5 (Plate 2.3). It measures 5.25 m north–south by 3.5 m east–west and has mud-brick walls that are preserved to the considerable height of 2.6 m (east end of north wall AF53) (Plate 2.11).

Four doorways open onto this room: one (AF54; width between the jambs: 90 cm) is set at the west end of the north wall and leads into room A13; another (AF101; width: 68 cm) is located at the north end of the west wall (AF58) and was once the only access into square room A11; along the same wall, but further south, is a third doorway (AF102; width: ca. 70 cm), which opens onto room A10; the fourth opening (AF11) is set at the west end of the south wall (AF57) and leads, as seen above, into room A5. The north and south doorways, both defined by side jambs built within, and part of, the same walls, show a higher degree of complexity and craftsmanship than the two doors along the west wall. The latter were, in fact, built within a double wall, consisting of the west wall of room A9 and the east wall of rooms A10–A11, which were seemingly built at a later time than A9.

The room was originally covered by a barrel-vaulted roof. The vault was oriented north–south and is now preserved only in the lowest courses of the vault springs above the east and west walls.10 East wall AF55 rises to a considerable height above the east vault-spring, pointing to the existence, in antiquity, of an upper story.11 The presence of a stairway in room A6, to the southeast of A9, further supports this possibility.

Two roughly square niches, measuring ca. 50 by 50 cm and 37 cm deep, are set into the east wall, at about 1 m above ground level (Plate 2.12). Both are framed by a thick band of white gypsum, as customary in the oasis. The northern niche has a stone lintel still in situ, while the upper part of the southern niche shows signs of heavy damage. Another niche, sharing similar width and depth as the other two but with a recessed round top, is inserted in the north wall, at a distance of about 72 cm from the wall’s east end. It is also framed by a roughly square band of white gypsum.

The original floor (AF61)12 of beaten clay, laid on gebel, is largely missing, with most visible remains located to the north of the doorway opening onto room A5. An L-shaped foundation trench (AF62), filled with a course of mud bricks (AF63), is still visible at ground level in the northeast corner of the room. This feature is presumably associated with an earlier structure, the walls of which were leveled when the compacted mud floor of A9 was laid.

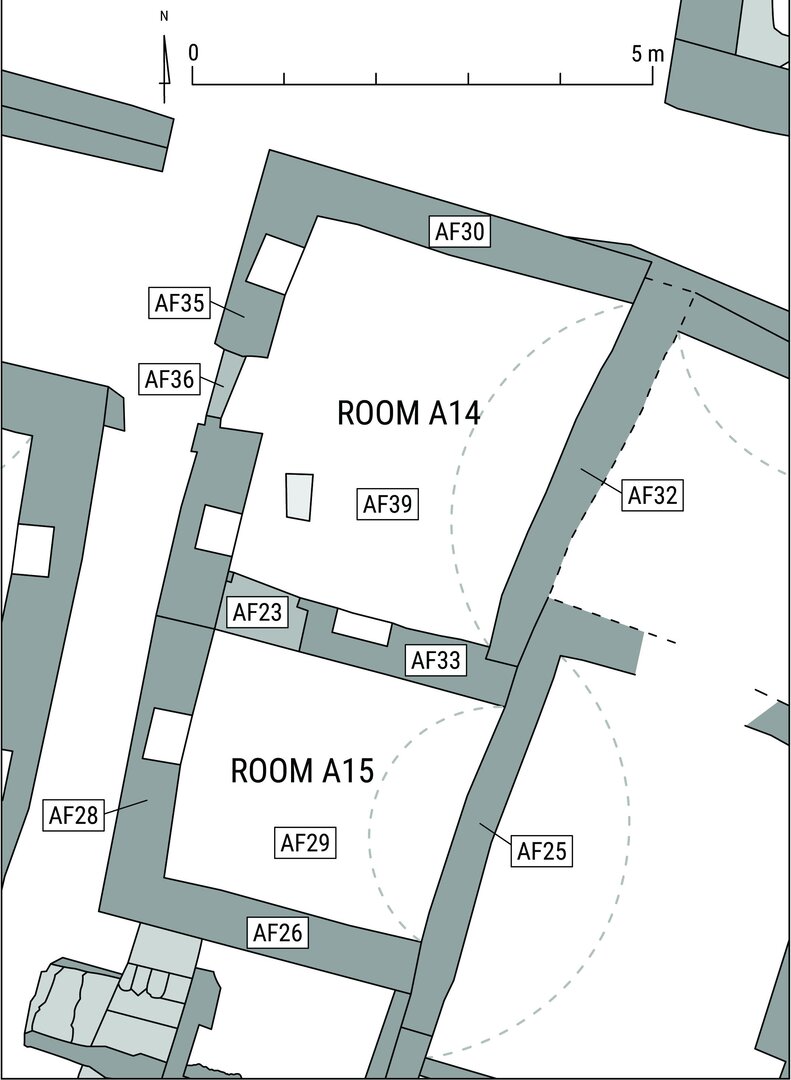

Rooms A14–A15

Two interconnected rooms were cleared in the north part of area A, that is, rooms A14 and A15 (Plate 2.3). A14 is a rectangular space, larger than room A15 and located to the north of it. A14 measures 4 m north–south by 3.5 m east–west, with walls standing up to 2.6 m (east wall AF32) (Plate 2.13). A15 is a roughly square space that measures 2.6 m north–south by 3 m east–west, with walls preserved to the maximum height of about 2.45 m (east wall AF25) (Plate 2.14).

Room A14 is located immediately to the southwest of church B5 and is accessed via a north–south oriented passageway (A8) that connects the area of the church complex to the core of area A, particularly a large kitchen centrally placed in the southern half of mound I (i.e., rooms A6–A7). From A8, one could enter room A14 through a doorway (AF36; width: 74 cm) set in the middle of the room’s west wall (AF35) (Plate 2.15). The remains of the doorway consist of a mud-brick threshold and one protruding jamb built on the south side, which also shows evidence for the placement of a door in antiquity. The sill was found at a considerably higher level than the floor, suggesting that at least a couple of steps once led into the room. Another doorway (AF23; width between the two preserved jambs: 75 cm), located at the west end of the south wall (AF33), allowed passage into room A15. No other door exists in this space, which was therefore accessible only through room A14.

The two spaces were originally barrel-vaulted, with both vaults oriented east–west. Their remains, as well as traces of the mud bricks and potsherds filling the space between the two vaults, are still visible.13 The floors of both rooms (AF3914 in room A14 and AF2915 in room A15), now largely destroyed, consisted of levelled clay, with inclusions of iron pan, laid out on gebel. The cleaning of room A14 revealed a few traces of mud bricks at floor level, placed just south of the west doorway. It was not possible to verify if these mud bricks belonged to an earlier wall that was razed when the floor of room A14 was laid out, although it seems likely.

Room A14 has two arched niches set into the west wall, to the north and south of the doorway, at about 1.3 m above ground. The north niche (width: ca. 55 cm; depth: ca. 45 cm) is framed by a square band of whitewash above mud plaster, while the niche to the south (width: ca. 45 cm; depth: ca. 40 cm) was only covered with mud plaster. The arch framing the top of this niche is slightly recessed into the wall. Another niche (width: ca. 60 cm; depth: ca. 25 cm) is located in the south wall of room A15 at ca. 1 m above ground level. It is architecturally more complex than the other two niches of room A15. It has a roughly round top, but it is set within a slightly recessed square frame, plastered with mud, which has horizontal slots set within its upper and lower edge (possibly for now-disappeared stone or wood elements). Room A15 has only one niche (width: ca. 60 cm; depth: ca. 40 cm). It is placed in the middle of the west wall (AF28), at ca. 1.3 m above ground level. It has a recessed round top and is framed by a thick (about 30 cm) band of white gypsum plaster (now largely disappeared) on top of mud plaster.

Two horizontal recesses, each more than 1 m long and ca. 20 cm deep, run above the two niches in the west wall of room A14, at a height of about 2.40 m above ground level (Plate 2.14). They were both coated with mud plaster. The west wall of room A15 seems to reflect a similar situation, although the two segments of the recess are in poorer condition. The considerable height of these features, which makes them difficult to reach, and their shallow depth make their original function particularly difficult to identify.

Traces of white plaster with three uncial Greek letters [ΗΠΑ], written in dark red ink, were found on the east wall of room A14;16 however, it was impossible to discern the meaning of the inscription or its original extent; even the language (Greek or Coptic) is uncertain (Plate 2.16).

The north and south walls of rooms A14–A15 (i.e., AF30, AF33, and AF26) abut walls to the east (AF32 and AF25) that seem to belong to older buildings and therefore testify to earlier construction phases. Reflecting the pattern of topographical development that was noticed in several other instances in area A, both rooms A14 and A15 reveal the growth of the built environment (more obvious in the southern half of mound I) from a central core of buildings to a larger and more complex network of structures, which reached the outer edges of the mound.

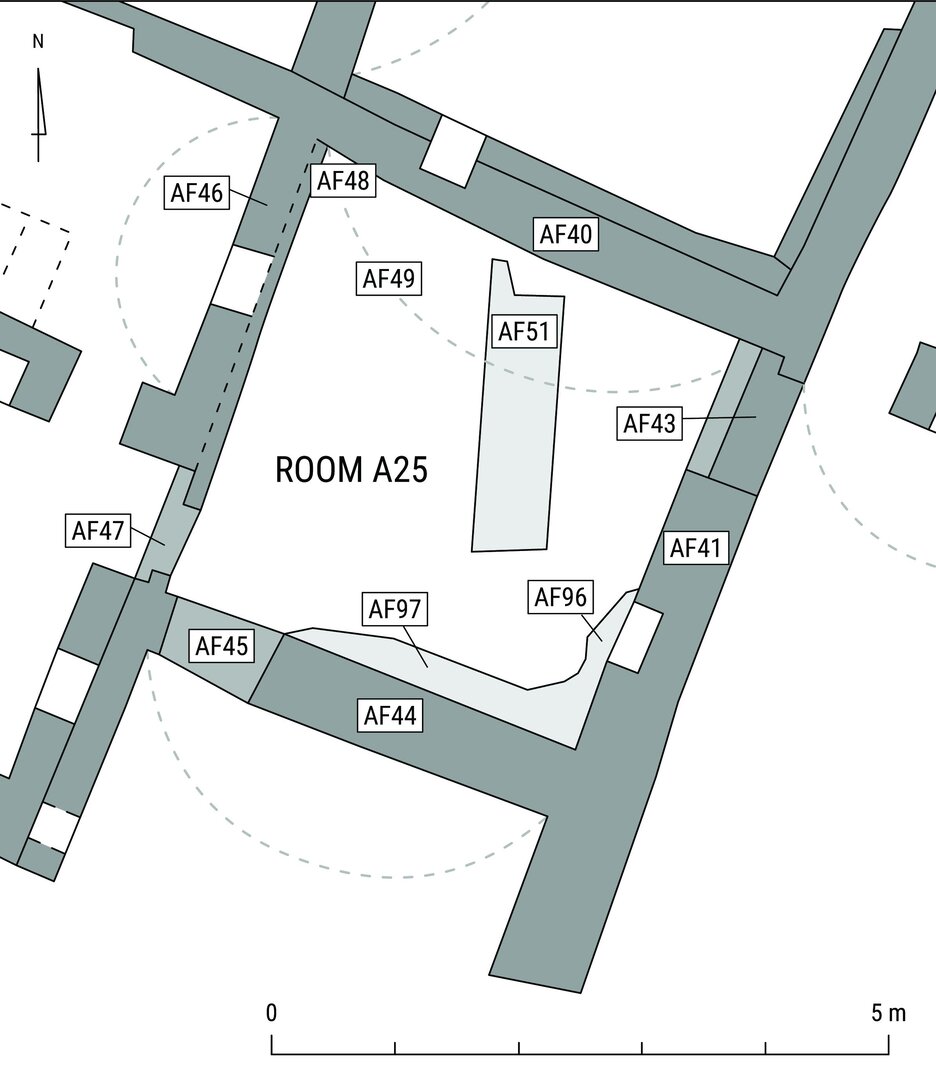

Room A25

Another room, A25, was cleared of sand and recorded in the central part of area A, more to the east (Plate 2.3, Plate 2.17).17 It measures ca. 3.90 m north–south by 3.60 m east–west and the maximum height of its walls is 2.48 m (south wall AF44). The room was once covered by a barrel-vaulted roof oriented north–south; scanty remains of the vault were detected on both the east and west walls.18 The east face of the east wall is substantially higher than the vault spring of room A25, pointing to the existence of a now-lost upper story.

In its latest occupational phase, room A25 was accessed through two doorways. One (AF45), ca. 90 cm wide and still bearing traces of a mud-brick threshold and holes (possibly door sockets), is set at the west end of the south wall and opens onto room A27 to the south. The second opening (AF47; width between the jambs: 60 cm) is placed at the south end of the west wall and leads into room A31. This doorway was heavily restored and rebuilt as an arched passageway in the mid-1990s. Originally, a third doorway (AF43) was set into the east wall at its north end and opened onto room A24 to the east. At some point in antiquity, the opening, which had a considerable width (ca. 1.15 m), was sealed through the construction of a poorly made mud-brick partition wall (AF43), which is recessed by ca. 20 cm compared to the east wall of the room (Plate 2.18).

A niche is set into the east wall, to the south of the bricked-in opening. It has a rectangular shape, with a width of 58 cm and a depth of ca. 25 cm. The niche, whose stone lintel is still in situ, is framed by a poorly preserved rectangular band of whitewash. A ledge, built at about 1.15 m above floor level, runs along the entire width of the south wall. Both the wall and the sill are part of the same construction episode; the function of the latter feature, however, is not known beyond doubt.

Consistent traces of a compacted mud floor (AF49)19 are still visible in the northwest corner of the room; more to the east, the excavation revealed the foundation trench (AF50) and the first course of a wall (AF51, with a maximum preserved length of 2.35 m) precisely oriented north–south, at an angle compared with the northeast–southwest orientation of room A25 and belonging to an earlier building (Plate 2.19).

Other remains of early walls (AF96 and AF97) were found in the southeast corner. They partly run under the east and south walls of the room, following the same orientation, and partly protrude into the room itself, covered by the preparatory layer (DSU1)20 of later floor AF49 (contemporary to the last occupational phase of room A25). One complete oval lamp (inv. 615), several pottery sherds, as well as complete and almost complete vessels (including a small globular flask—inv. 609—and a bowl—inv. 612), were found below this floor level. Their analysis led to a fourth-century dating for the entire assemblage. It is possible that these vessels and sherds had been deposited there to flatten the uneven geological surface (including the remains of earlier architectural features) before the floor was laid out. Two heavily worn bronze coins were also brought to light within this fill: one (inv. 503) is dated to 313, while the other (inv. 504) was minted between 315 and 318. The general surface clearance of the room revealed two additional bronze coins (inv. 501, dated to 324, and inv. 502, minted in 326), as well as three ostraka (one in Coptic and two in Greek). One (inv. 10) is an account of donkeyloads in four lines, while the other two (inv. 8 and 17) are incomplete and of unclear content.21 Based on palaeographic evidence, the three ostraka are dated to the fourth century, in line with the information provided by coins and ceramics.

Rooms A6–A7

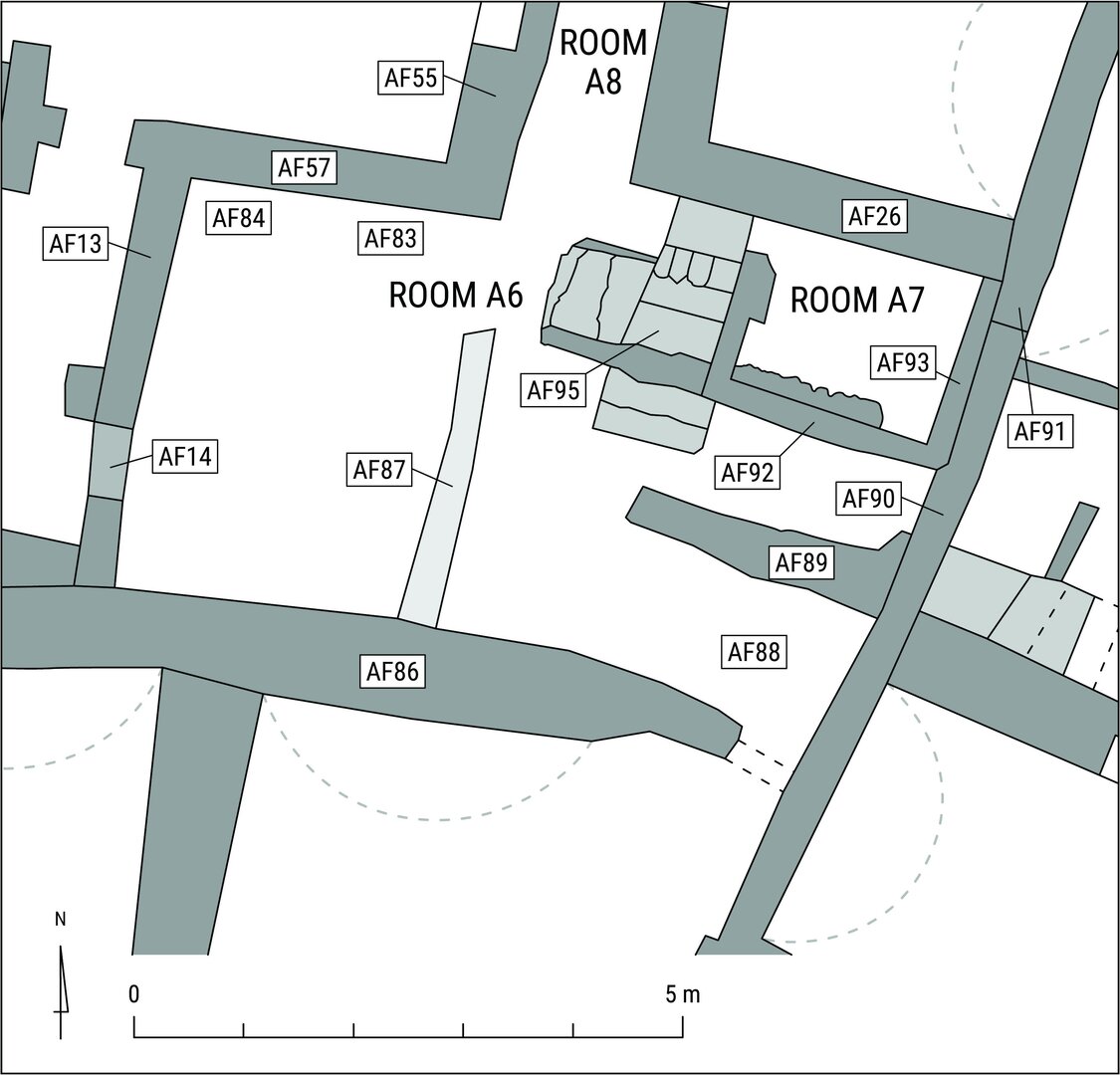

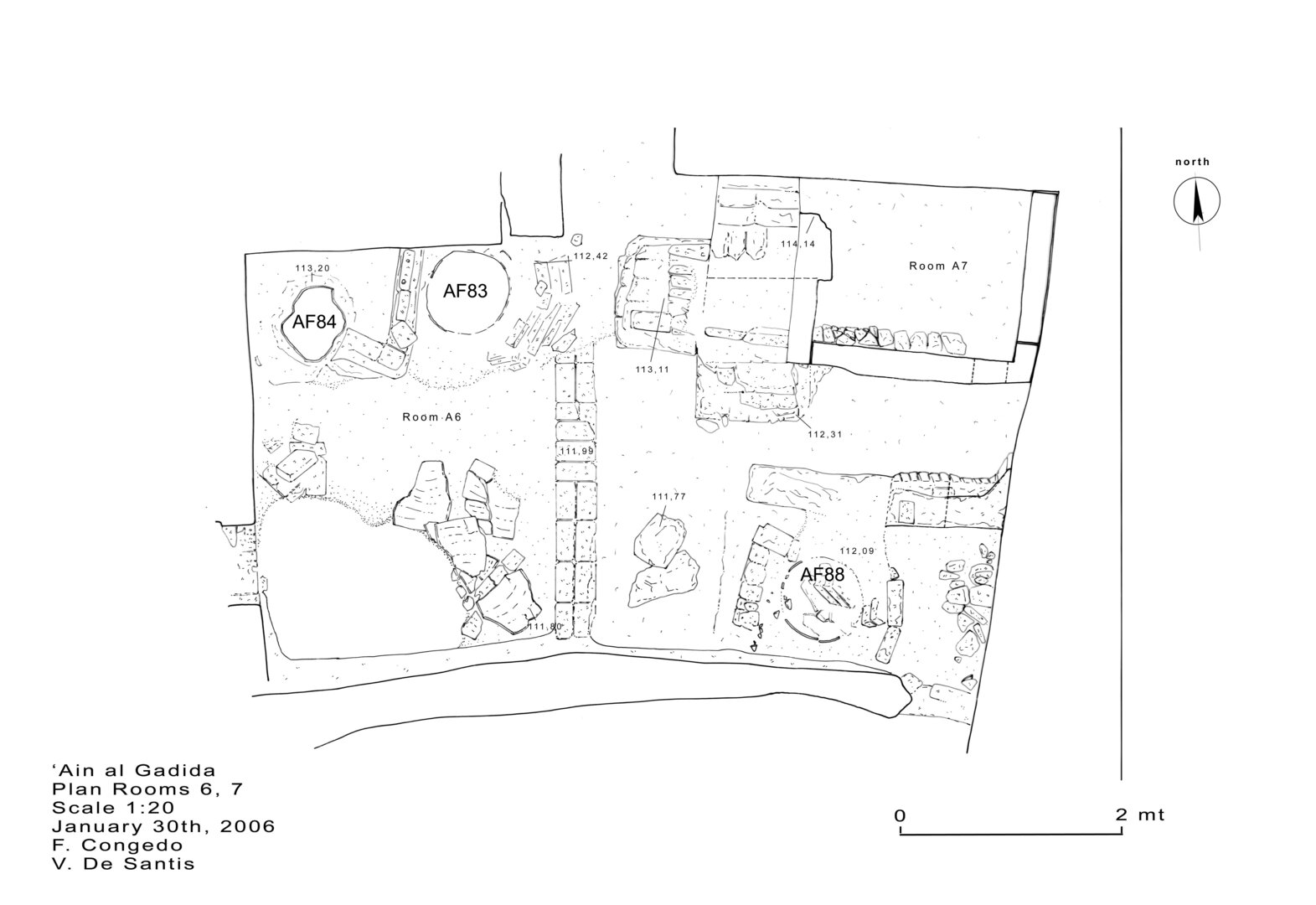

A significant effort was made, in 2006 and 2007, to fully document room A6 and the adjacent space A7, centrally placed in the southern half of mound I—slightly to the west—and to the northeast of the three narrow rooms (A2–A4) preliminarily identified as magazines (Plate 2.3, Plate 2.20). The location of rooms A6–A7, their dimensions, and their wealth of architectural features and installations make these spaces a meaningful case-study.

Room A6 was partially excavated by the Egyptian team in the 1990s and is identifiable beyond doubt as a kitchen.22 It is a rectangular space, measuring about 4 m north–south by 7 m east–west, and has walls preserved to a maximum height of ca. 2.20 m (in its northeast corner, wall AF91) (Pl. 2. 21). The room was once accessible through two main doorways. One opening, ca. 1.05 m wide, is set between the northwest and the northeast walls (AF57 and AF26 respectively) and opens on a long, narrow passage oriented north–south (A8), which in turns leads to a passageway (B11) running northwest–southeast to the area of the church complex.23 The other doorway (AF14) is located at the south end of the west wall (AF13) and, as discussed above, gives access to room A5. A third, narrow passage exists at the east end of the south wall (AF86). It is 58 cm wide and opens onto a very narrow space (A29), against whose walls numerous traces of ash were detected. This space might have been used, perhaps, as a dump for the ash cleared from at least some of the ovens found in room A6.

At the time of its investigation, the floor level was not identified within the room, as it seemed to have suffered heavy disturbances.24

The scanty remains of a low mud-brick wall (AF87), running north–south and parallel to the west wall of the room, cut A6 roughly in half. Its original function is unknown. Among the visible courses of this wall, which was laid out in English bond, a bricked-in section was noticed, about 140 cm wide, which seems to have belonged to an earlier opening that was sealed at some point in antiquity. This wall once abutted the south wall of room A6, although today the latter is slightly slanted toward the south and thus detached from the former.

A staircase (AF95) is set against the northeast wall. It was originally built above a stratified deposit of many thin layers rich in ceramic and organic inclusions (Plate 2.22). The upper section of the stairway is oriented north–south and is supported by a north–south wall and a vault built with mud bricks laid out as stretchers on edge. Above the vault are four stone steps embedded in mud mortar. The staircase continues with a lower section that is oriented east–west and consists of three (remaining) steps.

The available archaeological evidence suggests that originally the staircase was built just as one flight of steps oriented north–south. Indeed, to the south of the deposit supporting the upper section of the staircase, and projecting from it, is a mud-brick rectangular feature that may be the poorly preserved remains of the lowest part of the original stairway. A second construction episode involved the addition of the east–west flight of steps, whose lowest end is almost completely missing. The result was a staircase running, in its upper section, north–south and then turning clockwise, obstructing almost completely the passage into corridor A8. This testifies to the fact that, during at least the latest phase of occupation of room A6, the doorway/ passage into A8 was no longer in use.

To the east of the stairway, two partition walls were constructed with a very poor construction technique: one (AF92) running east–west from the staircase and the other (AF93) set against the north sector of the kitchen’s east wall (AF90, with the southern end of AF91 in the northeast corner). A secondary room (A7, measuring ca. 1.60 m north–south by 2.10 m east–west) was thus created against the northeast corner of A6, separate from the kitchen and accessible only through the vault supporting the highest ramp of steps (and built in phase with the staircase).25

The high walls of room A6, all showing rather poor and hurried craftsmanship, bear no trace of vault springs or sockets for the placement of beams supporting a flat roof. Either the roof and the highest courses of the walls collapsed, leaving no sign of its original existence, or this space was actually an open courtyard, as one might surmise from the very poor craftsmanship of many of its walls and the rather central placement of the staircase. The possible absence of a roof is also suggested by the existence of at least three ovens built at some point here (Plate 2.23, Plate 2.24).

Two circular bread ovens (AF83 and AF84) are located in the northwest sector of the kitchen; one is still partially in situ, while the other lies to the south of its original location; it fell in 2005, probably as a result of the collapse of part of the staircase to the east.26 The former appears to belong to the “Later Type” of ovens, following S. Yeivin’s classification, or “Type II-Subtype a”, according to D. D. E. Depraetere: that is to say, a circular ceramic oven, built on a raised earth platform and surrounded by mud-brick partition walls.27 Parts of another round oven (AF88) were found in situ in the southeast sector of the kitchen. Behind AF88 are the remains of a long rectangular installation (AF89), which consists of a wall and part of a vault. A circular opening, measuring ca. 55 cm in width, cuts through the wall from north to south. The original shape and function of this installation is unknown.28

The archaeological evidence shows that room A6 went through several construction phases, which involved most walls of the room and the staircase. As mentioned above, room A6 was located in a rather central position and led, through a narrow passageway (A8)—at least before the latter was blocked by the lower end of the staircase—to an area in the proximity of the church. The dimensions of the kitchen and the presence of at least three ovens suggest that the facility served a fairly large group of people, although they do not shed light on who these people were.

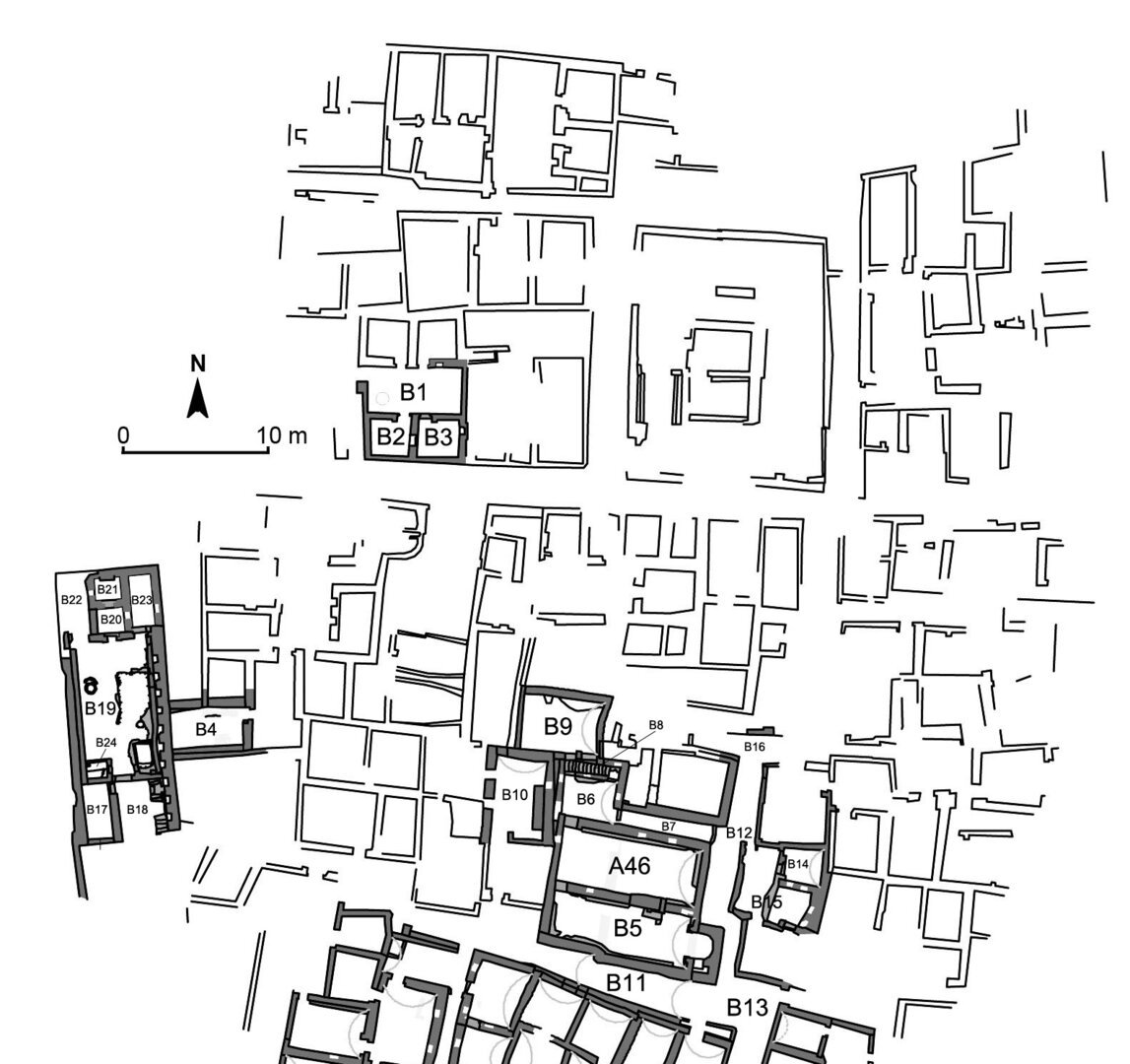

2.1.2 Area B

Before the beginning of excavations in 2006, a systematic surface clearance of mound I revealed a network of several buildings, various in size and often interconnected, extending throughout most of area B (Plate 2.25). Although the layout of area B gives the impression of a rather confused arrangement of space, traces of more regular planning can be easily identified (Plate 2.26). A network of perpendicular streets, dividing the northernmost part of the hill into quadrants, can be detected to a certain extent. Sets of interconnected rooms (unexcavated), sometimes opening onto spaces that seem to have been inner courtyards, were built against each other to form larger, roughly rectangular blocks divided by the streets. Rooms B1–B3, investigated as a test trench in 2006, reflect a similar spatial arrangement, although with additional rooms.

The results of archaeological investigation in this area (concerning, in particular, rooms B1–B3) point to its identification as a possible residential area, with the smaller groups of rooms-plus-courtyard as domestic units. The southern part of area B, especially the sector occupied by the church complex and the spaces adjacent to it, reflects a more irregular layout. However, this might be due, at least in part, to the substantial and multi-phased rearrangement of space that involved the area of the church complex, as proved by its archaeological investigation.

A remarkably large structure, rectangular in shape, lies toward the northern edge of mound I (Plate 2.27). Although it was not excavated, its outline was partially visible above ground level. It consists of two rectangular rooms measuring ca. 3 m north–south by 4 m east–west and sharing one of the longer walls. It was not possible to determine, without excavation, if they were originally interconnected. The two rooms are located at the center of a wide, rectangular structure measuring ca. 16 m north–south by 12 m east–west.

The state of preservation of these walls seems to be rather poor, and parts of their outline could not be mapped during the survey. This does not imply that the missing wall segments (especially in the middle of the south side and toward the northern end of the west side) indicate the precise location of doorways into the complex; indeed, the walls might simply be preserved at a lower level in those points. Only a thorough archaeological investigation could shed light on the building’s outline, the interrelationship of its architectural features, and the precise location of its entrance/entrances. A preliminary analysis of the available evidence suggests an identification of the complex as a pigeon tower, surrounded by a large rectangular courtyard.29 Pigeon towers were a typical feature of the oasis landscape in Roman times and during Late Antiquity, as shown by the D.O.P. survey of ancient farmhouses and villages of Dakhla.30 In particular, the remains of a columbarium were discovered and investigated in recent years by Colin Hope at the site of Kellis, not far from ʿAin el-Gedida.31 Located within an open area in the northern part of the site, and possibly associated with a group of three large residences to the east and southeast, this pigeon tower consists of two adjoining structures of rectangular shape and similar dimensions, each of them further divided into two roughly equal rooms. Considerable ceramic evidence was collected of pigeon nesting jars, once set into the upper walls of the tower. The overall layout of the Kellis columbarium closely resembles that from ʿAin el-Gedida, although the former is of a substantially bigger size.32

Ten meters west of the pigeon tower, three rooms (B1–B3) were identified as part of a larger structure that included two additional rooms and that was possibly identified as a residential unit. Test trenches were conducted in this area and involved the excavation of rooms B1–B3. Another room (B4) was chosen and excavated, as part of preliminary test trenching, to the southwest of rooms B1–B3. During the investigation, remains of earlier walls were brought to light, suggesting that the room, as well as the building of which it was part, underwent substantial modifications. The room was used as a domestic midden in its latest phase.33

To the west of room B4, a large complex of eight rooms (B17–B24), uncovered in 2008, lies along the western edge of the mound, only a few meters away from the cultivated fields. An examination of the walls and their relative chronology points to different construction phases for the complex. The archaeological evidence allowed the identification of the complex as a ceramic workshop, built reusing features that comparative analysis allowed us to recognize as part of an earlier mud-brick temple.34

About twenty-five meters to the southeast of rooms B17–B24, and immediately to the north of area A, lies the complex excavated between 2006 and 2007.35 It consists of a church (B5), a large gathering hall (A46), two rooms (B6, B9), an entrance/passageway (B7), and a staircase (B8), all developing to the north of the church. An additional room (B10), identified as a kitchen, was excavated immediately to the west of room A46, although not connected directly with the church complex.

Two more sectors, along the southern and eastern ends of the church complex, were investigated in 2008. They include an east–west passageway (B11), a north–south street (B12), a crossroad (B13), a kitchen and a pantry (rooms B14–B15). The discussion of the archaeological remains pertaining to the church and its neighboring rooms will be the subject of chapters 3–5.

Notwithstanding the intense work carried out between 2006 and 2008, especially in the area of the church complex, a large number of buildings remain unexcavated in area B. Therefore, discerning the general architectural layout of this part of the site and identifying the possible phases of its development are a very complex matter. The site plan, created with the data obtained during the topographical survey, offers several pieces of information. However, a simple reading of walls that are visible only at their higher end, without their proper and complete excavation, can be misleading in terms of the interpretation of their architectural relationship with each other. In fact, the depth of preservation of most features often makes doorways difficult, if not impossible, to identify, because the walls above their lintels are not readily distinguishable from other parts of the walls. As a consequence, it is not sufficient to shed light on the construction process of the buildings surveyed at ground level. Nonetheless, a great deal of information was collected during the excavation of large sectors of this part of mound I, considerably adding to the understanding of ʿAin el-Gedida’s typology of buildings, construction techniques, phases of expansion, and overall development of the site.

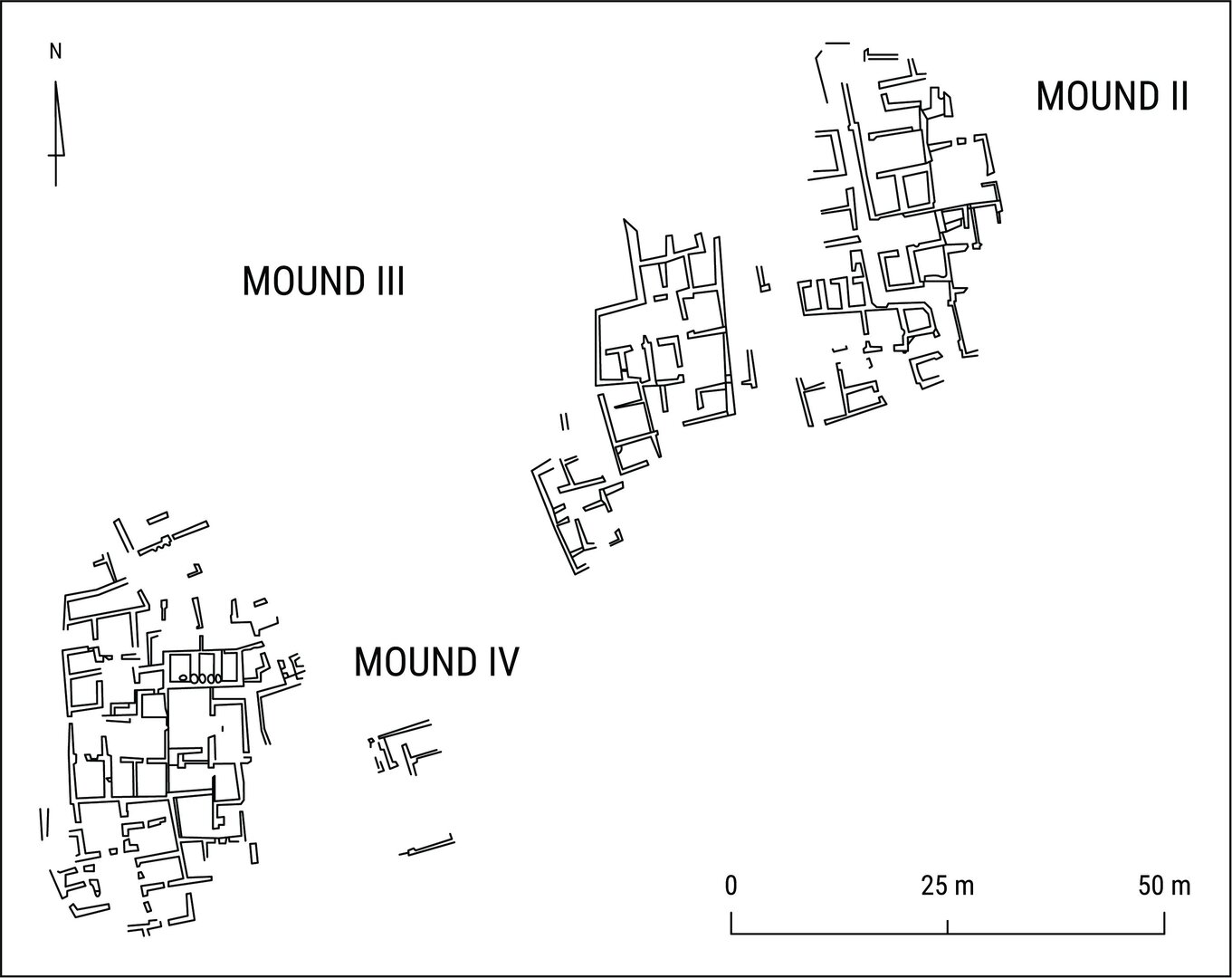

2.2 Mounds II-V

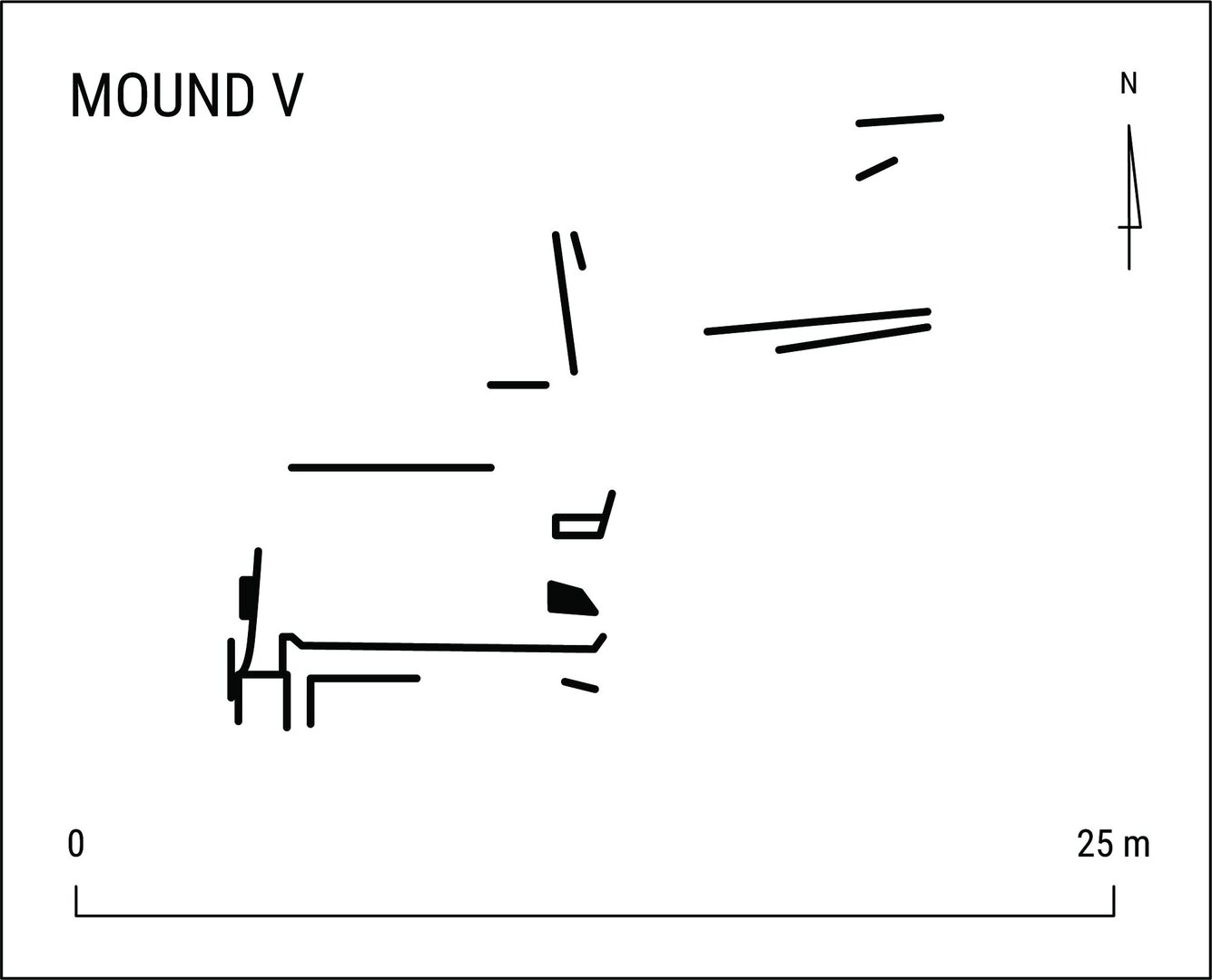

Excavations were not carried out on mounds II-IV, located to the south of the main hill, or on mound V, a few hundred meters to the northeast of mound I, where the visible remains of architectural features are rather limited. Nonetheless, a topographical survey was carried out on all mounds in 2006–2007 and, once again, in 2010, when additional surface clearance allowed for the gathering of further architectural details (Plate 2.28).

The survey of mound II revealed the existence of several mud-brick buildings and of a street oriented northwest–southeast. The visible remains of this street consist (from north to south) of a long (about 30 m) passage running northwest–southeast, joined to the south to a segment running to the east for ca. 8 m; then the street continues with a third sector following, for about 10 m, the same northwest–southeast orientation as the northern segment, until it gets lost under the sand (Plate 2.29).

All structures, in most cases completely filled with windblown sand, are built along this passageway and show a rather compact and complex organization of space, following a pattern already identified on mound I. In particular, a set of three rectangular rooms parallel and built next to each other, with the long side oriented north–south, were noticed in the southwest sector of the mound; these spaces show an arrangement that is reminiscent of that of rooms A2–A4 in the southern part of mound I, identified as storage rooms.

Two clusters of rooms were found to the northeast of the above-mentioned street. They consist of two, roughly square rooms flanking (with at least one of them opening onto) a larger rectangular space. This building (or part of it) has a shape that is suggestive of rooms B1–B3 investigated in the north half of mound I and of rooms A35–A37 (and possibly A38–A40) partially excavated in the southern half of mound I in the mid-1990s.

The construction technique and the material of the architectural features surveyed on mound II (mostly walls laid in English bond, with gray-brown mud bricks of standard size and rich in organic inclusions), seems to be quite similar to those investigated on the main hill.

At the time of the topographical survey, only a few remains of mud-brick buildings were identified on mound III above ground level (Plate 2.28, Plate 2.30). They consist of two clusters of interconnected rooms, the larger only a few meters to the west of mound II and the smaller located further to the southwest. Most of the visible architectural features follow the same north–south orientation as found on mound II and share the same materials and construction techniques. In light of the close proximity of the two mounds and of their archaeological remains, it seems that the buildings on both hills were, in fact, one large built-up area.

Mound IV, like mounds II-III, is closely surrounded by cultivated fields, which have been encroaching upon the archaeological remains. The topographical survey revealed how several architectural features had already disappeared due to the extensive crop growing, while others were in danger of being permanently erased by the seemingly expanding agricultural exploitation of the area. Notwithstanding, several structures were mapped on this mound (Plate 2.28, Plate 2.31).

As was the case for all the rooms surveyed on neighboring mounds II-III, most spaces were found almost completely filled with sand.36 However, the preserved tops of their often mudplastered walls revealed a tight and complex network of rooms, in a few instances clustered around, or opening onto, larger rectangular spaces. A set of three narrow rooms, oriented north–south and with well-preserved remains of barrel-vaulted roofs, is located in the northeast part of the mound. These rooms reflect an arrangement that is similar to other sets of spaces located on mounds I (area A) and II; they possibly were used in antiquity as magazines for crops. No buildings with a complete and clearly defined layout could be discerned on mound IV; thus, any typological study of its architectural remains is not possible without further, in-depth archaeological investigation.

The topographical survey did not reveal significant traces of the streets or passageways once running on the mound. However, it showed that the orientation of the rooms is, once again, similar to that followed by most buildings on mounds II and III. It is not known, although is certainly possible, if the buildings located on mound IV were once part of the same built-in area extending throughout mounds II-IV and perhaps also continuing to the north onto mound I.

Mound V lies to the northeast of the main hill of ʿAin el-Gedida, outside the protected archaeological area (Plate 2.28, Plate 2.32, Plate 2.33). Heavy disturbances, connected with the agricultural exploitation of the surrounding land, have occurred (and continue to take place) on this mound. As a consequence, the very few remains of architectural features that are visible above ground are in extremely poor condition.

The survey identified and recorded scanty traces of mud-brick walls that likely belong to two rectangular structures, roughly oriented east–west. The southernmost of these two rooms has its long south wall preserved to a length of about 8.5 m and bears traces of a smaller space built inside, presumably placed against the east wall (now missing or standing at a lower elevation beneath the sand). The smaller room seems to have been built at the east end of the main axis of the rectangular space and once opened onto it through a doorway (width between the jambs: ca. 1.15 m) placed along its west wall. It was impossible to map the full outline of this structure, or that of the other room to the northeast, due to their extremely poor state of preservation. No serious attempt in reconstructing the original layout of these spaces, as well as identifying their function, can be carried out without their full archaeological investigation.

It should be added that, according to Kamel Bayoumi, who led the Egyptian mission at ʿAin el-Gedida in the mid-1990s, local farmers found several human bones while digging in the area of mound V in recent years. This fact led him to tentatively identify this mound as a cemetery in connection with the main site.37 No human bones were found during the topographical survey of the area;38 however, only in-depth excavations would allow us to gather more information regarding the relation of mound V to the site and its use in Late Antiquity.

2.3 Test Trenches on Mound I

In 2006, the topographical survey of ʿAin el-Gedida was paired with preliminary excavation activity in the northern half of mound I. In order to gather additional data on the underexcavated (by 2006) area B, two small areas were selected for archaeological investigation, one in the northwest sector of the hill (rooms B1–B3) and another a few meters to the southwest (room B4), in the proximity of the western complex excavated two years later.

2.3.1 Rooms B1–B3

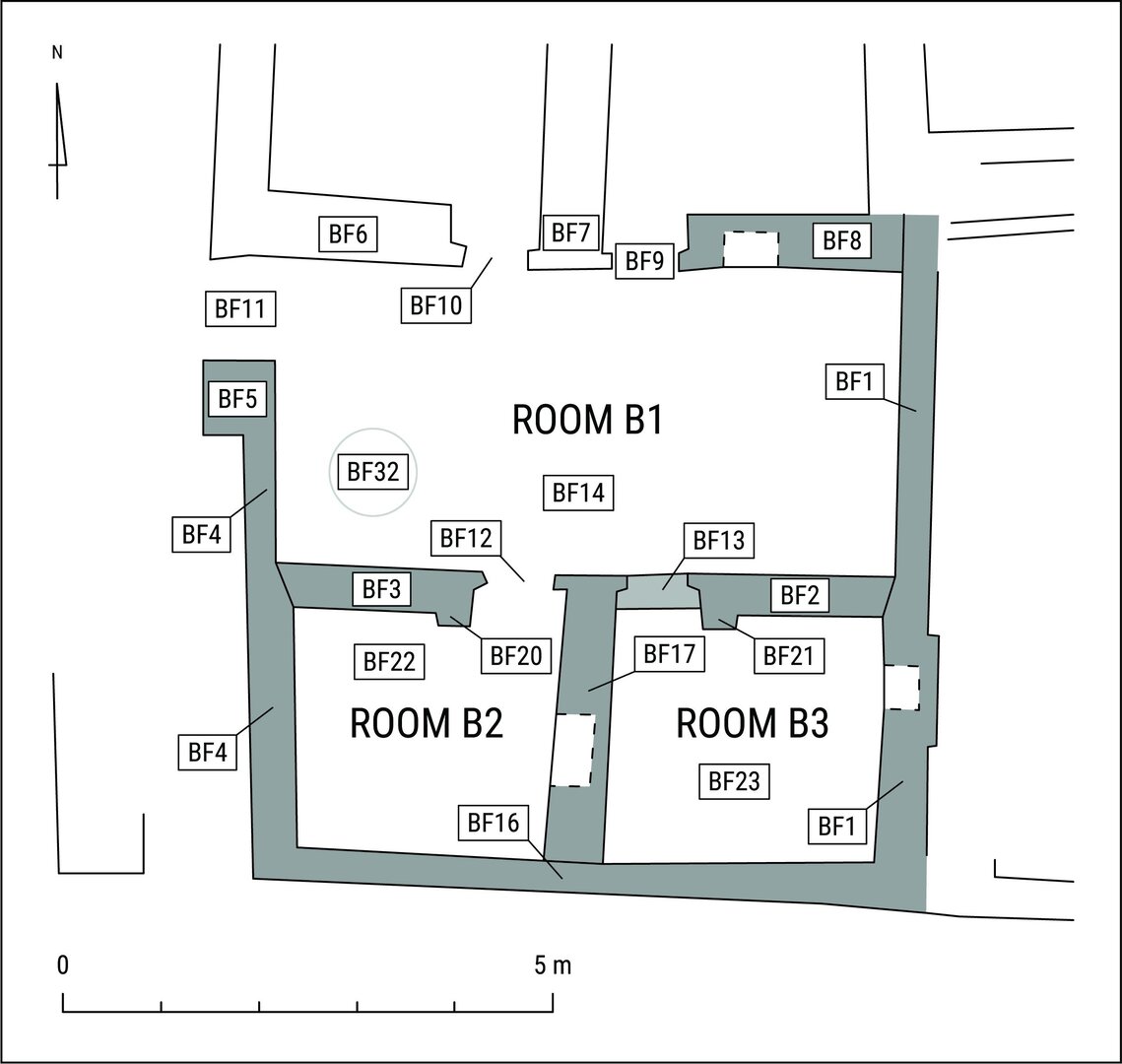

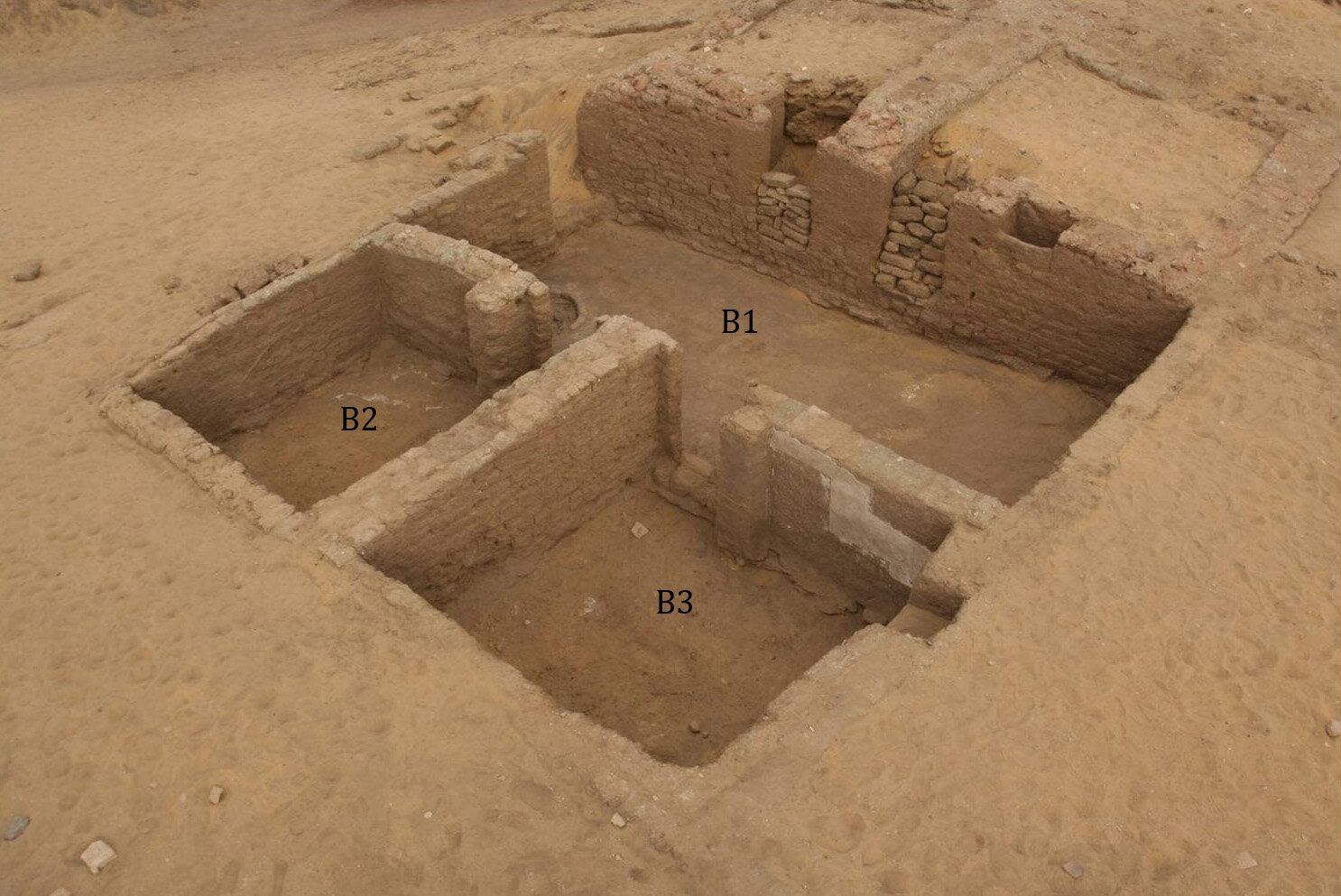

Rooms B1–B3 are located a few meters to the west of the large structure identified (preliminarily) as a pigeon tower and discussed earlier (Plate 2.26, Plate 2.34, Plate 2.35). The excavation of these rooms to floor level (or gebel), paired with an accurate surface clearance of the surrounding area, allowed the identification of the three rooms as part of a larger building extending further to the north. The overall layout reveals a regular and well-planned arrangement of space, with a large rectangular room (B1, oriented east–west) that opens, to the north and to the south, onto two sets of roughly square rooms symmetrically placed; B2–B3 are the two rooms built to the south of room B1. Due to time constraints, it was not possible to investigate the two spaces to the north.

The size of the three investigated spaces is ca. 42 m2, while the entire area of the building, including the two rooms to the north, is about 64 m2.

B1 is a rectangular room measuring 3.15 m north–south by 6.45 m east–west. The mudbrick walls, which are preserved to a maximum height of ca. 1.80 m (west half of the north wall BF6), were originally coated with mud plaster. The room, and the rest of the building to which it belongs, was once accessible from the outside through a doorway (BF11; width: 109 cm) located at the northwestern corner.

Bonded walls BF4 and BF5 form the western boundary of room B1, while BF1 is its east wall. The north side is defined by three different walls (BF6–BF8, the last abutting BF1) and two doorways (BF10 and BF9).39 The lower rectangular half of a niche (56 cm wide and 37 cm deep) is preserved in the east half of the room’s north side (BF8).40 The remains of the niche show evidence of alterations carried out in antiquity, such as a low, narrow barrier poorly built to partially seal the bottom of the niche.

The south boundary of the room reflects an arrangement similar to that of the north side and consists of three walls (BF2, BF3, and BF17 in between) separated by two doorways (BF12 and BF13).41

A clay floor (BF14)42 was uncovered in rather good condition throughout most of the room (Plate 2.36).43 A roughly circular hearth (BF32; diameter: ca. 90 cm) was found, in very good condition, in the southwestern corner of the room, set into the floor and surrounded by low edges of clay. A high quantity of ash, charcoal, and seeds were found inside the fireplace, whose presence points to the use of room B1 as a courtyard with utilitarian functions, such as the preparation of food.

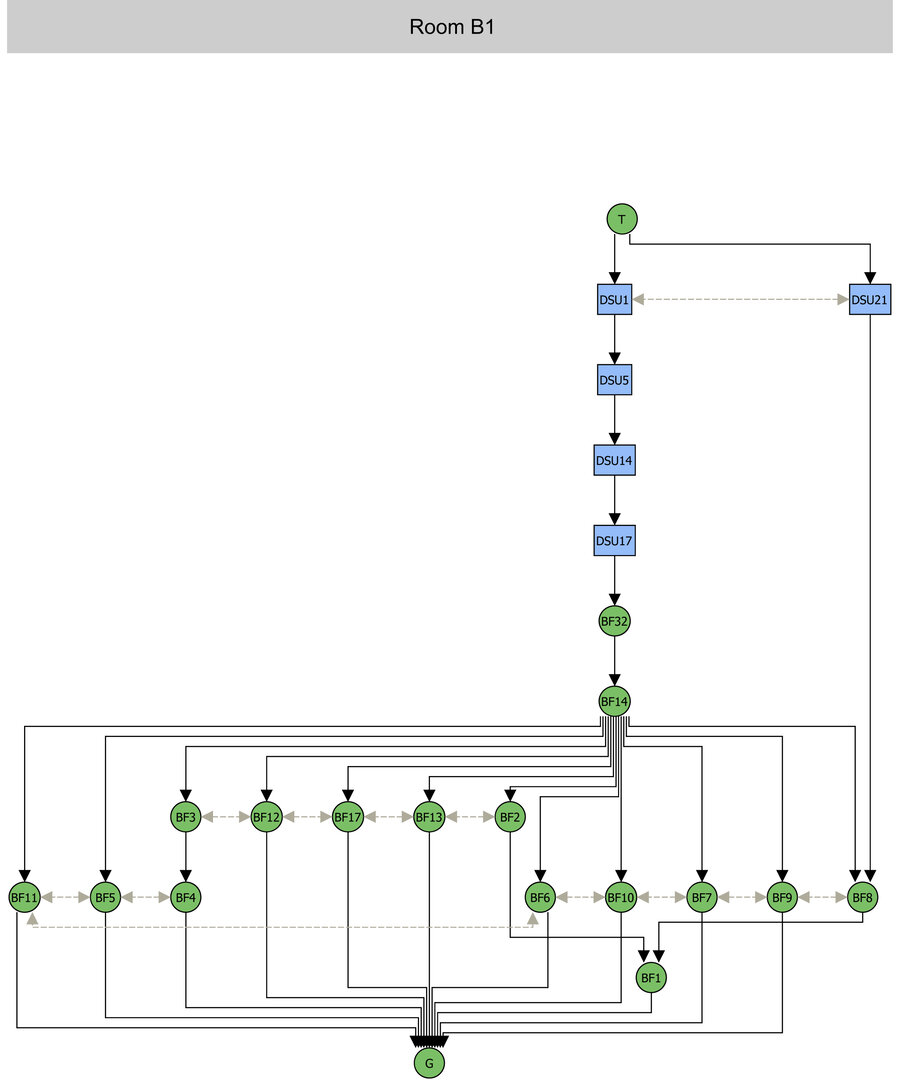

The excavation of this space led to the identification of three main depositional units, all extending throughout the room (Plate 2.37).44 The surface layer (DSU1)45 consisted of windblown sand and a few ceramic inclusions (0.50 kg) and covered a unit of sand (DSU5),46 which was very similar to the unit above but cleaner and less disturbed. A large quantity of ceramic sherds (70.09 kg) was found, although in a relatively low concentration when considering the average thickness of the unit (91 cm). Underneath this unit was DSU14,47 an occupational level mixed with wall and roof debris (Plate 2.38). DSU14 consisted of a thick layer of brown soil, with lenses of yellow sand (particularly in the middle of the room), and rich in organic inclusions, mudbrick debris (from wall collapse), and mud plaster with imprints of palm ribs (likely from a flat roof once covering the room). A high concentration of pottery sherds (51.56 kg) was gathered during the excavation of this unit. Among the vessels that could be reconstructed, partially or almost completely, were a sieve, a keg, storage jars, and several bowls, representing a valuable example of a fourth-century ceramic assemblage of a domestic, utilitarian nature.48 The fourth-century chronological range provided by ceramics for this context is supported by a Greek ostrakon in four lines (a receipt for chickens) found within the same unit (inv. 25). Based on palaeography and the indictional date mentioned in the text, the ostrakon was securely dated to the fourth century. The sand filling the niche that was set in the east half of the north wall was excavated as a separate unit (DSU21).49 It consisted of windblown sand with some mudbrick debris (possibly from the collapsed top of the niche) and contained a few pieces of white gypsum plaster and only two pottery sherds (0.08 kg). A fourth-century Greek ostrakon (inv. 28), a receipt, probably for wheat, in seven lines, was embedded in the preserved lower half of the niche.

The hearth (BF32) placed in the southwest corner of room B1 had a filling (DSU17,50 below DSU14) of moderately compact gray ash, with charcoal and ceramic inclusions (0.24 kg).

Room B1 opens, along the west half of its south side, onto room B2, which measures ca. 2.50 by 2.50 m. The mud-brick walls, preserved to a maximum height of 1.35 m (north wall BF3), are coated with mud plaster. Access to this room was through a doorway (BF12; width between the jambs: 70 cm) located at the eastern end of the north wall. The two jambs and a stub (BF20, perpendicular to the north wall and protruding into the room) are still partially visible. As seen above, the north and the east walls of room B2 abut respectively BF4 (forming the west boundary of rooms B1–B2) and BF16 (the south wall of the complex). A niche (width: 73 cm; depth: 38 cm) was inserted in the east wall;51 today it is only partially visible in its bottom end, due to the collapse of the roof and of the upper courses of the wall and to wind erosion. Overall, B2 is the most poorly preserved room of the building. Very scanty remains of a highly decayed floor (BF22)52 were found in association with the surrounding walls.

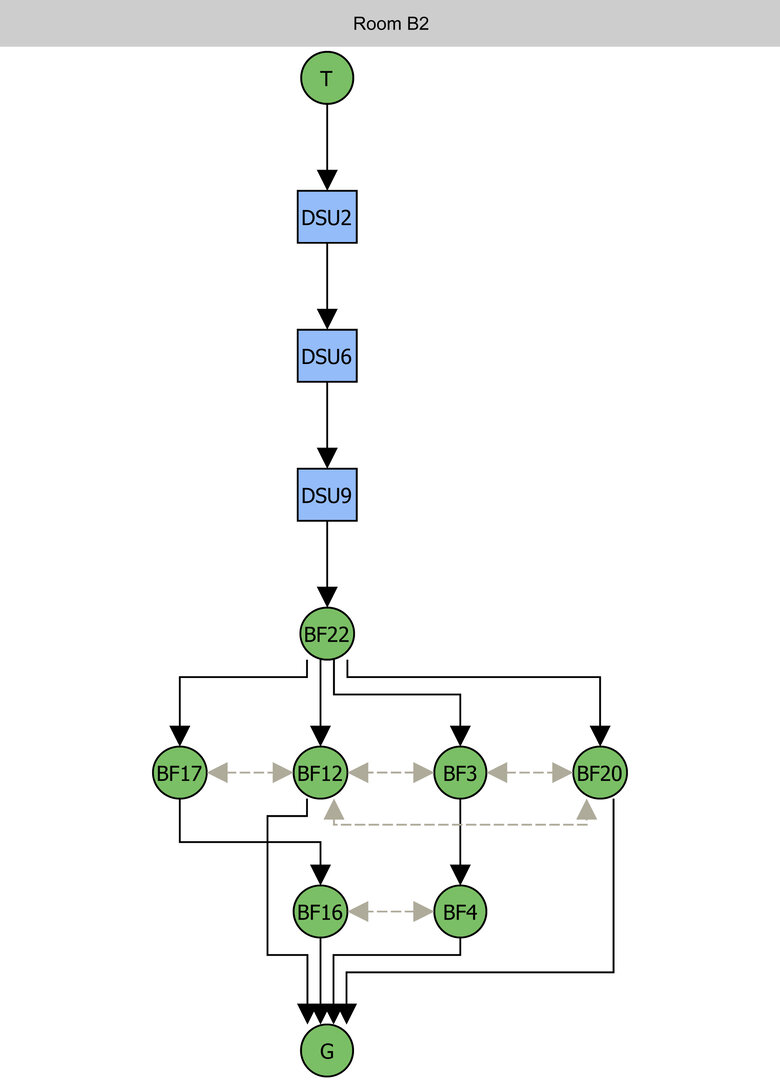

The simple stratigraphy of room B2 (Plate 2.39) consisted of a surface layer of windblown sand (DSU2),53 with a low density of inclusions, mostly pottery fragments (0.1 kg), covering a sub-surface level (DSU6)54 that was quite similar in nature to the previous one but with slightly less inclusions. The removal of this unit revealed a dark brown context (DSU9)55 at the level of a largely deteriorated clay floor (BF22). This layer, which was very rich in organic inclusions (including bones)56 and ceramic sherds (2.04 kg) and lay directly on top of gebel, was identified as occupational debris mixed with the decayed floor. The only small find that was gathered within room B2 came from this occupational layer; it is a fragmentary base of a vessel of yellow blown glass (inv. 6).

To the east of room B2, and also opening onto the rectangular court (B1), is room B3; it measures ca. 2.60 m north–south by 2.75 m east–west, and the maximum height of its preserved walls is 1.32 m (west wall BF17). The room still shows a few traces of a beaten earth floor (BF23),57 laid out on gebel.

Reflecting the symmetrical arrangement of room B2, the north wall of room B3 (BF2) abuts, at its east end, BF1, which forms the eastern boundary of the building. To the west of BF2 is a doorway (BF13; width between the jambs: 62 cm) that is the only entrance into the room from courtyard B1. Remains of the mud-brick threshold, of two jambs and a stub (BF21), bonded with the north wall and protruding into the room, are still visible.

The lower part of a niche, 44 cm wide and 37 cm deep, is set toward the north end of the east wall.58 Of particular interest, although of yet unclear function, is the white gypsum band that decorates the northeast corner of this room. This band partially frames the niche on the east wall and continues on the north wall, following an irregularly stepped pattern and ending against the stub of the doorway (Plate 2.40).59

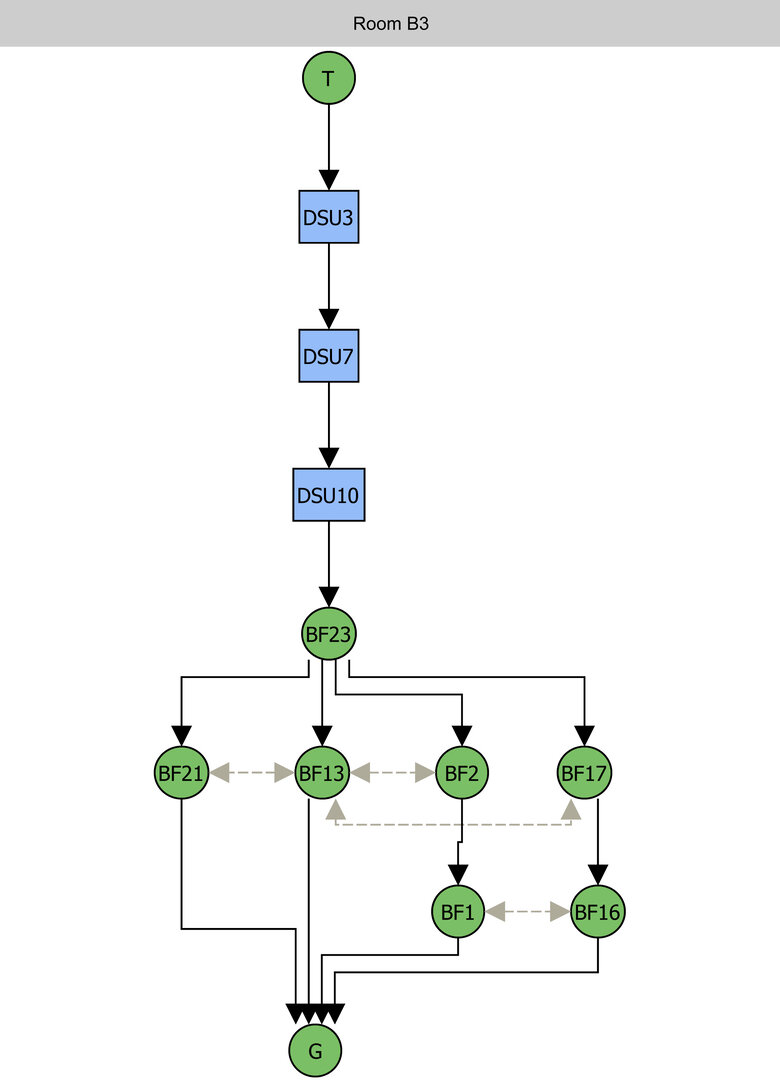

The surface layer (DSU3)60 removed from room B3 (Plate 2.41) consisted of windblown sand with a low concentration of ceramic sherds (1.15 kg), plaster, and very few fragments of mud brick. Another depositional unit of sand (DSU7)61 was found underneath, which contained more fragments of mud bricks and ceramic sherds (30 kg). Two fragments of ropes, of light yellow-brown vegetal fibers (inv. 14–15), were also found in this deposit. DSU7 extended throughout the room and covered the lowest, and most significant, archaeological context (DSU10),62 which consisted of decayed mud-brick debris (from a wall collapse) and brown sediment (from an occupational level and a deteriorated clay floor) (Plate 2.42). Several traces of palm rib impressions and straw matting were found on the mud plaster and bricks in this layer, suggesting that originally the room had a flat roof. This context, which contained a higher percentage of ceramics than the units above (10.45 kg), lay on gebel and on the scanty remains of a beaten clay floor. The few objects that were retrieved during the excavation of DSU10 consist of a fragmentary rope of light brown vegetal fibers (inv. 16) and a Greek ostrakon (inv. 7), which is an account of wheat and must written on both the convex and concave sides of the body sherd. Based on information written in the text, the ostrakon is dated to the second half of the fourth century.

The layout of rooms B1–B3 (and of the two unexcavated rooms along the north side of B1) suggests that they belonged to a residential unit, consisting of a roofed courtyard, with a hearth for food preparation, and smaller spaces opening onto it. The overall design shows a rather simplified spatial arrangement, compared with that of other houses found at Kellis or Amheida, also in the Dakhla Oasis.63 Quite peculiar is also the symmetrical layout of spaces in the building of ʿAin el Gedida and the fact that rooms B2–B3 (and the two unexcavated rooms to the north of B1) roughly share—quite unusually in a domestic context—the same dimensions. At any rate, the identification of this building as a house still stands as a reasonable possibility. The relatively small dimensions and seemingly private character of the building; the spatial arrangement of rooms opening onto a central, rectangular courtyard with a hearth placed in one corner;64 and the discovery, within the occupational level of the courtyard, of a ceramic assemblage of a clearly domestic nature, point towards the identification of this building as a residential unit. It is not clear, however, if a family inhabited this building. The symmetry of the spaces and their roughly equal dimensions (apart from the court) also suggest a structure occupied by individuals occupying same-size rooms and sharing only the central court as a communal space. The available evidence does not confirm, nor does it rule out, this hypothesis. Certainly, this would fit quite well with the possible reading of the site as an agriculturally-oriented settlement, in which people might have resided, with or without families, on a seasonal basis.65

2.3.2 Room B4

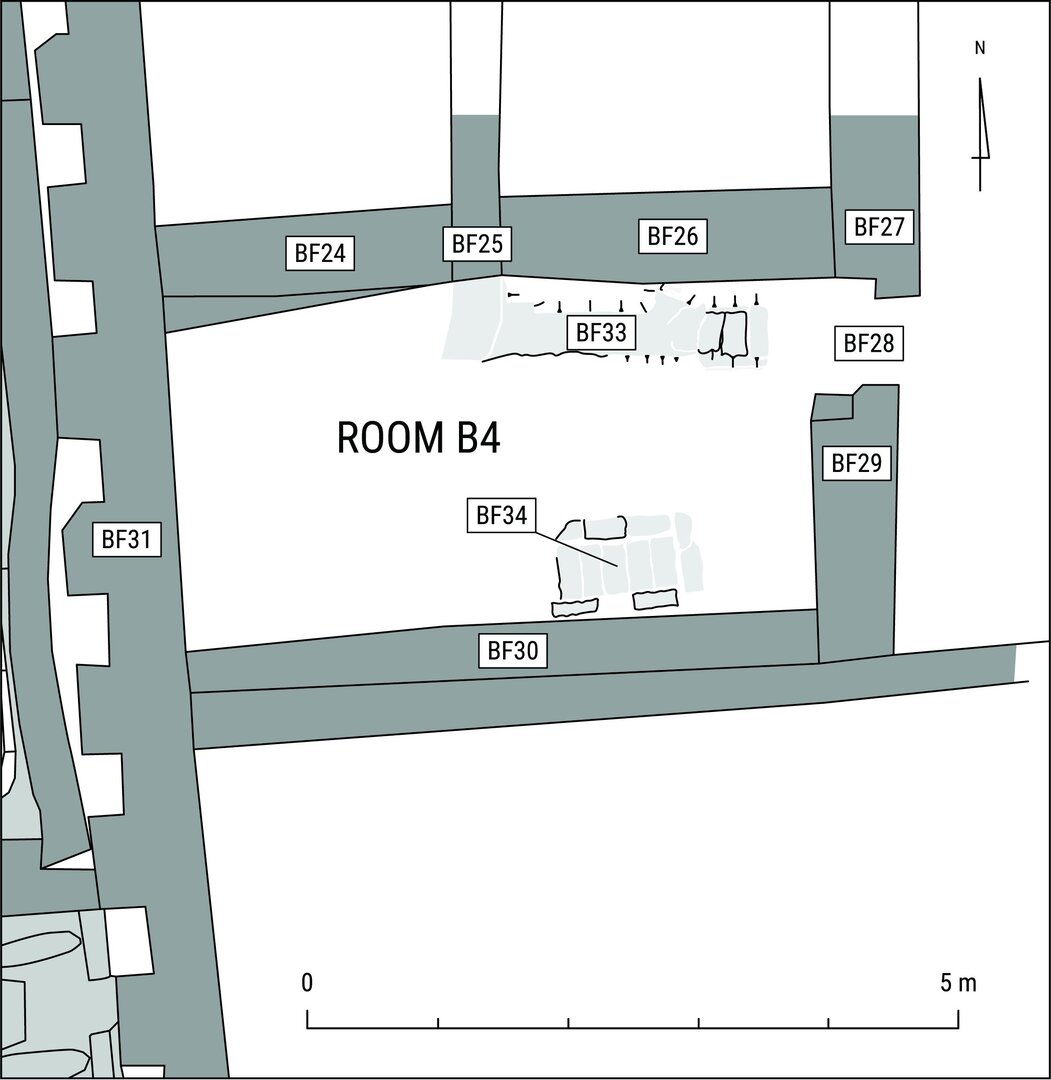

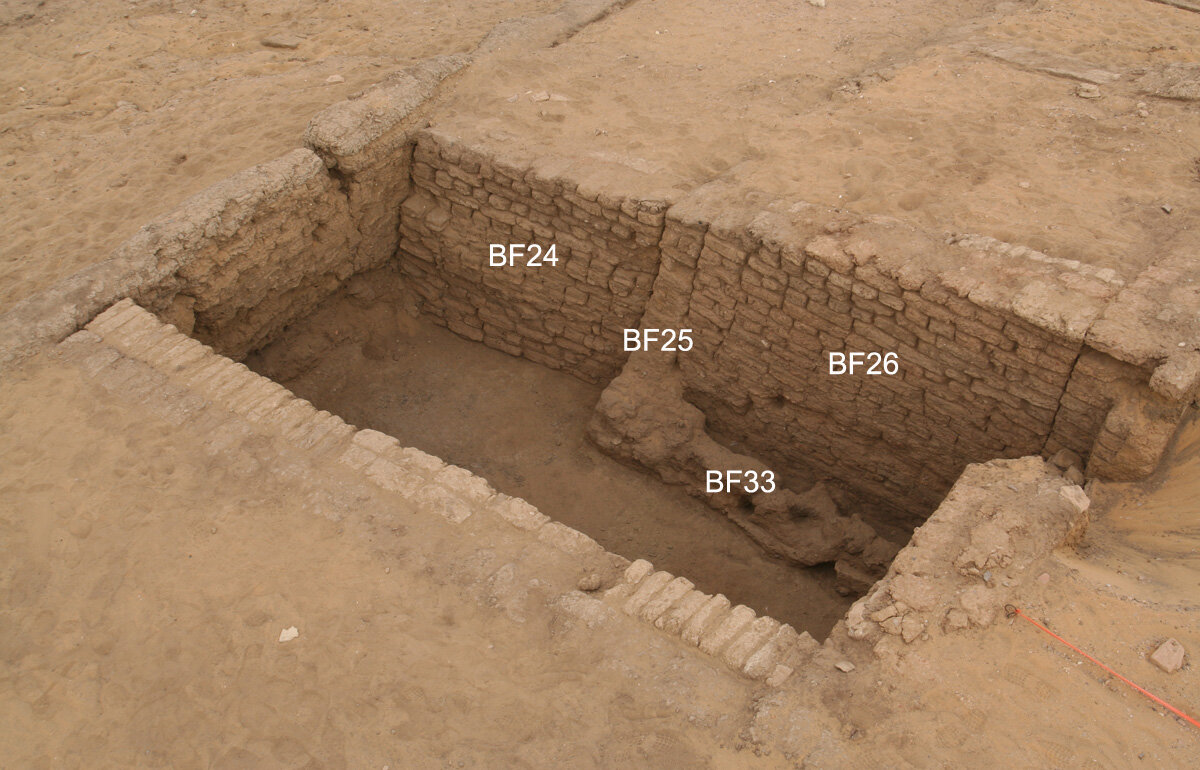

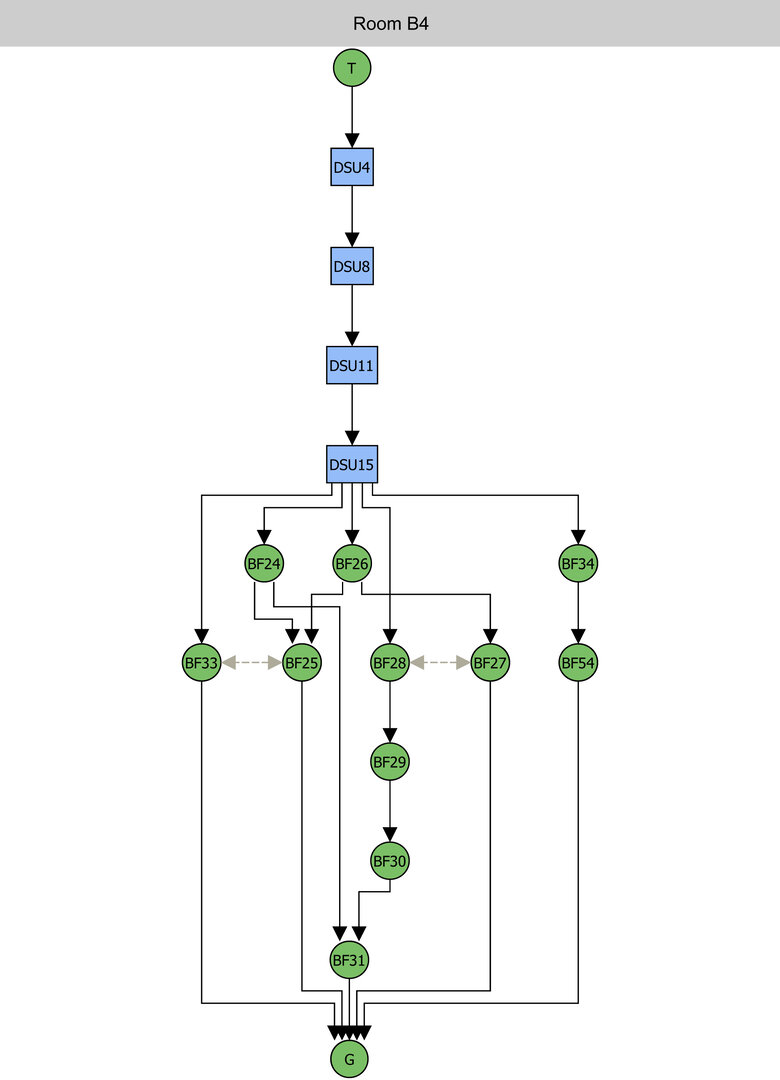

Still in 2006, a second area was selected for test trenching to the southwest of room B1–B3, where one roughly rectangular space (B4) was excavated to gebel (Plate 2.26, Plate 2.43). Room B4 is located immediately to the east of the complex of rooms B17–B24 that was investigated in 2008.66 In fact, the west wall of B4 is part of the east wall (BF31, oriented north–south) of that complex and predates the construction of room B4 (certainly in its latest stage). This space measures ca. 2.70 m north–south by 4.90 m east–west, with mud-brick walls that are preserved to a maximum height of about 2.30 m near the southeast corner.

The north side of room B4 consists of different segments, including two east–west oriented partition walls (BF24 and BF26) abutting earlier ones. In particular, BF24 abuts BF31 to the west (belonging to the western complex, as mentioned above) and BF25 to the east. BF25 is a north–south oriented wall that was partly razed down in the section that once continued into room B4. Originally, this wall was bonded with another wall (BF33) running perpendicularly to the former and that was also razed at some point, possibly when room B4 was constructed (Plate 2.44). Consistent remains of BF33 are still visible well above gebel level inside B4, suggesting that the room did not have a floor (indeed, no traces of it were identified), but was built with the specific function of serving as a dump. BF25 is abutted to the east by the second partition wall (BF26), which ends to the east abutting BF27, another north–south oriented wall (parallel to BF25). BF27 serves also as the northern sector of the east wall of room B4. The southern part (BF29) is divided from BF27 by a doorway (BF28), which was the only access into room B4 (although it is not clear if this passage was indeed in use in the room’s last phase of use).67

The remains of the doorway, consisting of two protruding side jambs and a threshold, were found in very poor condition and could not be fully excavated to gebel. BF27 abuts the south wall of the room (BF30), which is considerably narrower than the other sectors and runs along an unexcavated wall to the south. All walls are built in a very poor construction technique in English bond, which is particularly irregular in the case of south wall BF30; indeed, four of the visible courses of bricks are headers placed on edge.

During the excavation of the midden (B4), remains of another wall (BF34, Pl. 2.45) were uncovered at foundation level along the south wall, clearly predating the latest phase of use of the room. BF34, as well as the above-mentioned evidence of earlier walls, testify to the substantial alterations to which pre-existing architectural features underwent in the area subsequently occupied by room B4, with the razing of older walls and the addition of new ones. Unarguably, the investigation of the rooms and buildings to the north, east, and south of the dump would allow us to shed light on the occupational history not only of room B4, but of the entire area.

The highest depositional level (DSU4),68 removed from the entire area of room B4 (Plate 2.46), consisted of windblown sand and fragments of mud bricks and ceramics (4.40 kg). Among the small finds that were retrieved in the surface layer are fragments of undecorated textile (inv. 3, 11, 12) and a Coptic ostrakon (inv. 4) of nine lines; the latter is a letter that mentions individuals belonging to a monastic community. Based on palaeography, the ostrakon was dated to the fourth century (possibly the second half). Below DSU4 was another layer of sand (DSU8),69 still covering the whole room and sharing similar characteristics with the previous unit, except for a higher density of mud-brick fragments (likely from the collapse or dismantling of the surrounding walls) and pottery inclusions (204.5 kg). Four fragments of textile (inv. 21) and a headless Bes amulet of blue faience with yellow glaze (inv. 5)70 were collected during the excavation of DSU8. The removal of this depositional unit revealed a layer (DSU11)71 of sand of a darker color, likely due to its mixture with mud-brick dust. It contained a few pebbles, charcoal, bones, ceramic sherds (22.26 kg), and a fragment of a rope made of light brown vegetal fibers (inv. 13). Underneath, and filling the entire room down to gebel, was a thick, dark gray/ brown layer of ash mixed with mud-brick dust (DSU15; Pl. 2.47).72 This unit, which was thicker along the perimeter of the room than in the center,73 contained fragments of glass and glass slag, a high percentage of charcoal, pottery sherds (219.08 kg), and organic inclusions, such as wood, fruit seeds, and bones. The small finds that were uncovered in DSU15 consist of two bracelet fragments made of black dull glass (inv. 23, 24), two complete cylindrical beads (inv. 19, of gold leaf between two layers of transparent glass, and inv. 20, of blue dull glass), an incomplete sandal sole of vegetal fibers (inv. 22), an elongated conical shell (inv. 101) with a perforation at the broad end (likely used as a pendant), and an enigmatic piece of coroplastic (an incomplete head molded around a pit, inv. 27). The excavation of DSU15 brought to light also a complete Greek ostrakon of nine lines (a receipt for annona of horse archers) that is dated to the fourth century (inv. 9). A coin (inv. 548) was found while cleaning the features of room B4. Due to its very poor condition, no dating could be established.

There is a high probability that room B4 was not the primary context for several of the objects found during its investigation (especially within DSU11 and DSU15), as they were likely thrown into the room together with the ash refuse. Indeed, the presence of a thick layer of ash, charcoal (with no traces of burning along the walls), and fragmentary material—organic and not—filling the entire room up to sub-surface points to the use of room B4, at least in its latest phase, as a domestic midden.

2.4 Notes

As previously noted by the Egyptian excavators: see Bayoumi 1998: 58. On mud-brick architecture in Dakhla, see Schijns 2003.↩︎

See the discussion of the two rooms below. Evidence of earlier walls razed down or partially reused was found also in area B, for example in the church (room B5) and the large gathering hall to the north of it (room A46). See the analysis carried out in Chapter 3.↩︎

Seemingly built at a later time than the original, central core of structures in area A.↩︎

See Section 2.1.1 below.↩︎

Upper elevation: 111.581 m.↩︎

Remains of vault springs are visible particularly along the west side (AF7), in addition to very few traces (AF3) above the east wall.↩︎

Vault springs AF12 and AF16 respectively.↩︎

As mentioned above, the same wall extends eastwards, forming the north boundary of rooms A3–A4. It is possible that the three niches were built taking advantage of preexisting wall AF1; another possibility is that in fact AF1 postdates the construction of AF15, in which case the three openings had been originally conceived as windows and not niches. However, no comparative evidence was found for windows set at such a low height from ground level anywhere at the site, which makes this identification less likely.↩︎

Upper elevation: 111.879 m.↩︎

AF56 above the east wall (northern end) and AF59 above the west wall.↩︎

Nicholas Warner, who visited the site, confirmed this possibility (personal communication to Gillian Pyke, February 2006).↩︎

Upper elevation: 112.016 m.↩︎

In room A14: AF31 above north wall AF30 and AF34 above south wall AF33. In room A15: AF24 above north wall AF33 and AF27 above south wall AF26.↩︎

Upper elevation: 112.259 m.↩︎

Upper elevation: 112.224 m.↩︎

The plaster fragment (maximum width: ca. 12 cm; maximum height: ca. 8 cm) is located 1.19 m above floor level and 1.4 m from the south end of room 14’s east wall.↩︎

The clearance of the sand revealed that part of the room, against the SE corner, had been left unexcavated in the 1990s. The full investigation of the room, begun in 2006, was completed, due to time constraints, only during the 2007 season.↩︎

AF42 above the east wall and AF48 above the west wall.↩︎

Upper elevation: 111.669 m.↩︎

Upper elevation: 111.730 m; lower elevation: 111:360 m; max. thickness: 37 cm.↩︎

For a detailed analysis of the three ostraka, see Chapter 10 in this volume.↩︎

The clearing of sand from this space was not completed because of the extremely precarious condition of some of its features; unfortunately, several other structures throughout the site share similar conditions.↩︎

The doorway opening onto corridor A8 was not excavated; therefore the existence of a threshold or other features could not be ascertained.↩︎

As there is no documentation of the investigation of the room in the 1990s, it is difficult to determine whether such disturbances occurred exclusively in antiquity or also in modern times.↩︎

As proved by the fact that the wall forming the east face of the staircase is bonded with the south wall of room A7.↩︎

Photographic evidence exists of its original location in situ.↩︎

Yeivin 1934: 114–15, and Depraetere 2002: 123–25.↩︎

Several traces of ash and burning marks were detected in the proximity of this feature, especially against the east wall of room A6. This fact led Mr. Bayoumi to identify the feature as part of a rectangular oven, also on the basis of a comparison with modern examples still in use in the oasis (personal communication, January 2006). The available evidence is not conclusive on this identification.↩︎

As preliminarily proposed by R. Bagnall, C. Hope, and A. Mills (personal communications).↩︎

Churcher and Mills 1999: 251–65. A published farmhouse from Dakhla is in Mills 1993.↩︎

Hope 2007a: 16–22. A plan of the columbarium is published in Hope and Whitehouse 2006: 315.↩︎

Several pigeon towers were also found at the site of Karanis, in the Fayyum, resembling the typology of the columbarium from Kellis: see Davoli 1998: 85.↩︎

On the preliminary test trenching carried out in rooms B1–B3 and B4, see Section 2.3.↩︎

For a discussion of the archaeological evidence of the complex, see Chapter 6 in this volume.↩︎

Apart from room A46, first excavated by the Egyptian team in the mid-1990s.↩︎

Apart from a rectangular room, with plastered walls and a rounded niche, that was found partially empty in the middle of the mound.↩︎

Bayoumi (personal communication, February 2005).↩︎

Peter Sheldrick briefly visited the area in 2012 and noticed fragments of what may be human bones (personal communication, January 2012).↩︎

BF10 (the doorway to the west of BF7) has a width between the jambs of 67 cm, while BF9, to the east of the same wall, has a width of 68 cm.↩︎

Ca. 90 cm above ground level.↩︎

Their width is given below in the discussion of rooms B2–B3.↩︎

Upper elevation: 113.646 m.↩︎

Only patches of a floor were found in room B3 and almost none in room B2.↩︎

Matching the stratigraphy of both rooms B2 and B3.↩︎

Upper elevation: 114.904 m; lower elevation: 114.439 m; max. thickness: 47 cm.↩︎

Upper elevation: 114.439 m; lower elevation: 113.524 m; max. thickness: 91 cm.↩︎

Upper elevation: 113.894 m; lower elevation: 113.436 m; max. thickness: 46 cm.↩︎

See Section 8.3.1 in this volume.↩︎

Upper elevation: 114.849 m; lower elevation: 114.634 m; max. thickness: 22 cm.↩︎

Upper elevation: 113.491 m; lower elevation: 113.271 m; max. thickness: 22 cm.↩︎

Ca. 90 cm above ground level.↩︎

Upper elevation: 113.551 m.↩︎

Upper elevation: 114.744 m; lower elevation: 114.154 m; max. thickness: 59 cm.↩︎

Upper elevation: 114.154 m; lower elevation: 113.634 m; max. thickness: 52 cm.↩︎

Upper elevation: 113.759 m; lower elevation: 113.479 m; max. thickness: 28 cm.↩︎

On bone remains found at the site, see Chapter 12 of this volume.↩︎

Upper elevation: 113.601 m.↩︎

91 cm above bedrock.↩︎

P. Davoli pointed out that similar bands were also found at the site of Amheida (personal communication, 2006).↩︎

Upper elevation: 114.624 m; lower elevation: 114.309 m; max. thickness: 32 cm.↩︎

Upper elevation: 114.309 m; lower elevation: 113.514 m; max. thickness: 80 cm.↩︎

Upper elevation: 113.654 m; lower elevation: 113.394 m; max. thickness: 26 cm.↩︎

On a recently published house at Amheida, see Boozer 2015: pt. III. Evidence of first–fourth c. Roman houses was found at several sites throughout Egypt, including Kellis in the Dakhla Oasis (Hope 1991; Hope 2003; Hope 2007b; Hope and Whitehouse 2006; Hope et al. 1989; Hope et al. 2006); Douch/Kysis in Kharga Oasis (Reddé 2004); Karanis (Boak and Peterson 1931; Boak 1933; Husselman 1979); Soknopaiou Nesos (Davoli 1998: 39–71); Hawara (Uytterhoeven 2010); Tebtynis (Davoli 1998: 179–210; Hadji-Minaglou 2007; Hadji-Minaglou 1995); Oxyrhynchus (Bowman et al. 2007); Elephantine (Arnold, Haeny, and Schaten 2003); Alexandria (Rodziewicz 1984; Rodziewicz 1976); Marina el-Alamein (Medeksza and Czerner 2003).↩︎

Two structures reflecting a partially similar layout, with two smaller rooms of roughly equal dimensions opening onto a larger rectangular space, were excavated by the SCA in the mid-1990s along the southeast end of mound I, although their identification as domestic residential units is not proved beyond doubt.↩︎

BF27 and BF29 may in fact be considered sectors of the same wall; however, they were preliminarily assigned different numbers, as further excavations are needed in order to discern the full length of these walls and the relationships with their neighboring features.↩︎

Upper elevation: 114.879 m; lower elevation: 113.874 m; max. thickness: 100 cm.↩︎

Upper elevation: 113.984 m; lower elevation: 113.184 m; max. thickness: 80 cm.↩︎

See Section 11.3.2 (cat. no. 26) in this volume.↩︎

Upper elevation: 113.214 m; lower elevation: 112.929 m; max. thickness: 29 cm.↩︎

Upper elevation: 113.199 m; lower elevation: 112.414 m; max. thickness: 79 cm.↩︎

Possibly due to the pattern of refuse-dumping, which occurred from outside the room and along its walls.↩︎