1 Introduction

This is an online digital edition from ISAW Digital Monographs. The print edition of this work can be consulted at https://isaw.nyu.edu/publications/isaw-monographs/ain-el-gedida

1.1 ʿAin el-Gedida and the Dakhla Oasis

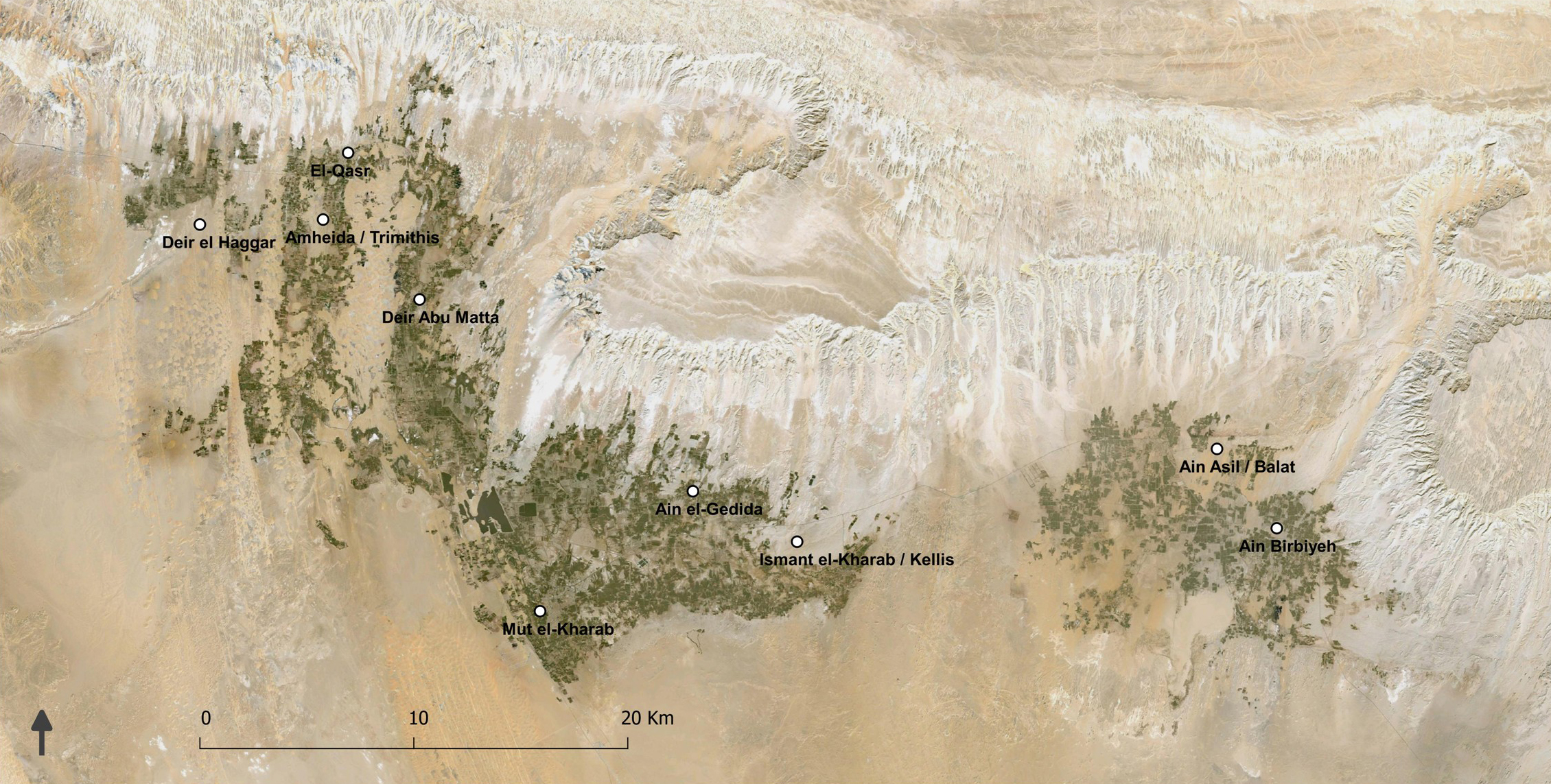

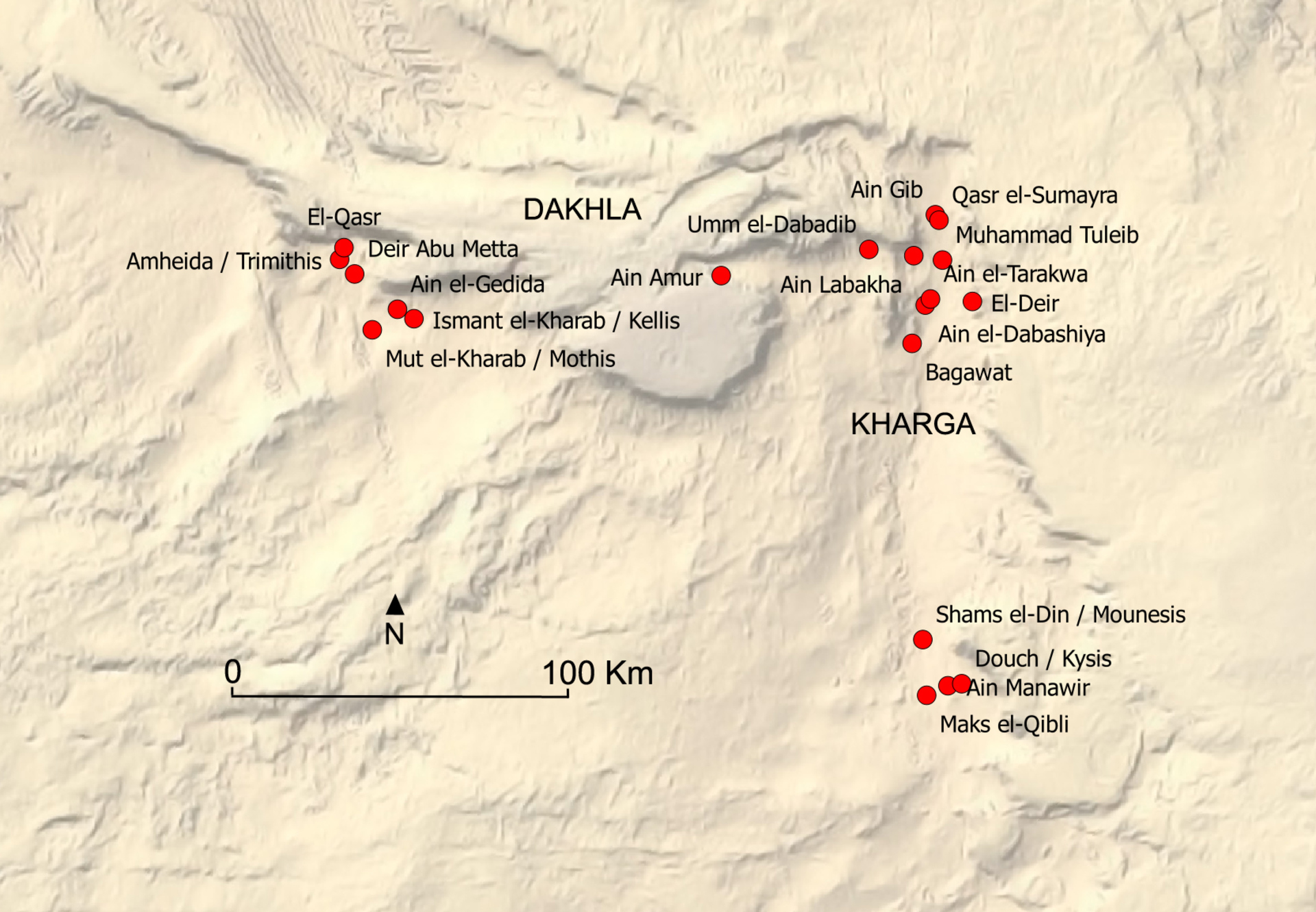

The Dakhla Oasis lies in the Western Desert of Upper Egypt, ca. 800 km southwest of Cairo, 280 km southwest of Asyut, and about 300 km west of Luxor (Plate 1.1, Plate 1.2) It is one of the five major oases that lie west of the Nile Valley, including Siwa, Bahariya, Farafra, Dakhla, and Kharga.

Dakhla is oriented northwest–southeast and has an extension of ca. 80 km from east to west and ca. 30 km from north to south, covering a green area of ca. 410 km². It lies to the south of an escarpment, 300 to 400 m high, which separates the depression of the oasis from the northern Libyan plateau.1 In fact, the oasis does not consist of a continuum of fertile, irrigated land, but rather of a set of smaller oases, divided by the desert. To the west of Dakhla are the dunes of the Great Sand Sea, and to the south is a vast desert expanse leading to Sudan. About 190 km east of Dakhla, and separated from it by desert land, is the Kharga Oasis. Apart from the escarpment, the only mountain of the depression is Gebel Edmondstone, located toward the northwest end of the oasis. Smaller outcrops and spring mounds dot the relatively flat landscape, which is at a height of 92–140 m above sea level.2

The natural environment of Dakhla is harsh. The average temperatures are high, soaring to 40° and beyond during the summer months.3 Also, significant temperature differences exist between day and night, especially in the winter. Precipitation is a very rare occurrence, while northern winds hit the oasis with fierce intensity, causing sandstorms that halt any human activity.4

The oasis lies in a region that is the result of geological phenomena occurring since the Early Cretaceous.5 Surveys carried out in Dakhla gathered evidence, datable from the Late Cretaceous to the Quaternary Eras, proving that large parts of the oasis were covered with water.6 Afterwards, dramatic environmental changes led to a progressive desertification process of the entire region, which obliterated the rich prehistoric fauna and flora and the first human settlements of the oasis, while wind erosion progressively cancelled their traces.

In antiquity, several roads and caravan routes connected Dakhla with the neighboring oases, the Nile Valley, and farther regions, mostly through the northern escarpment or via Kharga (Plate 1.3).7 The northern escarpment is dotted with passes, which allow access from the oasis onto the plateau and further north.8 The Darb el-Tawil is a desert track linking Dakhla to Manfalut, near Asyut in the Nile Valley, and was one of the two main routes used in antiquity to the oasis. Another route, only partially known, heading to Asyut is the Darb el-Khashabi; it sets off at the village of Ismant and heads straight north onto the escarpment via the Naqb Ismant. The main alternative route to the Nile Valley is via Kharga, which is connected to Dakhla through the Darb ʿAin Amour, a road crossing the Abu Tartur Plateau. A longer, but easier, path from Dakhla to Kharga is the Darb el-Ghubari, which runs further south and bypasses the Abu Tartar Plateau. The Darb el-Farafra leaves from El-Qasr in the western part of the oasis and after crossing the escarpment at Bab el-Qasmund runs northwest to the Farafra Oasis, continuing thereafter to Bahariya and further north. The Darb Abu Minqar is the modern roadway, leaving from El-Qasr and passing by the Gebel Edmondstone in a northwest direction (toward Farafra and beyond). The only route heading south of Dakhla is the Darb al-Tarfawi, crossing the inhospitable southwestern desert.

Life in Dakhla has been made possible since antiquity by easy access to water, located in aquifers under the sandstone bed of the oasis.9 The low elevation of the depression makes it relatively easy to reach subterranean water, which is rich in sulfur and iron. Hundreds of wells are spread throughout the oasis, many of which date to the Roman period, and several springs can also be found.10 An extensive network of irrigation canals brings the water from the wells, which nowadays are often operated with mechanical pumps, to the cultivated fields.11 A few traces of what may have been ancient qanats12 (irrigation systems based on a series of vertical shafts connected through a sloping underground channel and transporting water from its source to destination), have been detected, although not yet excavated, in the oasis.13 This paucity of archaeological evidence seems to contrast with the abundance of remains found in the neighboring Kharga Oasis, raising questions about the possible reasons.14

Evidence of human activity in Dakhla can be traced back to ca. 400,000 BCE, in the Lower Palaeolithic.15 The Neolithic is also represented, with remains that are datable to the first half of the ninth millennium BCE.16 The oasis lies far from the Nile Valley but, notwithstanding its location that favored a relatively high degree of isolation, it held regular contacts with the people of the Valley throughout its history. In the Pharaonic period, Dakhla (together with its neighboring oases) was a strategic outpost on the way to Nubia and an economically significant site.17 According to A. J. Mills, the oasis experienced the arrival of a substantial number of migrants/settlers from the Valley starting around 2300 BCE, likely employed in the agricultural exploitation of the fertile land.18 Archaeological evidence of settlements from the Old to the New Kingdom and into the Persian Period was found, although the number of Old Kingdom sites vastly outnumbers those from the Middle and New Kingdom.19 The oasis was continuously inhabited under the Ptolemies (although the evidence for this period is only now becoming substantial as a result of excavations at Mut)20 and, after 30 BCE, under the Romans, when intensive agricultural development took place.21 At an administrative level, Dakhla became part of the “Great Oasis”, which included Kharga, and was then divided into the Mothite and Trimithite nomes in later Roman times.22 It was under the administration of Rome that the oasis reached its highest population density until modern times and its economy thrived.23 Water and fertile land were not the only reasons that attracted the interest of the Romans in the Great Oasis. Indeed, the region was strategically located at the periphery of the empire and along major caravan routes. These factors were likely the rationale for the establishment, throughout the region and especially in Kharga, of military outposts and fortresses, with the aim to protect the roads and the empire’s commercial interests.24

Dakhla was populated also in the Byzantine period, although with evidence for economic decline and the abandonment, between the end of the fourth and the fifth century, of some areas of the oasis,25 and from the Arab conquest until modern times.

Its “re-discovery” began in the early nineteenth century, with the exploration of several European travelers who wrote about the oasis, its people, and its significant archaeological remains.26 The first European traveler to leave a written record of his trip to Dakhla was Sir Archibald Edmondstone, in whose honor the gebel at the west end of Dakhla was later named.27 His arrival in the oasis in 1819 was immediately followed by that of Bernardino Drovetti, a French diplomat of Italian origin, and then by several other Europeans, including Frédéric Cailliaud (1819), Frederic Muller (1824), and John G. Wilkinson (1824). In 1874, Dakhla was reached by the scientific expedition organized by the German Gerhard Rohlfs, who carefully recorded the topography of the oasis.28 In 1894, Captain H. G. Lyons went to Dakhla, followed in 1898 by Hugh Beadnell, who surveyed the oasis for the Geological Survey of Egypt, which had been founded in 1896.29 In 1908, H. E. Winlock and Arthur M. Jones traveled to Dakhla, and Winlock published a detailed account of his trip in 1936.30 Still today, his diary is a source of significant information on the oasis before the modernization process of the mid-twentieth century. W. J. Harding King followed in 1909, on a mission for the Royal Geographical Society.31

The relative geographical isolation experienced by Dakhla, the natural environment, and the dry climate have favored, in contrast to what often happens in the Nile Valley, the excellent preservation of archaeological sites and artifacts. Nonetheless, it was only from the middle of the twentieth century, with the work of Ahmed Fakhry, that the oasis attracted significant scholarly attention.32 In 1977, the Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale (IFAO) began its scientific activity in Dakhla. In 1978, an international, multidisciplinary research venture—the Dakhleh Oasis Project (D.O.P.) —was created, with the aim to investigate all aspects of the oasis environment, its changes, and their effect on the development of human presence and activity in the oasis.33 Research under the D.O.P. umbrella spans the period from Prehistory to the modern era; it is independently carried out by different teams and institutions, but always in a collaborative fashion, which promotes the exchange of knowledge and data among the various disciplines.34

1.2 Early Christianity in Dakhla35

Because ʿAin el-Gedida will appear in what follows to have been part of a fourth-century Christian environment,36 some preliminary remarks on the evidence for early Christianity in the oasis may be helpful. It is during the fourth century that Christianity seems to have spread and developed dramatically in the region of the Western Desert, the evidence for earlier centuries being negligible.37 The particularly rich heritage of Early Christian monuments from the Kharga oasis, to the east of Dakhla, points to the flourishing of Christian communities in the region long before the Arab conquest.38 Churches, monasteries, and cemeteries excavated or surveyed at Kharga are witnesses of the profound influence Christian art and architecture had on the natural and urban environment of that oasis.39

Although the archaeological evidence for Christian monuments is more abundant, and is relatively better known, with regard to Kharga, the Dakhla Oasis also proved to be a suitable location for thriving Christian communities already at an early stage. In 1908, H. Winlock commented on the scarcity of Christian antiquities throughout the oasis, especially in comparison (as mentioned above) with the abundant and visible evidence from the nearby Kharga Oasis. As a possible cause, he blamed the relative distance of Dakhla from the Nile Valley and its Roman garrisons, which exposed the oasis to the dangers of invasion and destruction by neighboring nomadic tribes, which might have caused the abandonment of most settlements during the late Roman period.40

The Dakhleh Oasis Project survey, carried out from 1977 to 1987, recorded well over one hundred archaeological sites with phases of occupation assigned (on the basis of ceramic evidence) to the Byzantine Period (ca. 300–700 CE).41 For most of the sites listed as “Byzantine”,42 however, no remains were found pointing to their use by a specifically “Christian” community. The information that was collected allowed a preliminary dating of these sites, including large settlements but also smaller loci such as caves and cemeteries, to Late Antiquity.43 Substantial data gathered during the excavation of cemeteries at Kellis and, quite recently, at Deir Abu Matta and near Muzawwaka, provide evidence on Christian burial customs in Dakhla, which are consistent with those found at other Christian sites in Egypt: bodies lying supine with their head to the west and almost no goods associated with them.44 Yet, for most sites listed by the D.O.P., no precise conclusions can be drawn on the religious affiliation of the people living at those settlements. Literary, documentary, and archaeological evidence has shown that Egypt became a profoundly Christianized country already in the fourth century.45 This might lead one to assume that Christian communities (including Manichaeans, whose existence is attested to in the oasis46) were somehow linked to most or all of the “Byzantine” sites identified in Dakhla, and indeed that is very likely by the later fourth century; however, any generalization is prevented by the fact that people from different ethnic, cultural, and religious backgrounds co-existed in Egypt in Late Antiquity. At least some Egyptian temples were still operating in the third century and perhaps even the first quarter of the fourth.47 Only an in-depth archaeological investigation could shed light on such matters in relation to those sites.

1.2.1 Kellis/Ismant el-Kharab

Significant evidence of a Christian presence in Dakhla during Late Antiquity comes from the site of Kellis/Ismant el-Kharab, thanks largely to the work of Colin Hope and Gillian Bowen.48 The D.O.P. survey of 1981–82 found evidence of three churches, one located along the west edge of the village, and two, part of an extensive, multi-roomed complex, at the south end of the settlement.49 The western church, excavated in 1992–93, is oriented to the east (Plate 1.4). It measures ca. 15 m east–west by 7 m north–south and consists of two rooms, one to the west, possibly used as a narthex, and one to the east, with a passageway centrally placed within the shared wall. An apse with a raised floor, accessed via a step, is located along the east wall. The conch is flanked by engaged semi-columns and in front of it is a raised platform, accessible from the west through a couple of steps. Two doorways, placed to the north and south of the apse, open onto small side-rooms. Mastabas (low benches) run along the walls of the two rooms of the church, the only access to which is through a doorway located in the south wall of the narthex.50 This opens onto a cluster of seven rooms forming an architectural complex together with the church. The area covered by these spaces, whose function is unclear, roughly equals the church in size.51 The only entrance to the complex is located in the southwest corner; it opens onto a large rectangular room with mastabas, possibly functioning as an anteroom. Two Christian burials were found against the east wall of the church and others in its proximity. These discoveries led the excavators to identify the complex as funerary.52 According to the numismatic evidence, the foundation of the complex occurred around the mid-fourth century CE.53 The ostraka found in the building are largely dated to the third quarter of the fourth century, with links that can be established with similar material from the nearby site of ʿAin es-Sabil.54

The two churches built in the southeast periphery of Kellis once belonged to a rather large complex (Plate 1.5).55 The so-called Small East Church is located near the southeast corner of its enclosure, built against the east wall. It was partially investigated in 1981–82 by J. E. Knudstad and R. A. Frey and fully excavated in 2000 by Gillian Bowen.56 The church, the overall dimensions of which are ca. 10.5 m north–south and 9.5 m east–west, consists of two rectangular, interconnected rooms oriented east–west. To the north is a large hall, once barrel-vaulted, that was originally accessible through a doorway placed in the middle of the north wall (bricked in at some point in antiquity), and another door in the south half of the west wall. From this room one accessed the church to the south via two doors, one (larger) located in the middle of the walls separating the two rooms and one (narrower—and the result of later modifications) at the west end of the same wall.57 Bowen found ample evidence that the room had not been built originally as a church, and its conversion into an ecclesiastical building entailed several alterations. The most significant was the addition of a raised, tripartite sanctuary set against (and partially into) the east wall, with a central apse, delimited by two pilasters and richly decorated, and two side rooms. According to ceramic and numismatic evidence, the Small East Church, which shares several and significant similarities with the church of ʿAin el-Gedida, was in use during the first half of the fourth century.58

Bowen argues that the Small East Church is to be considered a domus ecclesiae, a “community house” used by a group of Christians as a place for worship and altered to suit their specific needs.59 Therefore, it would slightly predate the construction of the Large East Church, which was, instead, the result of careful planning and possibly served a fast-growing Christian population at Kellis.60 The church, built against the southeast enclosure wall of the complex, is a rectangular building oriented east–west and measures ca. 17 m north–south by 20 m east–west.61 The remains of the building are in fairly good condition, with some of the walls standing to a considerable height. Access was originally through three doorways located along the western wall and connecting the church with the larger ecclesiastical complex. The material used for the construction is mud brick, and most of the features were once covered with mud plaster and then whitewashed. The main body of the church is divided into a central nave and two side aisles by two rows of six columns. The bases of the two columns at the west end of both colonnades show that they originally had a trefoil shape. A west return aisle (a common feature of Upper Egyptian Christian architecture) was created by adding an additional column between the north and south colonnades, against which is a mud-brick stepped platform.62 To the east, a transverse aisle with four columns completes the ambulatory, which runs along the four walls of the church and surrounds a central area paved with flagstones. Mastabas are built against the north, west, and south walls. The north and south intercolumniations were originally sealed with wooden screens, as well as the northwest intercolumniation of the return aisle.63 A raised apse is centrally placed against the east wall and framed by two engaged pilasters; the floor of the sanctuary consists of triangular mud bricks. A rectangular bema, accessed by two steps at its north and south ends, is located in front of the apse and protrudes into the transverse aisle.64 The apse is flanked by two small pastophoria, accessible from the transverse aisle; the south room is also directly connected with the apse via two steps.

A set of four rooms is located to the south of the church, accessed through the south aisle. The function of three of these spaces is unknown; a staircase and two ovens were found in the westernmost room, which likely served as a kitchen for the baking of bread used in the liturgy.65

The archaeological investigation revealed the existence of substructures predating the construction of the church, which, on the basis of numismatic analysis of the coins found in it, occurred under the reign of Constantine I.66 Therefore, the archaeological evidence points to a dating, for the foundation of the Large East Church and of the other churches of Kellis, within a relatively short time range, i.e., the first half of the fourth century. This was undoubtedly a period of intense growth for Christianity in the oasis, as confirmed by the discovery of the ecclesiastical complex of ʿAin el-Gedida, which shares the same early chronology.67

1.2.2 Deir el-Molouk

In addition to Kellis’ rich archaeological evidence, other sites in Dakhla testify to the existence of Christian communities in the oasis throughout Late Antiquity.68 The 1977–1987 D.O.P. survey listed two churches whose substantial remains are still visible above ground level. One is found at the site of Deir el-Molouk,69 located a few kilometers northwest of Masara, and consists of a cruciform building made of mud bricks (Plate 1.6).70 It had a domed roof at its center and an entrance located, according to the D.O.P. surveyors, along the poorly preserved north wall.71 It was internally divided into nine square spaces by four cruciform pillars centrally placed. Three apses with small niches were built against the east wall and three additional conches were located at the center of the north, west, and south walls, visually emphasizing the cruciform shape of the building. To the south of the church, and built against it, was a square room ending with a semicircular apse along its east side. This space was not interconnected with the main building and was accessible through a narrow room built outside the south apse of the church. The south room, which carried traces of painted plaster, was possibly built shortly after the construction of the church and functioned as part of the same complex. Subsequent architectural alterations affected the structure, as proved by the addition of later walls near the southwest corner of the church and the entrance to the south room. The dimensions of the complex, including the church and the south room, are ca. 17.5 m north–south by 15.5 m east–west. Its chronology is unclear, lacking almost any relevant dating material. However, the little evidence gathered from the test trenching points to a considerably later period for its construction than for the other churches currently known in the oasis.

1.2.3 Deir Abu Matta

The archaeological remains of Deir Abu Matta,72 located ca. eight km southeast of the town of El-Qasr and ca. six km southeast of the archaeological site of Amheida (ancient Trimithis), had already been noticed in 1908 by H. E. Winlock.73 The area of the visible archaeological remains is fairly limited and is surrounded to the north, west, and east by some desertic land, habitations, and cultivated fields, and to the southeast by a paved road. In 1980, D.O.P. members surveyed the mound atop which a church is located and carried out test trenching inside the basilica.74 An archaeological project involving the investigation and documentation of the church and adjacent structures began at the end of 2007, under the direction of Gillian Bowen. Full excavation started in 2008 and continued in the following years.75

The remains of the church are the most impressive architectural features on site (Plate 1.7). The building is oriented east–west and is rectangular in shape, measuring ca. 24 m east–west by 10.35 m north–south. The mud-brick walls, which were built in sections, are over 1 m thick and are still standing several meters above ground level. They once supported a beamed roof, as suggested by holes piercing the south wall. A triconch is set inside the church along its east wall, with an entrance framed by two engaged pillars. To the sides of the lateral conches, against the northeast and southeast corners of the building, are L-shaped pastophoria. According to Peter Grossmann, the church was originally divided into a nave and two side aisles by two rows of six square pillars, with an additional L-shaped pillar at the west end.76 A return aisle along the west side of the building joined the two colonnades by means of two square pillars, forming an ambulatory around the central nave. A mastaba is still visible against the northern section of the west wall. Another bench—no longer preserved—was once located against the south wall. Evidence of a relatively narrow door—possibly a secondary entrance into the church—was detected toward the west end of the north wall.77

Test trenches were dug along the north wall of the church between 1979 and 1980 and since 2008. These revealed numerous Early Christian burials, although some of them, at least those excavated more recently, were found to have been disturbed.

Bowen documented considerable evidence of different construction phases in the area of the church.78 Architectural features predating the construction of the basilica are visible to the north of the church and underneath it to the east. A wide, tower-like building was also excavated to the west of the basilica, in addition to the remains of other architectural features. Some of these structures seem to predate the basilica, while others were built possibly in phase with it; evidence of later alterations was also detected. It is possible that at least some of the structures excavated in the proximity of the church were associated with a small-scale monastic establishment,79 whose existence in Late Antiquity is suggested by the modern name of the site.80 However, Bowen has recently argued that no conclusive evidence is available to corroborate the identification of the excavated complex as part of a monastery.81

According to the D.O.P. report, fifth-century coins and ceramics datable from the fifth to the seventh century were collected during the survey and the test excavation.82 The finds collected during the 2008–2011 seasons, which include mostly ceramics, coins, and a few ostraka, were all dated to the fourth–sixth century CE, with very little evidence from earlier or later centuries.83 According to Bowen, the construction of the basilica took place during the fifth century, thus earlier than previously thought.84

1.2.4 ʿAin es-Sabil

The well-preserved remains of another church came to light in Dakhla in 2009. Kamel Bayoumi, of Dakhla’s Islamic and Coptic Inspectorate, found the complex at the site of ʿAin es-Sabil, near the village of Masara. The church is oriented to the east and shows a basilical plan, with a central nave, two side aisles defined by two rows of four mud-brick columns each, and a west return aisle.85 The apse is rectangular and is framed by two semi-columns. An arched niche is set into the sanctuary’s north and south walls, which open onto side pastophoria via small doorways.86 The results of the excavations at ʿAin es-Sabil have yet to be published. Although the dating of the church is unknown at the moment, the building seems to share some typological similarities with the Church of Trimithis and the Large East Church at Kellis, both datable to the mid-fourth century.87

1.2.5 Trimithis/Amheida

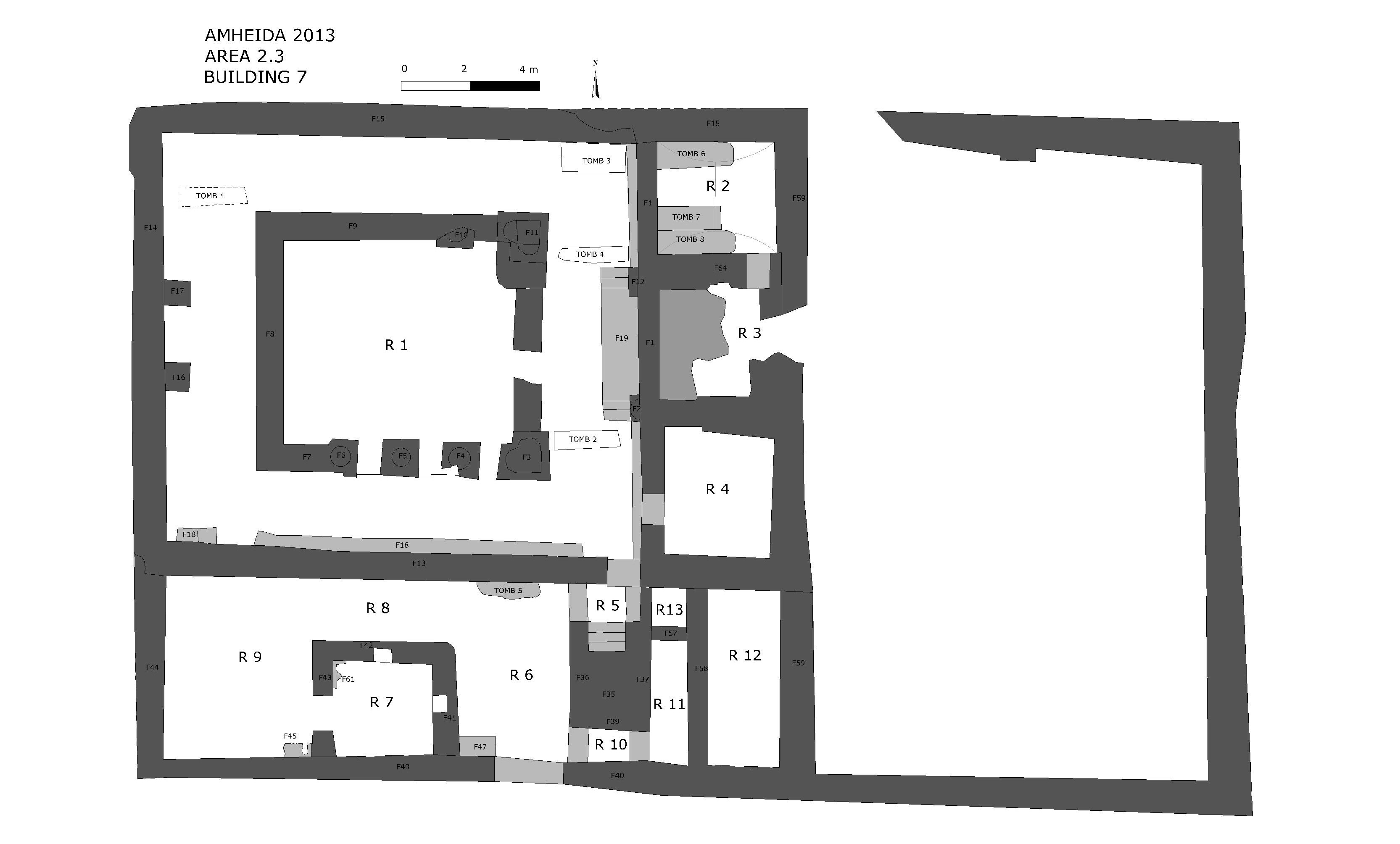

In 2012–2013, excavations carried out at Amheida (ancient Trimithis) unearthed a church complex located on a hill at the east end of the site, in a position that once granted a high degree of visibility over large portions of the city.88 The church itself,89 which is very poorly preserved due to wind erosion and/or human destruction, is oriented to the east and measures approximately 12 m north–south by 13.65 m east–west (Plate 1.8, Plate 1.9). It is of a standard basilical type, with a central nave and two side aisles defined by two rows of columns. The colonnades’ foundation walls were bonded at their east and west ends with north–south oriented foundation walls, forming a rectangle. The two colonnades were seemingly joined at their west end with a return aisle, which created a sort of ambulatory along the inner perimeter of the church. The excavation revealed only the foundation walls of the colonnades and the square bases and lowest courses of a few columns, including two heart-shaped pillars at the east end of the north and south colonnades.

Access to the church was via a large doorway located in the middle of the west wall. Two additional doorways were found in the southeast corner of the church. One of them led to the southernmost of three small spaces to the east, while the other opened onto a staircase ascending towards the south and, via the landing of the staircase, to a set of seven spaces to the south of the church.90 Some of these spaces, whose nature and functional relationship to the church are difficult to determine due to their poor condition and the lack of evidence, show signs of post-abandonment reuse.

Substantial traces of a mastaba are visible along the south wall of the church. It is likely that a similar bench ran also along the north wall of the church, although no traces are visible nowadays, due to the poor preservation of that section.

Against the east wall of the church, and in line with the west entrance along the main axis, is a well-preserved mud-brick platform, which once gave access to a raised apse (now destroyed). The apse was originally flanked by two side-chambers (also disappeared).

One of the most remarkable features recovered during the excavation of the church consists of thousands of fragments—and several large patches—of a flat ceiling, decorated with a wide array of colors and interlocked geometrical shapes forming a coffer design, which had a long history in Egypt (Plate 1.10).91

Other significant discoveries made inside the church complex included eight human burials.92 Three of them were excavated in the eastern half of the church, while a fourth tomb, located immediately outside the church along its south wall, was left unexcavated. A skeleton was also found in situ near the northwest corner of the church, although most of the burial pit had disappeared due to either human disturbances or erosion. All the other pits were intact.

No funerary goods were found associated with the excavated tombs. The orientation of the bodies was always with the heads to the west (facing east), which is quite standard for Christian burials, on the basis of comparative evidence from Christian cemeteries in the oasis; this is attested, for example, at Kellis, Deir Abu Matta, and at a site northeast of Muzawwaqa.93

Three of the eight burials were not found inside (or alongside) the church’s main body but in what turned out to be one of the most exciting findings about this building. Excavations in the area under the now-disappeared northern side-room (presumably a pastophorion) led to the discovery of an underground funerary crypt (Plate 1.11).94 It is a very well preserved space, paved with a mud floor and with only the uppermost part of the vault no longer in place. Inside it are three sealed tombs with mud-brick superstructures. The crypt opened, through a doorway in the south wall, onto a yet unexcavated space below the apse that may have been part of the same crypt.

The church had features (basilica plan with a central nave, side aisles and west return aisle, sanctuary accessible through a raised platform and flanked by service rooms) that were fairly standard in Christian architecture of late antique Egypt. Other churches in the region of the Great Oasis, such as the Large East Church at Kellis (Dakhla Oasis) and the church of Shams ed-Din (Kharga Oasis), show significant similarities to the church of Amheida.95 Clearly, the church of Amheida fits with the architectural standards that were widely adopted in the region of the Western Desert and throughout Upper Egypt in the fourth century.

As regards the nature of the liturgical practices once carried out inside the church, the evidence is scanty at best. However, what is undeniable is that the presence of burials in the church and in the crypt suggests that this building served from the very beginning (as the very existence of the crypt itself suggests), as a funerary church. The association of a church with funerary practices in the fourth century is well attested in Dakhla, for example at Deir Abu Matta and in the West Church of Kellis.

The available evidence, including ceramics, coins, and ostraka, points to an early to middle fourth-century dating for the church of Amheida/Trimithis, in line with the chronology of most other churches discovered in Dakhla thus far. The Christian community that lived in fourth-century Trimithis was undoubtedly large and thriving, with the means to choose a prime location for the construction of churches (it is expected that this church is just one of many more to be found at Amheida, particularly in light of its size and importance in Late Antiquity).

Documentary evidence on fourth-century Christianity was also gathered during the excavations at Amheida.96 Among the findings are ostraka (and a graffito) that mention typically Christian names and, in some cases, standard titles of clergymen. The most striking discovery was, however, that of a block bearing a Greek inscription and the Coptic word for “God” (pnoute) carved at a later time, possibly to replace the name Ammon that was the subject of the original inscription.97 Together with the available archaeological evidence for the existence of a church at Amheida, this written material testifies to the presence of a thriving Christian community at the site in Late Antiquity.

A fair amount of documentary material on fourth-century Christianity was found also at the site of Kellis.98 One example is a Coptic letter on papyrus fragments (P. Kell. Copt. 12), discovered during the excavation of House 2 at the site.99 Within lines 6–7, the document contains a specific reference to an individual named Titoue in relation to his trip to “the monastery to be with father Pebok.”100 This letter is quite significant, as it suggests either the presence of fourth-century monastic communities in Dakhla or links with such communities elsewhere. At the moment, no incontrovertible archaeological evidence has been found for monasteries in Dakhla, despite the survival of modern toponyms that might be related to ancient monastic establishments.101

Another letter from House 4 at Kellis (P. Kellis Copt. 123), also dated to the fourth century, contains a reference to “Father Shoei of Thaneta” (lines 16–17).102 It might be an additional reference to a monastery in Dakhla, although the reading of “Thaneta” as a Coptic word for “monastery” is not beyond doubt.103

Additional evidence on Early Christianity in Dakhla might be linked with the old mosque of El-Qasr, a Medieval town located along the northwest edge of the oasis. According to Fred Leemhuis, who leads a project for the study and preservation at the site, the tripartite structure and the east–west orientation of the mosque closely resemble the typology of the Christian basilica. Leemhuis noticed that the mihrab is not aligned with the main axis of the building, but slants awkwardly to the southeast. This might suggest that the mihrab, which had to be built facing Mecca, was a later addition to an east–west oriented building, possibly a church, that was turned into a mosque under the Ayyubids.104 A test trench was dug inside the old mosque in 2010, but it did not reveal information about the use of the building as a church.105 Nevertheless, the preliminary conclusions drawn by Leemhuis are cogent and worthy of careful consideration by scholars of Egyptian Christianity.

On the whole, the documentary and archaeological evidence for the growth and expansion of Christianity in the oasis is quite extensive and gaining an ever-increasing scholarly interest. In particular, the work carried out at Kellis/Ismant el-Kharab added significant information on several aspects regarding the early developments of Christian architecture in the Western Desert and, more broadly, in Egypt. Above all, it showed how Dakhla had embraced Christianity, together with its artistic and architectural expressions, from an early stage, which went back to at least the early fourth century CE.

The discovery of the church complex of ʿAin el-Gedida brings additional, significant evidence on the development of Christianity in the oasis, testifying to the fact that churches had become, by the fourth century, a familiar feature of not only the urban but also the rural landscape of Dakhla. Therefore, the new data will help shed light on the process of far-reaching transformations that the society of the oasis experienced, at all levels, possibly beginning under Licinius and certainly since the advent of Constantine’s rule in Egypt in late 324.106

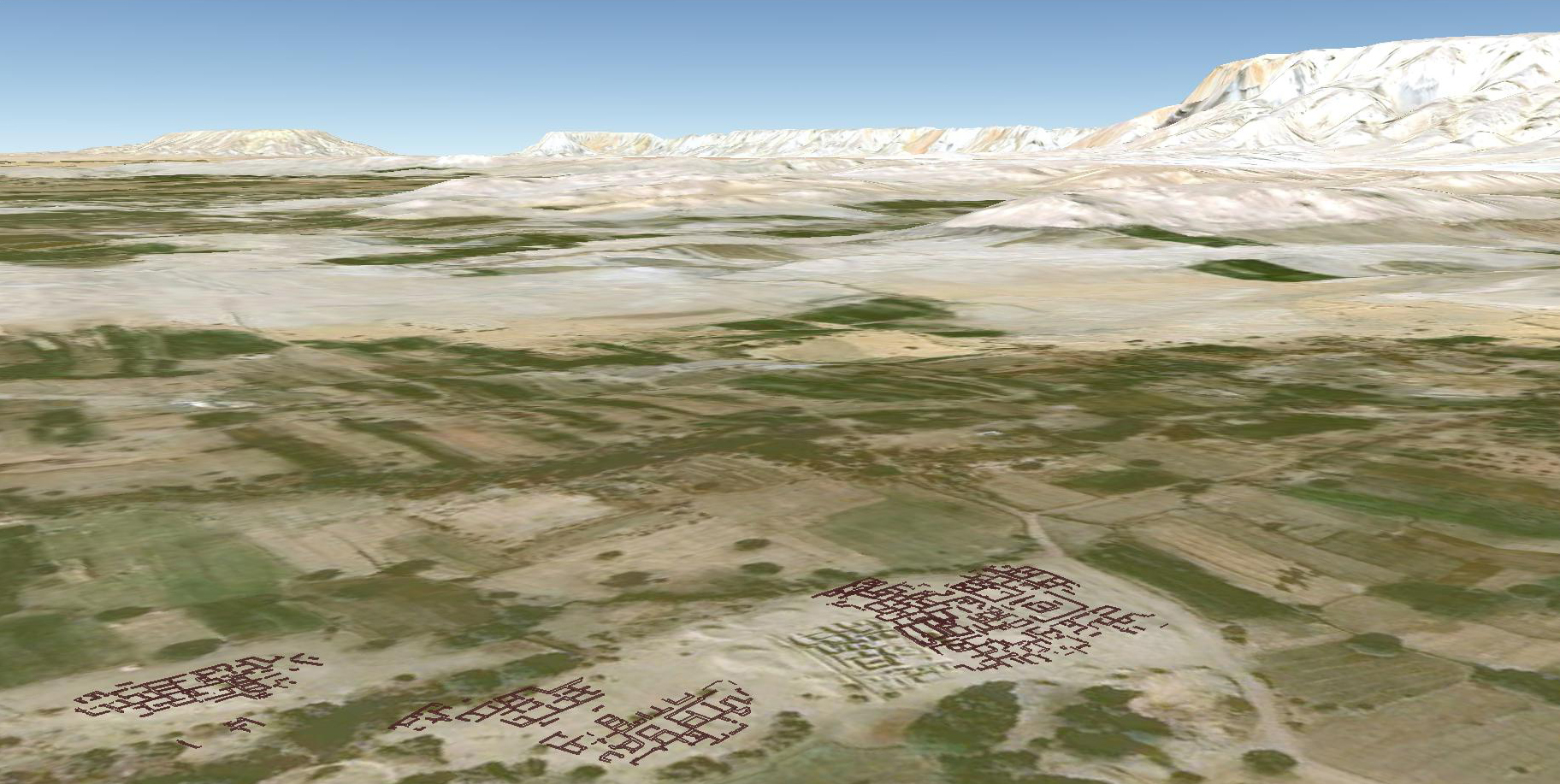

1.3 Topography of the Site

ʿAin el-Gedida is located three kilometers north of the village of Masara and a short distance to the northwest of the ancient site of Kellis (Ismant el-Kharab) (Plate 1.12). The whole site is delimited to the north by the escarpment, which dramatically divides the Dakhla Oasis from the desert plateau (Plate 1.13). A narrow strip of desert land, with two rocky mounds as its most striking topographical features, lies to the south of the escarpment. The desert is followed to the south by cultivated fields, which border with the northern edge of the settlement.

To the south, east, and west sides of the site today are mostly cultivated fields. The area is reachable through a very rough, unpaved track that leaves west of the main road leading from Dakhla to Kharga and crosses desert areas and arable land (Plate 1.14).

The area is spotted with fairly numerous trees, bushes, and palm trees, which grow thanks to the easy accessibility of water (Plate 1.15). One source lies in a sunken depression a few meters to the east of mound I;107 water is also mechanically pumped out of a modern well dug to the northwest of the site and channeled for the irrigation of the surrounding cultivated fields. A network of narrow water canals runs north–south along the west and southeastern edges of the site, but also extends—quite dangerously—into the southern sector of the archaeological area.

The toponym ʿAin el-Gedida, which means “the new spring”, points to the relative wealth of water in the area as the reason for its exploitation as cultivated land. There is a strong likelihood, although not a certainty yet, that the modern name coincides with the ancient toponym, at least on the basis of a Greek ostrakon that was found during the 2008 excavation season.108 This inscription, of a rather utilitarian content, mentions a toponym (Pmoun Berri) that is the precise Coptic correspondent of the modern name “ʿAin el-Gedida”.109 Therefore, the abundance of a precious resource like water is the key to understand why a settlement developed at ʿAin el-Gedida in antiquity and the source of its name.

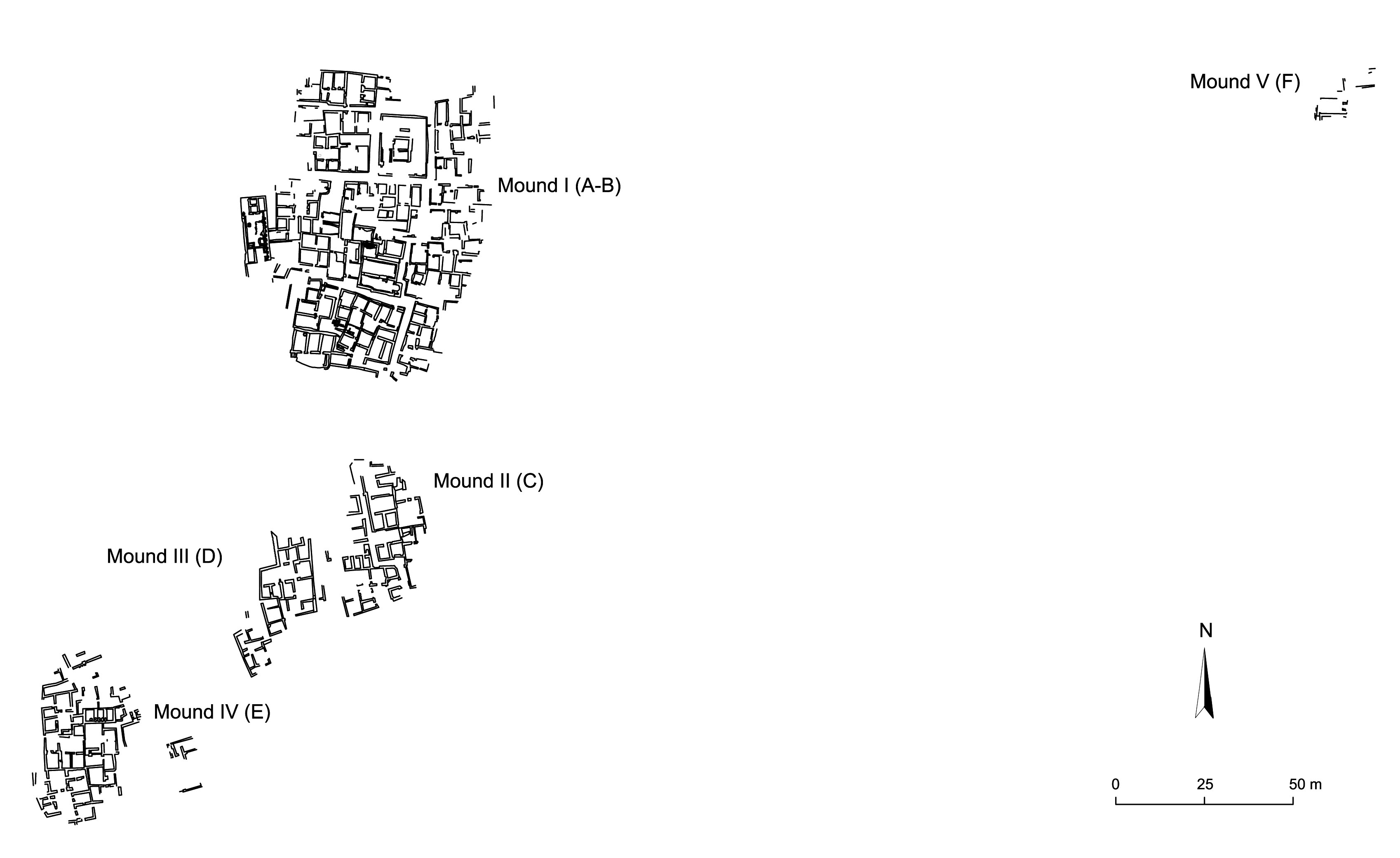

The site consists of five mounds of different sizes and heights (Plate 1.16): four of them (mounds I–IV) are relatively close to each other, while one (mound V) lies at a certain distance from the other hills.

Archaeological remains were identified on all of them, but excavation was carried out only on mound I, which lies at the center of the site at a maximum height of ca. 116 m above sea level. It is the largest of the five hills identified as part of the same settlement and the one with the largest amount of visible archaeological remains. The mound extends for about 85 m from north to south and 70 m from east to west and covers an area of about one-half hectare.110 A track runs northwest to southeast along the north edge of the hill, which borders another north–south track to the west, parallel to a low water canal and thick vegetation. A hut, used by the ghafir (guard) of the site, was built near the southeast corner of the hill.

Mound II lies about 23 m south of the main hill and is separated from it by a low east–west oriented wall, 44.2 m long, which was built by the Egyptian team in the 1990s.111 It measures 42 m from north to south and 21 m from east to west and the area of the archaeological remains is approximately 725 m².

About 48 m south of the main hill and 13 m southwest of mound II is mound III. Relatively few archaeological remains were identified above ground level, extending about 33 m north–south, 12 m east–west, and covering an area of ca. 300 m².

Mound IV lies 106 m to the southwest of the main hill of ʿAin el-Gedida. It rises about 113 m above sea level, at a slightly lower elevation than mound I. The main cluster of visible structures on the hill measures about 48.5 m from north to south and 27.8 m from east to west; it extends over an area of about 1500 m².

At a far greater distance from mound I than the three small hills to the south is mound V, which lies about 230 m to the northeast of area B, in a very disturbed context. It measures about 16 m from east to west and 11 m from north to south. The few surveyed archaeological remains extend over an area of ca. 130 m²; however, this measure is particularly approximate because of the rather poor state of preservation of the features.

It is difficult to establish the overall dimensions of the site, including the five mounds. As said above, the cultivated fields, especially to the east and west of mound I and to the south of mounds II–IV likely encroached upon a sizable portion of the ancient archaeological remains. It is therefore possible to assume that the process of agricultural exploitation of the land heavily modified the original morphology of the local environment.112 This makes it hard to assess whether the areas between and around the mounds were also zones of dense construction, forming a continuum with the five mounds, or, vice versa, if the site consisted of separate clusters of buildings on each mound. Also, the heavily disturbed context of mound V complicates the situation, making it impossible, in the absence of further archaeological investigation, to establish its outline with any degree of precision. According to the survey carried out by the Dakhleh Oasis Project in 1980, the overall extension of the settlement is three hectares.113 The CAD topographical map, which was generated using the data from the 2006–2008 survey, allowed us to calculate an overall extension of ca. 0.8 ha; since it was not possible to determine the original physical extent of the five mounds, the calculation took into account only the areas covered by the archaeological remains visible above ground.114

1.4 History of the ʿAin el-Gedida Project

In 1980, members of the Dakhleh Oasis Project carried out a preliminary survey of ʿAin el-Gedida, as part of their third season of investigation.115 The focus was on the central part of Dakhla and covered the area including the villages of Budkhulu, Rashda, Hindau, Mut, Sheikh Wali, Masara, and Ismant.116 116 sites were recorded in an area of approximately 161 square kilometres, dotted with numerous wells, springs, and water channels, the latter undated but no longer in use at the time of the survey. The archaeologists of the D.O.P. identified several ancient sites that, on the basis of a preliminary analysis of the ceramic specimens collected on the ground and from test trenches, were assigned to a rather broad chronological range called “Roman/Christian”.117 Among them was ʿAin el-Gedida, then unknown from documentary or literary sources.118 ʿAin el-Gedida appeared to the surveyors as a group of low mounds lying in the proximity of each other. Extensive archaeological remains, visible above ground, were identified on all mounds, especially on the largest hill, where 145 rooms, clustered in several complexes, were noticed. A test excavation was carried out in a sample room; this space was cleared of the windblown sand that had accumulated in it and excavated down to 2.80 m from ground level.119

The D.O.P. members assigned the site of ʿAin el-Gedida index number 31/405-N3-1, based on the site’s location within the map that included all the surveyed sites.120 No further information about the 1980 survey at ʿAin el-Gedida is available as published material, except for a brief mention of the settlement in an updated list of the archaeological sites surveyed by the D.O.P., which was published in 1999.121

In 1993, the Coptic and Islamic Inspectorate of the Supreme Council of Antiquities in Dakhla began excavation at ʿAin el-Gedida, under the direction of Mr. Ahmad Salem and Mr. Kamel Bayoumi.122 The Egyptian investigations focused on the southern half of the largest mound (area A of mound I, Pl. 2.3), where several mud-brick structures were cleared of the windblown sand and excavated, completely or in part. A very intricate complex of rooms was revealed, surrounding a large, open-air kitchen, centrally placed (A6 on the plan), and showing a multi-phased development, with the addition of clusters of rooms built against earlier ones and extending to the outer edges of the mound.

The SCA mission resumed excavation in 1994 and 1995, carrying out more investigation on the southern half of mound I and expanding the excavated area further north, where a large rectangular room (A46) was completely cleared of wind-blown sand. In order to distinguish the work carried out by the SCA mission from later excavations, all the rooms investigated by the Egyptian team on mound I between 1993 and 1995 were in our work referred to by numbers preceded by the letter A, while the rooms investigated later on mound I were given the letter prefix B.

A topographical survey, carried out eleven years after the 1995 excavation season, revealed that the SCA conducted brief, additional investigation on mound IV (area E), located to the southwest of mound I. A small rectangular room was cleared of windblown sand at the center of the low mound, but due to the lack of information and to the fact that the room is, at present, partially filled with sand, it is not known if the excavation was carried out partially or to floor level.

An intense restoration effort was carried out in the mid-1990s on several architectural features, such as walls and especially doorways, which were in danger of collapse due to their exposure to the elements and to the lack of protection provided by the sand.123

No written documentation of the work carried out at ʿAin el-Gedida in the 1990s was available to our team. Most of the architectural features excavated at that time are still extant, although filled, in large part, with wind-blown sand that accumulated in the last decade. Nine items, including five lamps, two complete clay pots, and two dull glass bracelets, were registered at the time of their discovery and then brought to the Kharga Museum.124

As mentioned above, one brief essay by Mr. Bayoumi appeared in 1998, conveying some information on the work he carried out at ʿAin el-Gedida from 1993 to 1995 and focusing on preliminary conclusions concerning the nature of the settlement, which were put forth by scholars who visited the site.125 After Bayoumi’s essay, a brief mention and description of ʿAin el-Gedida were included in Bagnall and Rathbone’s archaeological guide of Egypt published in 2004.126

In 2005, a short, preliminary visit to ʿAin el-Gedida was conducted by Olaf Kaper, Mr. Bayoumi, and the author, in order to assess the condition of the site ten years after the last SCA-led excavation season. After a few meetings, a collaborative project between the local Coptic and Islamic Inspectorate and a group of international specialists was developed, thanks to the funding provided by Columbia University and Roger Bagnall.

Archaeological investigation was resumed in the second half of January 2006 and lasted for fifteen days.127 Before scientific work started, an absolute elevation for the site was taken using a differential GPS system.128 This allowed a precise calculation of the elevations for all of the different features that were uncovered.129

A general, surface clearance of mound I was conducted in order to expose the tops of the mud-brick walls that were visible at ground level throughout the hill. The topographers recorded, with the help of a total station, all of the visible features, including the rooms excavated by the Egyptian mission in the 1990s in the southern half of the mound. More topographical work was carried out on the four smaller mounds (II–V) lying adjacent or in close proximity to mound I. The data were downloaded in Autocad and their elaboration brought to the creation of the first detailed map of the site.

Furthermore, the five mounds were surveyed with a magnetometer, which revealed six anomalies in the ground in the area south of mound I.130 Two more anomalies were identified, one north of mound I and one on mound IV. These were possibly related to the presence of features like kilns or ovens.131

Excavation was conducted in the north part of mound I in three different sectors, where the layout of several rooms, various in size and often interconnected, was clearly visible above ground. Three rooms (B1–B3) were excavated to floor level (B1) and gebel (B2–B3) in the northwest sector. The layout of rooms B1–B3 (and of the two unexcavated rooms along the north side of B1) suggests that they possibly belonged to a domestic unit. Another room (B4) was excavated to gebel southwest of rooms B1–B3. At least in its latest phase of occupation, the room was used as a dump, as suggested by the large quantity of ash, charcoal,132 organic material, broken objects, and pottery sherds found during the excavation.

After work was completed in rooms B1–B4, excavation focused on room B5, a long, rectangular space with a semicircular apse along the east short side and after investigation identified as a church. Windblown sand was removed, and a roof and wall collapse were revealed. Because of time constraints, it was decided to leave the collapse in place in order to protect the floor level until the following field season.

In addition, intensive documentation took place in area A, excavated by the Supreme Council of Antiquities in the mid-1990s. The goal was to document as many rooms as possible within that sector. The collection of information about the features uncovered in area A provided more complete knowledge about the urban topography of ʿAin el-Gedida and enabled comparative architectural analysis with the buildings newly excavated.

In addition to the large hall A46, six rooms were selected for their particular architectural interest, in order to create a representative sample.133 These rooms were easily cleared of the windblown sand that had been deposited in the last ten years, and all their architectural features were fully photographed and recorded, using standardized feature forms already adopted at Amheida.

Furthermore, an architectural survey was conducted in thirteen additional rooms in area A.134 Windblown sand was removed from all of them and detailed notes and photographs were taken.135 Most of these rooms, as well as the six mentioned above, seemed to be largely utilitarian in nature, such as magazines for the storage of food.

Before the beginning of the 2007 excavation season, two rooms previously excavated by the SCA (A6, identifiable as a large kitchen, and A7 to the northeast of A6), were fully documented and photographed. The poor conditions of preservation of the walls and of the features located inside, such as two ovens in the northwest corner of A6, required the complete backfilling of these two rooms, together with the adjacent spaces to the west and the corridor to the north. The excavation of room A25, begun in the 1990s, was completed and the documentation of its features updated.

The investigation of the fourth-century church (room B5), begun in 2006, was completed in 2007, and evidence was found of earlier phases of occupation of the site. The nave and the large hall to the north were fully documented. Further north, a complex of rooms, interconnected and spatially related to the church, was uncovered (Pl. 3.2). A narrow corridor (B7), which served as the only entrance to the church complex, led from the east into a rectangular room (B6) used, at least in its latest phase of occupation, as a kitchen and as the anteroom to the large hall and to the church to the south. Graffiti were found on the west, north, and south walls of this room, including inscriptions in Greek and in Coptic and drawings. An almost complete staircase (B8) was uncovered to the north of the anteroom, leading to a roof; its upper part was supported by a narrow vaulted passageway, which led from the anteroom into a poorly preserved room (B9) to the north, possibly used as a pantry.

Another large room (B10), not connected to the church complex and presumably functioning as a kitchen, was excavated west of the anteroom, showing clear traces of ancient damage and later repairs.

The topographers updated the 2006 overall site plan by adding the plans of the rooms that were excavated in 2007. Scalable photographs of the walls and floors of rooms B5–B9 and A46 were taken and then elaborated for photogrammetrical analysis. Sections and profiles of the church were also drawn. A microrelief of the area covering the five mounds of ʿAin el-Gedida was created, with the goal of collecting precise information about the geomorphology of the site. In addition to the fixed point created in 2006, two more survey triangulation points were set in the ground on the west and north edges of mound I. These allowed subsequent recording of topographical data to be carried out in a fashion coherent with the work done in 2007. Conventions that were set in 2007 were followed. Scalable photographs of the outer face of the eastern and southern walls of the church complex were taken and then elaborated for photogrammetric analysis. Furthermore, the planimetric and photogrammetric data of the church complex, collected in 2007 and 2008, were processed, and plates for most rooms of the complex were created. Each of them included a CAD plan of mound I, a simplified plan of the church complex, and the photogrammetric images pertaining to each room.

Permission was granted to study the nine objects that had been collected during the SCA excavations of the 1990s. A group of specialists had access to these objects in the Kharga Museum, where they were drawn, recorded, and photographed.

In 2008, excavation was resumed and focused in the area immediately to the south and to the east of the church complex.136 The main goal was to ascertain the topographical relationship of the complex with the surrounding buildings, within the topographical framework of the main hill of ʿAin el-Gedida. A long, east–west oriented passageway (B11) was excavated to the south of the church, along the north edge of area A (the zone excavated by the SCA in the 1990s). To the east of the church, a long north–south oriented street (B12), with a rather irregular layout, was investigated. It crossed another east–west passageway (B16) to the north, which formed the northern boundary of B12 and was excavated only in part in 2008. To the south, street B12 led to space B13, which was the crossroads where B11 and B12 (and another unexcavated street to the south) met. This space opened onto an unexcavated area to the east and on a room along its south side.

After the area including streets B11–B12 and space B13 was completely excavated and documented, another set of two rooms was investigated further east, i.e., rooms B14–B15, respectively identified as a storage facility and a kitchen.

Following the excavation of the area to the south and east of the church complex, further archaeological investigation was carried out along the west edge of mound I, where a large complex of eight rooms (B17–B24) was uncovered (Pl. 6.2). Its preliminary analysis pointed to different construction phases that dramatically altered the inner layout of the complex, and presumably its function(s).

The topographers surveyed the excavated rooms and updated the two plans of the archaeological site, the first showing the plan of the walls at ground level and the second depicting the overall architecture of each room. The methodological standards and graphic conventions that were set in 2007 were followed. Scalable photographs of the outer face of the eastern and southern walls of the church complex were taken and then elaborated for photogrammetric analysis. Furthermore, the planimetric and photogrammetric data of the church complex, collected in 2007 and 2008, were processed, and plates for most rooms of the complex were created. Each of them included a CAD plan of mound I, a simplified plan of the church complex, and the photogrammetric images pertaining to each room.

Several ceramic objects, complete or fragmentary, were found during the 2006–2008 excavations, as well as hundreds of small finds of different kinds and materials, among which were over one hundred fifty bronze and billon coins. All small finds were cleaned, numbered, and photographed. Written records were created for each of them and their systematic study carried out by specialists.137

1.5 Methodology of Excavation and Documentation

The archaeological excavations carried out at ʿAin el-Gedida between 2006 and 2008 were rigorously stratigraphic, based on the well-known methodologies developed by A. Carandini, E. C. Harris, and the Museum of London.138 The system followed very closely the one used at the site of Amheida and developed in its details by Paola Davoli of the Università del Salento, Italy, the archaeological director of the Amheida Project.139

Roger Bagnall held, as the project director, the scientific leadership of the entire mission and the overall responsibility for its organization and management. The author, working as the archaeological field director, was responsible for the establishment of excavation priorities and strategies, in agreement with the project director. Moreover, he was in charge of leading the archaeological operations on site each day and coordinating the processing of the data at the excavation house. A team of archaeologists was assigned the supervision of different areas (usually rooms) to be excavated. Local workmen were allocated to each area and the archaeologists ensured that their work was carried out according to the established scientific standards. The supervisors were also in charge of the documentation of the area for which they were responsible, helped by assistant supervisors.

The entire site was mapped by the topographers and divided into five mounds and areas (A to F) (Plate 1.16). As said above, the subdivision into areas was originally created in order to distinguish, within the largest mound of the site, between the sector excavated by the Egyptian archaeologists in the 1990s and the one (roughly corresponding to the north half of the hill) that was excavated ten years later by the Columbia/NYU mission. The four smaller mounds of ʿAin el-Gedida were not subdivided into more than one area each, since they had not been the object of archaeological excavation.

The area including the five mounds of ʿAin el-Gedida was divided, in the Autocad map, into a grid of 10 by 10 m squares. Due to the presence of architectural features throughout the main hill, with walls that a preliminary surface clearance had made partly visible above ground level,140 it was decided that the best way to proceed was to carry out excavation by room and not by square. Furthermore, it would have been extremely difficult, due to the very irregular morphology of the ground, in which mounds of different heights were clustered in a relatively small area, to lay out a physical grid for excavation.

The stratigraphic method adopted at ʿAin el-Gedida was based on the distinction between “Deposition Stratigraphic Units” (DSU) and “Feature Stratigraphic Units” (FSU). DSUs are three-dimensional units such as layers of sand, soil, or fillings of pits or hearths. Their borders can be natural or arbitrary on the basis of the peculiar context in which each unit was excavated. FSUs are, instead, architectural features such as walls, floors, vaults, etc.141 They can also be “negative” features, derived from the removal of DSUs, as is the case of pits or foundation trenches.

All excavated DSUs and FSUs were assigned numbers, measured, photographed, and described in detail, following common standards, on pre-printed forms; elevations were taken for all units. Several DSUs, especially artificial, man-made units, and all FSUs were drawn.

As mentioned above, a survey of the whole archaeological area was conducted with a total station, and a digital plan of the entire site of ʿAin el-Gedida was generated from the data that were collected, downloaded, and elaborated in CAD. All the archaeological remains, excavated or already visible on the five mounds, were included, as well as more recent features such as the guards’ house and contemporary tracks and irrigation canals. Additional data about the geomorphology of ʿAin el-Gedida were added with the creation of a microrelief of the area, overlapping the archaeological map. Furthermore, photogrammetric images of archaeological features, mostly of walls, were regularly taken during the excavation and then processed, in order to obtain precise and scalable plates in a relatively short amount of time.142 Some sections and profiles of walls were also drawn partly by hand, especially in cases where the archaeological features could not be photographed at an angle that would allow photogrammetric analysis.

Each day, field drawings on millimeter paper were made, at 1:50 scale, of the excavated areas. The DSUs and FSUs under investigation and the precise location of the most relevant small finds were marked on the plans, including the elevations taken by the archaeologists. In some instances, where a higher level of detail was needed, a 1:20 scale was adopted. In addition to the drawings, the archaeologists filled day notes forms, in which they recorded at length everything that occurred during each day of work on site, including basic information about DSUs, FSUs, small finds, samples, and elevations.

As mentioned above, several small finds were discovered and collected in all the rooms that were the object of archaeological investigation between 2006 and 2008. Among them were lamps, pieces of coroplastic, dull glass bracelets, beads, animal bones, and many other incomplete objects made of metal, wood, or vegetal fibers. To ensure that all finds, particularly those of a small size, were collected from each stratum, the soil and sand units were always sieved after their removal from their original context. The surface layer, contaminated and therefore lacking significant diagnostic value, was not sieved.

Depending on their state of preservation, the finds received preliminary conservation in situ before collection. The small finds were gathered in buckets labeled according to the stratigraphic unit in which they were found. Objects of special significance143 were assigned field numbers, photographed in their archaeological context, and then put in separate tagged bags. All small finds were cleaned and numbered by specialists, and the photographer took final pictures of them. Written records were created for each of the special finds.

The ceramic objects that were uncovered, in complete or fragmentary condition, during the excavation were also photographed in situ and assigned field numbers, then brought to the ceramics laboratory for cleaning, restoration, further photography, and recording. The pottery sherds, found in large quantities at ʿAin el-Gedida, were also collected in tagged bags or buckets according to their archaeological contexts (DSU or FSU) and analyzed by the ceramicists. All the fragments were scanned and quantitative analysis on forms and fabrics performed.144 After this initial gross quantification of the excavated contexts, the body sherds were normally discarded, while the diagnostic fragments were selected for drawing, photography, and further examination. The goal was to build an exhaustive paper and digital catalogue of all forms and fabrics found at ʿAin el-Gedida during the 2006–2008 excavations.145

Among the pottery sherds that were collected during the excavation of area B and the clearance of area A on mound I were twelve ostraka, ten Greek and two Coptic. They were assigned field numbers and photographed in situ; then, they were cleaned, recorded, and photographed. Their analysis was carried out by Roger Bagnall and Dorota Dzierzbicka.146

Over one hundred fifty coins were found on mound I at ʿAin el-Gedida between 2006 and 2008.147 Unfortunately, several were in a very poor state of preservation. Most of them were assigned field numbers and photographed in situ.148 They were cleaned in the small finds laboratory by experts, then weighed, photographed, and recorded. Even after cleaning, many remained illegible. A small finds form was filled out for each coin. The detailed analysis of all numismatic evidence from ʿAin el-Gedida was carried out by David Ratzan, who compiled a catalogue and report.149

Several of the objects (ceramic vessels, lamps, and coins among others) uncovered during the 2006–2008 excavations were registered by representatives of the local Coptic and Islamic Inspectorate of the Supreme Council of Antiquities. They are currently in SCA storage facilities in Dakhla150 and accessible by permit.

Soil samples, including ash and sand rich in organic material, were collected from secure contexts for archaeobotanical analysis.151 Some materials, such as fragments of unfired pottery and plaster, were also kept for technical analysis, and forms with basic information for each sample were filled. The goal behind the collection of the samples was to obtain, from their analysis, additional information on patterns of food consumption at the site in Late Antiquity.152

Three seasons of excavation, carried out largely in the northern half of mound I, and also the survey of several rooms in area A, excavated in the 1990s but at that time left undocumented, led to a substantial amount of data, consisting of written forms, plans, drawings, and photographs. It was decided to leave the documentation in hard format in Egypt until the completion of all excavation and documentation work on site. However, it was necessary to find a way for all specialists involved in the project to make use of the data also outside of Egypt. Furthermore, the large bulk of information had to be organized in a fashion so that it would be of easy access to them and facilitate searches and comparisons at different levels. Therefore, a database was developed by Bruno Bazzani using Microsoft Access software, mirroring the one already in use at the site of Amheida. Digital forms were created using the same fields included in all paper forms, which were filled during the excavation and documentation process on site. To reduce the possibility of loss of information or mistakes in the data-entering process, all paper forms were scanned and linked to the corresponding digital forms.

All photographs, already in digital format, were added to the database and linked to the digital forms associated with each specific image. Also, all lists, day drawings, and day-notes were scanned and included in the database, together with all the digital plans, the microrelief of the site, the photogrammetric images, and all excavation reports.

As a result, the database allowed for fast and straightforward access to the documentation and for effective cross-reference searches of information according to diverse parameters. For example, tools were created to search the archaeological data either by year, or area, or room, etc, therefore contributing substantially to an effective processing of the data by the specialists. To further facilitate access to the documentation by all members of the ʿAin el-Gedida mission, and eventually by the general public, it was decided to make the database available on-line as an open-access resource, which will facilitate the reader’s in-depth study of the site and supplement the inevitably limited detail presented in this report.153

1.6 Conservation Strategies for Structures in situ

The poor condition of many rooms excavated and surveyed from 2006 to 2008 raised the question of conservation at ʿAin el-Gedida. Several problems must be faced when dealing with fragile materials such as mud bricks and mud or gypsum plaster. Once the archaeological remains are completely exposed, no longer protected by windblown sand, they become subject to the dangers of the harsh natural environment (including strong winds, sunlight, sand dunes, and salinization) and face physical, chemical, and biological deterioration.154 New chemicals and techniques are regularly developed and tested, but they are often very expensive and not always effective under any conditions. In light of the specific conservation issues faced at ʿAin el-Gedida, backfill following complete documentation was selected as the most suitable and cost-effective option.155 Particular attention was paid to features that were more in danger of collapse or damage,156 such as, within the church complex, the staircase (B8) and doorways without lintels in rooms B6, B9, and B10. Furthermore, the graffiti on the west and north walls of room B6 were protected with mud-brick screens placed at a short distance in front of them, with the space in between filled with clean sand. In 2008, the church (rooms B5), the large hall (room A46), and rooms B9–B10 were completely backfilled with clean sand, and partial backfilling was carried out in all other excavated rooms. In area A, several architectural features were the object of partial restoration by the Egyptian mission in the mid-1990s. The rooms whose full documentation was carried out in 2006 and 2007 were either partially or completely backfilled.

1.7 Notes

Detailed information on the geology and geomorphology, but also on the palaeobotany and palaeozoology of the Dakhla Oasis, is available in Kleindienst et al. 1999. See also Mills 1999: 171.↩︎

Especially in the months from March to June: see Kleindienst et al. 1999: 3.↩︎

Vivian 2008: 180–81. See also Giddy 1987: 10–11.↩︎

From west to east: Bab el-Qasmund, Naqb Asmant, Naqb Balat, Naqb Tineida, Naqb Rumi, Naqb Shyshini: see Vivian 2008: 180.↩︎

The particular type of sandstone found in Dakhla is described in detail in Schild and Wendorf 1977: 10. On the underground water and its possible sources, see Giddy 1987: 29–31.↩︎

Wells are considered a source of considerable wealth in the oasis: see Mills 1999: 177. On phreatic layers beneath the Western Desert, see Ball 1927a, Ball 1927b, Hellström 1940, Murray 1952.↩︎

On the irrigation systems used in Dakhla in antiquity and modern times, see Mills 1999: 173.↩︎

Arabic plural: qanawat.↩︎

Youssef 2012. These investigations were carried out under the auspices of the Egyptian Ministry of State for Antiquities.↩︎

Possibly linked to the different geomorphology of the two oases and Dakhla’s more abundant water resources: cf. Bagnall and Rathbone 2004: 262. On qanats in Kharga, see, among others, Grimal 1995: 572–74 and Wuttmann 2001.↩︎

Thanks to the work of R. Schild and F. Wendorf (see their 1977 volume).↩︎

Giddy 1987: 51–52.↩︎

Dates, olives, and wine were among the specialized products of Dakhla and the other oases of the Western Desert in Roman times: see Kaper and Wendrich 1998: 2. According to Giddy 1987: 5, it is possible that the Romans were also interested in the extraction of alum.↩︎

Cf. P Kellis IV 73.↩︎

As testified to by the available archaeological and documentary evidence: see Bagnall and Rathbone 2004 [pp. 249; 262].↩︎

Boozer 2007: 65–66. On military outposts in Kharga, see, among others, Reddé 1999 and Rossi 2012. On the remains of the Roman castrum in El-Qasr (Dakhla), see Kucera 2012.↩︎

Bagnall 2015: 7. See Hope 2001 on the occupational history of Kellis. There is no consensus among scholars on the reasons for the decline in the local population and the abandonment of sites in Dakhla (and neighboring oases) during the fifth century. Diminished access to water may have likely caused (or contributed to) the abandonment of parts of sites in the region: cf. Kaper 2012: 718.↩︎

See Starkey and Starkey 2001 and Kleindienst et al. 1999: 7–8.↩︎

See Beadnell 1901; Vivian 2008: 429 (and more extensively in the 2000 edition of the same volume: 39–42).↩︎

Thurston 2003: 17–22.↩︎

See the D.O.P website: http://dakhlehoasisproject.com.↩︎

The discussion, included in this section, on the churches of Kellis, Deir Abu Matta, Deir el-Molouk, ʿAin es-Sabil, and Amheida/Trimithis appeared in an earlier version in Bagnall 2015: see Aravecchia 2015a, Aravecchia 2015b.↩︎

Such a connection will be established in the following sections, particularly Chapter 3, Chapter 5, and Chapter 7.↩︎

On the beginnings of Christianity in Egypt, see, among others, Bowman 1996: 190–202, Wipszycka 1996, and Davis 2004. On Early Christianity and ecclesiastical institutions in Egypt, see Wipszycka 1997; Wipszycka 2007.↩︎

For an introduction to Kharga, see Vivian 2008: 117–72 and Bagnall 2004: 249–61.↩︎

Among the most significant monuments of the Christian era in Kharga (and with the most dramatic visual impact on the natural landscape) are the cemetery of Bagawat Fakhry 1951; Cipriano 2008 and Deir Mustafa Kashef Müller-Wiener 1963.↩︎

Winlock 1936: 60–61.↩︎

119 “Byzantine” sites are listed in Churcher and Mills 1999: 263–64.↩︎

Although not necessarily occupied only in that period.↩︎

“Late Antique” is intended here as broadly overlapping, in chronological terms, with “Byzantine” (as used in the D.O.P. survey).↩︎

Bowen 2003a: 168–71; see also Bowen 2008, Bowen 2009.↩︎

While the evidence for earlier times is somewhat scantier: see Bagnall 1993: 278–80.↩︎

Bagnall 1993: 261–68.↩︎

The following discussion of the churches of Kellis is based on Bowen 2002a and Bowen 2003b.↩︎

Knudstad and Frey 1999: 189, 201, 205.↩︎

There is a second door in this wall, opening onto a long, narrow room possibly used as a magazine: see Bowen 2002a: 77.↩︎

The archaeologists found the remains of mud-brick bins, donkey hooves, and straw in one of the rooms, which might have been used to keep animals: see Bowen 2002a: 78.↩︎

For a different view on the nature of the complex as administrative, see Bowen 2002a: 78. On another church, recently discovered at Amheida/Trimithis, that was used as a funerary complex, see further below in this section; see also Aravecchia 2015a and Aravecchia et al. 2015: 138.↩︎

No ceramics with diagnostic value were retrieved in the fill of the complex; see Bowen 2002a: 83.↩︎

Roger Bagnall (personal communication, February 2011). See also Aravecchia 2015b: 138.↩︎

Whose exact shape and size are unknown.↩︎

See Knudstad and Frey 1999: 205–6 and Bowen 2003b.↩︎

Bowen 2003b: 158. According to her report, the west doorway was created by removing part of the original wall, and the central one was narrowed.↩︎

For a detailed discussion of the church of ʿAin el-Gedida in relation to the Small East Church at Kellis, see section Section 5.3.1 in this volume.↩︎

Bowen 2003b: 162.↩︎

Bowen 2003b: 164.↩︎

Bowen 2002a: 65–75. According to the report of the excavator, the church possibly had a flat roof.↩︎

Grossmann identified the feature as an ambo (Bowen 2002a: 73). On the west return aisle in Upper Egyptian churches, see Grossmann 2007: 104–7.↩︎

The bema of Kellis’ Large East Church is very similar to that of the recently excavated church of Amheida/Trimithis, also in Dakhla and sharing a similar chronology.↩︎

Bowen 2002a: 81–83. The ceramic evidence found between the floor and the foundation level was dated to the first to third centuries CE.↩︎

For a discussion on the chronology of the church of ʿAin el-Gedida, see Section 5.1 and Section 7.1 in this volume.↩︎

In addition to the churches discussed in this section, Bowen recently reported on findings related to an Early Christian church at the site of Mut, the largest city of Dakhla in antiquity: see Bowen 2012a and Bowen 2012b: 434, n. 4.↩︎

D.O.P. number 31/405-M6-1.↩︎

The information about the church is drawn mostly from Mills 1981: 184–85, pls. X–XI and Grossmann 2002a: 566–67, plan 181.↩︎

Although its exact placement is not marked on the available plans.↩︎

D.O.P. number 32/405-A7-1.↩︎

Winlock 1936: 24, pls. 12–13.↩︎

Grossmann 2002a, plan 180. Little archaeological evidence of the two east–west colonnades is available, and only in the western section of the church.↩︎

Bowen (2008a: 11) noted how this doorway, ca. 84 cm wide, might have been too narrow to function as the main entrance. The latter may have been placed along the west wall.↩︎

Bowen 2012b: 448–49.↩︎

Bowen 2008a: 8.↩︎

According to Vivian 2008: 199, the site is also known as Deir al-Saba Banat (“Monastery of the Seven Virgins”).↩︎

Bowen 2012b: 449.↩︎

Bowen 2012b: 449.↩︎

See Grossmann 2002a: 566, according to whom the church was built right before the Arab conquest.↩︎

The church’s measurements are ca. 9.4 m north–south by 10.6 m east–west. The entire complex measures roughly 17 by 26 m.↩︎

Information based on a personal visit to the site (before a full excavation of the church was carried out). Additional information was provided by Roger Bagnall (personal communication, 2014).↩︎

Some ostraka, found in a complex adjoining the church, were analyzed by Roger Bagnall and Rodney Ast and dated to the 360s, possibly the last occupational phase of the building (Ast and Bagnall 2016).↩︎

The excavations, under the author’s field direction, were part of a larger project directed by Roger Bagnall and under the field direction of Paola Davoli. For a recent introduction to the finds from these excavations, see Bagnall 2015.↩︎

A similar layout, with rooms lined along the south wall of a church, is attested elsewhere in Egypt; one geographically close parallel is that of the Large East Church at Kellis (Bowen 2002a: 66, 71).↩︎

An earlier example of this coffer design is attested in Dakhla, where Colin Hope excavated a Roman villa, dated to the second century CE, at Kellis. The investigation revealed extensive traces of a collapsed ceiling with a very similar decoration (Hope and Whitehouse 2006: 321). A chronologically closer parallel was found in a family chapel at the Christian necropolis of Bagawat, in the neighboring Kharga Oasis: see Fakhry 1951: 83 (pl. VI: reconstruction). For more recent illustrations, see Zibawi 2003: 24 (fig. 14); Zibawi 2005: 25, 30–31.↩︎

On the analysis carried out on four bodies from the church by physical anthropologists Tosha Dupras and Lana Williams, see Aravecchia et al. 2015.↩︎

Aravecchia et al. 2015: 24–26.↩︎

See Bowen 2002a: 65–75 on the Large East Church at Kellis and Bonnet 2004 on the church of Shams ed-Din.↩︎

See Bagnall and Cribiore 2012 and 2015.↩︎

Bagnall and Cribiore 2015: 131–33.↩︎

Not all of them were, in fact, Orthodox Christian. Indeed, written sources exist that testify to a strong Manichaean presence in the region during the fourth century. On Manichaeism in Dakhla, see three essays by Gardner 1997a, Gardner 1997b, Gardner 2000.↩︎

Gardner, Alcock, and Funk 1999: 131–34.↩︎

Such as Deir el-Molouk and Deir Abu Matta. Winlock 1936: 24 mentions other toponyms (recorded by earlier visitors to the oasis, such as Beadnell and Drovetti) as evidence for the existence of Christian communities in the oasis during Late Antiquity: a well to the south of Qalamun, called ʿAin el-Nasrani (“the Christian’s spring”), and two other sites in the same area, called El-Selib (“The Cross”) and Buyut el-Nasara (“Houses of the Christians”). G. Wagner argued that the village of Tineida, located at the east end of the oasis, derived its name from the Coptic word for “monastery”: see Wagner 1987: 196.↩︎